A Maya ambassador’s grave reveals his surprisingly difficult life

The bones of a Maya ambassador suggest a life of privilege but not necessarily comfort and ease, even though he was a high-ranking official born into a powerful family. His skeleton also finishes the story started in the hieroglyphic inscriptions on his tomb, revealing his greatest achievement and his fall from power after political winds shifted.

Look upon my works, ye mighty, and despair

In late 726 CE, diplomat Apoch’Waal’s fortunes were on the rise. He had inherited his father’s position as a lakam, or standard-bearer: a diplomatic emissary for the King of Calakmul. As a sign of his office, Apoch’Waal carried a banner on a pole while he walked hundreds of miles to broker alliances between the most powerful dynasties in the Maya world. When he spoke or smiled, the jade and pyrite inlays in his front teeth also revealed his high status.

That summer, Apoch’Waal took up his banner and set out on a 560-kilometer trek to Copán, in modern-day Honduras, to forge ties between the king of Copán and his own king. The successful alliance between kings was a high point in Apoch’Waal’s career, and he commemorated it a few months later by building a small ceremonial platform and temple for himself in his hometown of El Palmar, near Calakmul.

The platform served as a stage where priests would have publicly performed rituals, and its presence would have boosted Apoch’Waal’s status even higher. The nearby temple, in fact, would serve as his tomb when he died. On the stairs leading up to the ritual stage, Apoch’Waal commissioned hieroglyphic inscriptions telling the tale of his diplomatic success and boasting of his prowess as a ballplayer.

Apoch’Waal, standard-bearer of the king of Calakmul, seemed to be on a meteoric rise in 726 CE. But that’s the thing about meteors: they fall. The stairway to the diplomat’s ritual stage tells of his rise, but his bones, buried nearby in a modest grave, tell of the fall.

Living (and dying) in reduced circumstances

Archaeologists Jessica Cerezo-Román and Kenichiro Tsukamoto were surprised when they unearthed Apoch’Waal’s grave beneath the floor of his temple at El Palmar (now located in Mexico near the borders with both Belize and Guatemala). The bones of a middle-aged man, between 30 and 50 years old when he died, lay exactly where the owner of the platform should have been buried, but the grave itself was surprisingly modest.

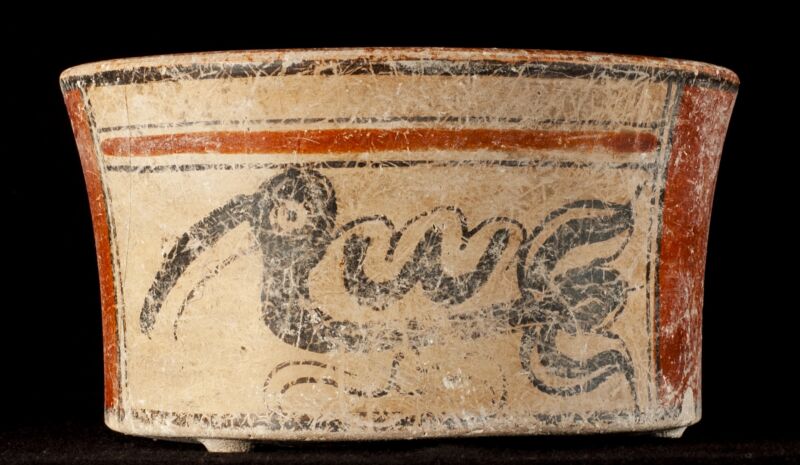

Building the platform had been an incredibly expensive and showy way for Apoch’Waal to toot his own horn, and it’s something only a wealthy, powerful person would have been able to do. Archaeologists would expect someone like that to be buried with a trove of jewelry and other grave goods, but Apoch’Waal had been buried with just two decorated clay pots. When the once-renowned diplomat died, he could still claim the platform and temple but, evidently, not much else.

The alliance between the Maya kings of Calakmul and Copán was no small thing, but it didn’t last. Within a few years, rival dynasties had knocked both kings from their thrones. Copán’s king literally lost his head, and political upheaval shook the region for years afterward. The political instability brought an economic downturn with it, especially for smaller communities like El Palmar.

People like Apoch’Waal, whose status and wealth had been linked to the now-deposed ruler of Calakmul, endured a change in personal fortunes as well.

He had lost several of his lower left teeth to gum disease, and his lower jaw showed signs of an abscess in a right premolar. All of that meant he probably spent his final years with constant toothaches and restricted to a diet of soft foods. Adding to the diplomat’s dental woes, he’d lost one of the gemstone inlays that marked him as a member of Maya high society.

Probably around the time he inherited the standard-bearer title from his father, Apoch’Waal’s upper front teeth (incisors and canines) had been drilled and fitted with inlays of jade and pyrite, which was common for high-ranking Maya men. But sometime before he died, the inlay fell out of Apoch’Waal’s right canine, and he apparently didn’t have the means to replace it; dental plaque filled the hole and hardened into calculus, which tells archaeologists that the gap formed long before death. The missing gemstone would have been a visible sign that Apoch’Waal had fallen on hard times.

Not an easy life, but probably an interesting one

But if Apoch’Waal’s life was once much more glorious, his skeleton suggests that it was never exactly easy. By the time he died, the standard-bearer’s bones showed signs of arthritis in his hands, right elbow, left knee and ankle, and both feet. That suggests that his title wasn’t just honorary; that’s the kind of wear and tear you’d expect on the bones of someone who literally carried a banner on a pole across hundreds of kilometers of uneven terrain. Diplomacy clearly wasn’t a desk job during the Maya Late Classic Period (600 to 800 CE).

“Although these elites are depicted on polychrome vessels and carved monuments, little is known about their life experiences and mortuary practices,” wrote Cerezo-Román and Tsukamoto.

Even as a child, Apoch’Waal’s bones suggest, he suffered despite his high social standing. His father descended from a line of lakam, and his mother was also of noble birth, but the thin bones of his skull show signs of a condition called porotic hyperostosis, which is usually the body’s response to childhood illness or malnutrition. The spongy inner layers of bone swell up, while the usually hard, solid outer layer becomes thinner and more porous.

One arm also showed signs of healed inflammation, which could have been caused by scurvy (a vitamin C deficiency), rickets (a vitamin D deficiency), or an infection. Archaeologists would expect to find such evidence of malnutrition and sickness in one of Apoch’Waal’s poorer neighbors, not in a diplomat of noble birth. It suggests that, even for social and political elites, life during the Late Classic Period was hard and uncertain.

Latin American Antiquity, 2021 DOI: 10.1017/laq.2020.96 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1750214