A physicist studied Ben Franklin’s clever tricks to foil currency counterfeiters

Most people associate nuclear physics with the atomic bomb or nuclear power plants, and those associations are often negative. Michael Wiescher, a nuclear physicist at the University of Notre Dame, wants to change that perception by applying his expertise—and some of his sophisticated imaging hardware—to research that bridges science, history, and culture. His work in this area has included collaborations to analyze a rare medieval manuscript and unearth currency fraud and forgery throughout history, most notably in ancient Rome and Colonial America. He recently described those efforts at a virtual meeting of the American Physical Society’s Division of Nuclear Physics.

Much of this work was conducted in conjunction with undergraduate students in physics, chemistry, art restoration, history, and anthropology as part of a course Wiescher teaches at Notre Dame on physics-based methods and techniques in art and archaeology. In the process, students can get certified as operators of a broad range of advanced physics-based instruments and techniques. These include Raman spectrometers, transmission electron microscopes (TEM), a 3MV tandem accelerator, handheld X-ray fluorescence (XRF) scanners, micro-XRF scanners, and X-ray diffractometers, among others.

The course covers such topics as nondestructive analysis of the paintings of Vermeer and the Archimedes palimpsest; tracking the inks used by medieval scribes for illuminated manuscripts; whether the Vinland map is real or a forgery (it was recently conclusively shown to be fake); using studies of the Shroud of Turin to discuss uncertainties in carbon dating; and reviewing how Luis Alvarez once used cosmic rays to search for hidden chambers in Egyptian pyramids in the 1960s.

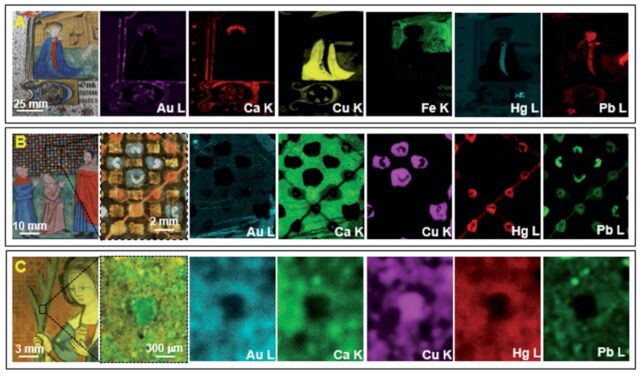

One of Wiescher’s projects was a 2016 analysis of a rare 15th-century illuminated Breton manuscript. Wiescher and his collaborators combined micro-XRF elemental mapping with Raman spectroscopy to gain deeper insight into how the manuscript’s illustrations were prepared and the particular pigments that were used. The first technique reveals the elements present as well as individual pigment particles and how they are distributed across regions of interest. The latter is ideal for analyzing select areas to reveal the molecular compositions of the pigments. Based on their findings, Wiescher and his co-authors concluded that the Breton manuscript was likely the work of a single artisan or perhaps a small number of artisans working from a single palette.

Wiescher turned his attention to Roman denarii in 2019. The Roman silver denarius was the backbone currency of the Roman Empire between 200 BCE and 300 CE, according to Wiescher. During Nero’s reign, the coins were required to be 92.5 percent silver, in order to protect the currency against inflation and devaluation. Despite the emperor’s reputation for tyranny and debauchery, “Nero was a one of the most fiscally responsible of his progenitors and successors, sticking to the laws in the way of having the coins minted,” said Wiescher.

But the analysis of coins from 250 BCE to 350 BCE showed declining percentages of silver. According to Wiescher, the Roman mints gradually debased the denarius, deliberately, to increase their profits and make it easier to finance ongoing wars in the empire. The mints relied on certain metallurgical techniques to hide the lower percentages of silver to keep inflation at bay. By 295 CE, the silver content was just about 5 percent.

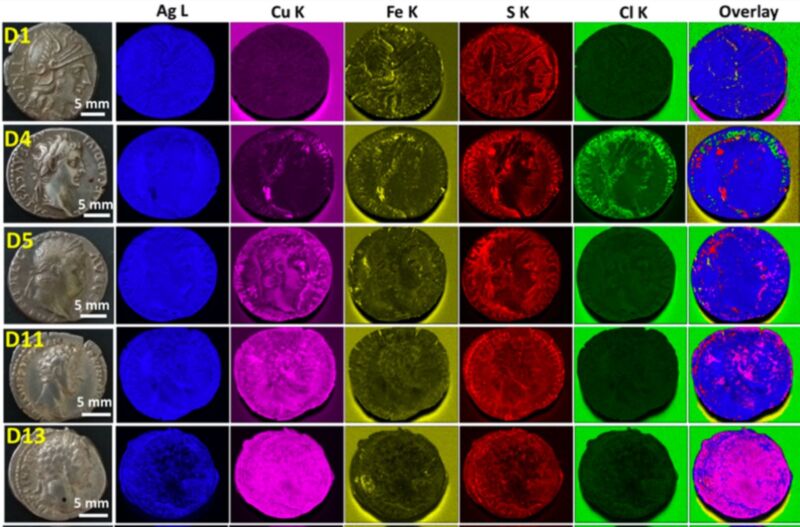

Wiescher and his students combined XRF scaling with PIXE mapping of the coins to test the currency’s quality and learn more about the production techniques. They also used electron spectroscopy to measure the silver content of each coin and how the impurities were distributed. Their analysis revealed that most of the coins are composed of silver and copper and that sulfur and iron impurities led to corrosion in some of them.

Merchants would typically test any coins proffered as payment by biting on them, since they should be able taste the silver. This would reveal any attempt to cut corners. “So the Romans invented a number of interesting technologies in metallurgy to hide [that debasement],” said Wiescher. For instance, throwing a mixed silver/copper coin into liquid mercury will cause the silver to dissolve and flow around the coin. “Then you remove the coin from the mercury bath and heat it up to drive the mercury out,” said Wiescher. This gives you a silver coin with a copper core, capable of passing the bite test.

The same trick of replacing some of the silver in coins with copper showed up again thousands of years later in Spain’s Latin American colonies. Wiescher analyzed 91 silver rials dated between the 16th and 18th centuries, from Mexico and Potosi, Bolivia. Between 1645-1648, the silver content dropped from 92.5 percent sterling to just 70-80 percent; the rest was a copper admixture. When this was discovered in the 17th century, the silver market in Spain crashed and the coins were devalued, with devastating effects on the colonial Spanish economy, per Wiescher.

Some of that silver from Spain and Mexico eventually made its way to the early American colonies. The colonies initially adopted the bartering system of the Native Americans, trading furs and strings of decorative shells known as wampum, as well as crops and imported manufactured items like nails. But the Boston Mint used Spanish silver between 1653 and 1686 for minting coins, once again adding a little copper or iron to increase their profits.

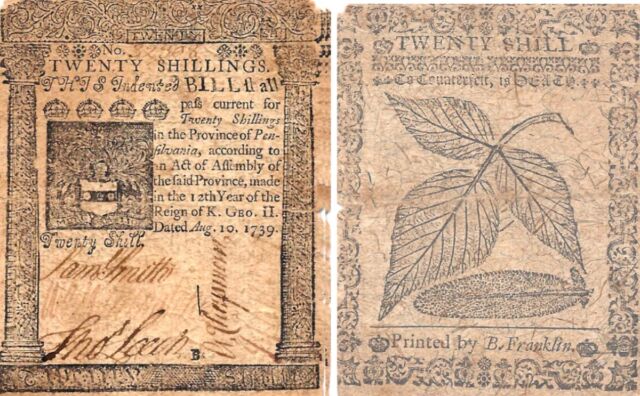

The first paper money appeared in 1690, when the Massachusetts Bay Colony printed paper currency to pay soldiers to fight campaigns against the French in Canada. The other colonies soon followed suit, although there was no uniform system of value for any of the currency. To combat the inevitable counterfeiters, government printers sometimes made indentations in the cut of the bill, which would be matched to government records to redeem the bills for coins. But this method wasn’t ideal, since paper currency was prone to damage.

In light of that early history, it’s appropriate that Benjamin Franklin is featured on the US 50-cent piece and 100-dollar bill, given his efforts to promote printed currency and combat forgeries in Colonial America. By the time he was 23, Franklin was a successful newspaper editor and printer in Philadelphia, publishing The Pennsylvania Gazette and eventually becoming rich as the pseudonymous author of Poor Richard’s Almanack. He was a strong advocate of paper currency from the start.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1804790