A year on: the highs and lows of a new engineering education system

One of the last times I wrote anything for Ars Technica, I excitedly detailed our new electrical engineering curriculum. We were starting a pilot in February and I promised to write a follow up at the end of the academic year, which was in July. To be honest, I was so exhausted by the semester that I simply could not bring myself to write about it over the summer holiday.

Now, as we exit the Christmas holiday, I finally feel able to paint a picture. It’s not all bright colors and beautiful landscapes, but the view looks promising.

For those of you who don’t remember the earlier piece, a summary: we switched from a traditional course-based curriculum to a project-based curriculum, where the students had to choose how to show that they could use their electrical engineering knowledge. The philosophy is that being able to apply knowledge and skills in the right context is a good signal that someone understands what they’ve learned. That means we have to set the right context and provide the students the opportunity to acquire the right knowledge and skills.

We are, as I said early, not there yet. But the progress is now visible.

If I were to summarize what we have learned in the past year: good educational tools really matter, global communication with students has to be effective, and teachers have to subordinate their lessons to the project.

The tools

Prior to this new approach to teaching, I have gone through various iterations. I’ve tried being that teacher with a million slides per lesson. I’ve tried being the chalk and talk teacher with no slides. I’ve tried being the teacher with bells-and-whistles interactive lesson material. In a traditional setup with a focus on direct instruction, the tools are up to the individual teacher.

In an integrated curriculum, where the students are expected to take the initiative and need timely and good feedback, the tools really really matter and cannot always be left up to the individual teacher. When we started in February, our current learning management system couldn’t easily support us. A modern learning management system was promised and I managed to get us in the pilot for its roll out… but it wasn’t going to be available until the middle of the semester. We still didn’t have a good tool to support the students, who needed to gather what they’ve done into what we termed portfolios. And, we didn’t have a good way to formalize the feedback given to students.

In the end, the first half of the semester ended up based on Microsoft Teams. Teams is Sharepoint in a suit and bowtie that hides the missing arm, broken knee, and brain damage. The students’ portfolios were basically folders with permissions manually set to restrict access. Channels were used to store relevant learning material, exercises, and project information. No one, not even the teachers, knew where to find anything.

Moving to Canvas, our new learning management system, improved matters. Since that was also new to us, however, we could not make the best use of it. After half of one semester, the one clear need was for some good tools and the ability to make consistent use of them.

The teachers

The teachers were caught out by the new style of teaching. The idea is that the students should take more responsibility for their education. Student choice and freedom should be expressed in their project and the sort of evidence of competence they delivered via that project. This also means that students have the choice of attending lessons and practicals—it is their education, and if they don’t want to show up to class, that is their choice. This was a huge cultural change for our teachers, and they were constantly asking each other how they could enforce student attendance. And I was constantly having to tell them that they shouldn’t even try to.

Some of the teachers took student choice to mean that the student should get choices in everything. For example, one teacher simply set some goals for an assignment (what the assignment should show). The students responded to that by producing individualized assignments—and very good results too. But then the teacher was faced with a class of individualized assignments to grade: a task that takes quite a bit of time. That would have been okay, if that was the only assignment and was included in the portfolio (which it could have been). But it wasn’t the only assignment, and the students did not realize that they could and should use the assignments as evidence. So, the teacher was stuck with much more grading than he should have had to do, which was then wasted because of poor communication.

Other teachers simply continued with their old routine of assignments, with the expectation that students would provide feedback to each other on their assignments. But, with no way to enforce feedback, he found himself giving feedback on every assignment from every student, which was also not the intention.

The teachers also found it incredibly difficult to work with the student projects. Since each student was working on something different, the teachers were never sure what was relevant or not to the students… and didn’t really ask either.

On the positive side, the students came up with some pretty good ideas about what they wanted to build. And even scaling the ideas to something they could do within the time allowed and the knowledge that they could build in that time was also not so difficult. But the teachers were entirely unprepared for the demands that that would create. For instance, the students all needed to know about connecting things like accelerometers to a microprocessor early in the project. But the software teacher was building up from variables, control statements etc… (using a compiled language) and that left very little time for the students to figure out how to read data from their sensors.

In the end, individual students did deliver partial results for their projects, but a lot simply did not know how to deliver evidence of their knowledge, or even what counted as evidence.

The students

The students suffered from many doubts, and were very confused about what could or could not be used as evidence. Poor communication was at the root of this. Thanks to poor tools, communicating with the students and providing an easy and clear way to build up a portfolio was really difficult.

The promised feedback was very limited. The group mentors were not able to keep track of what the students were up to, and the individual teachers were not able to translate their classroom contact into feedback for either assignments or the student project work. This left the students swimming in a sea of uncertainty.

Even knowing when to work was uncertain. We divided the day: morning was lessons and afternoon was project work and self-study. But, the project work and self-study was not in the student roster. The school Corona rules said that students were only allowed at school for project work and practicals, but since it wasn’t in the roster, the students were not sure if they were allowed at school. End result: much less actual project time than expected.

Version 2.0

We started the new approach with a small group of 15 students. The September cohort would be about 100 students, so we needed to make some changes. Since we had shown that none of the teachers were prepared to cope with students that had individualized projects, we created a single “kit” project for the first half of the semester. In that project, the students could demonstrate about 90 percent of what was expected for first half of the semester.

Again, there was a valley of uncertainty. The first task for the students was to attempt to figure out what they needed to do to complete the project. After about two and a half weeks of struggling, we gave them a project introduction. Every student attended, and every student sprang into action directly afterwards. The teachers were horrified when I said that this was exactly what I wanted (although the introduction was a week too late): we give the students the chance to progress on their own, and then provided a lesson to help them over a barrier.

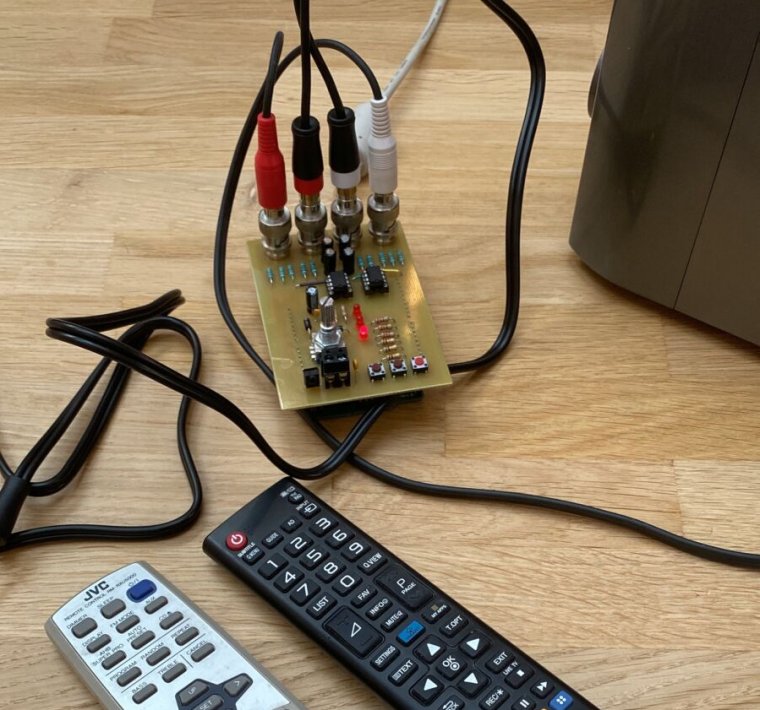

The students were (for the most part) really happy. By week five, a regular group were showing up early in the morning and leaving sometime after five in the evening. At the end of the project period, these students were way ahead of where we expected our first years to be at this point under the old curriculum—at least in terms of what they could do in practice: laying out circuits, taking measurements, soldering components, calculating required resistor values. Of course, the depth of knowledge at a theoretical level wasn’t as easy to demonstrate in the project, so we have our doubts about that. However, the philosophy is about context. This project doesn’t require that depth. The next projects require an increasing level of depth.

Teachers were more familiar with the learning management system (though still struggling with it), but the new portfolio plugin for the learning management system was (and is) inadequate. Students didn’t know how to use it, the mentors didn’t know how to use it, and nobody took the time to learn (there are only so many hours in the day). The end result was that a lot of students that we thought were performing really well—and even had demonstrated that their devices worked—did not submit any evidence at all for grading.

It was a weird experience: high student satisfaction, low-to-middling teacher satisfaction, and low-to-middling academic results.

Needed tweaks

One thing that became clear to the teachers is that they really need to change their lessons. The idea is that you really build your lessons around the project. That often means taking a top-down approach, where you first focus on how and why you should do something, and only afterwards build the theoretical underpinnings up. Now that the teachers have experienced this, a number are going back through their material and reshuffling to the match the project better.

Another issue was the mentoring. In the first semester, we trialed a tool that was advertised as a good way for students to track their own progress (and for mentors to track student progress). It was a failure. Feedback was also still an issue, because teachers were still lumbering themselves with multiple assignments that they then needed to check, which is a very slow process.

The project for the second half of the semester—currently underway—is not a kit project, but was still well defined and relatively complete. And again, the teachers and students are dealing with the mismatch between the project requirements and the order of their lessons.

We now track student progress much more simply: each mentor group keeps a single power point file. Every student adds (at least) two slides that summarizes the week’s activities and the plan for next week. On top of that, a slide that tracks the progress of the group’s project and the current project budget. It is very quick for the students to go through this with their mentor and the mentor to ask questions. Even better, it is excellent evidence for personal and project planning that has already been reviewed and had feedback.

We have also changed the way feedback is delivered. First, we have built in a scheduled feedback moment in the middle of the project period. In these moments, each project group gets feedback from all the teachers in one go. Second, the learning management system has a feedback tool built in. In this tool, the teacher gives oral feedback to the student in class (or wherever) and the student writes a summary of the feedback in the tool. The teacher can then rate the student (good, middling, poor) and respond to the summary, and you’re done. For the teacher, this is much quicker, and it assesses the student’s response to the feedback rather than the feedback itself, which is the more important aspect.

Another aspect that still needs improvement is ease of assessment. At the moment, we still assess in islands, while the goal is an integral assessment. The only reason that this hasn’t been changed is that this sort of under-the-hood change needs to go through a multistage review process, which takes time. It will be ready for the students who start in February, but the current cohort will go through one year of island assessment, unfortunately.

To the second year and beyond

The students who started in February will be entering the second year soon. We have taken the lessons from the first two semesters on board. In each semester of the second year, half of the academic credits are in a single block with an attached project (a self-driving model car for this group). The project defines the content of the curriculum, and has to be expansive enough that every student can take ownership of one part of the project. The project is then supported by direct instruction, practical exercises, and more.

The second block is purely up to the students to choose. There are no scheduled lessons, and the students are instead given a coach. The only hard limit on what the students can choose to study is that someone qualified has to be able to assess them. In practice, the students are clustered by their interests, and assigned a coach who can provide guidance at either a high level—the coach does not have detailed subject knowledge and guides the learning process—or a low level—the coach has detailed subject knowledge and can provide instruction as well as guiding the learning process.

Even though we have not begun, about half the students have already made choices. That, as expected, turned into a negotiation process as well. There are some things that we simply will not support (how to install industrial equipment, for instance). And we will not let students become too narrow in their interests.

Essentially, the students come with a vague idea, which we encourage them to turn into something concrete. Then we review that, and make changes with the students alongside. The nice thing is that with the clustering of interests, the projects and topics are also quite similar, so this negotiation process is quite quick. My impression is that both the teachers and the students are in a superposition of excited and terrified by this process.

A long hard year

It has been a long and hard year. The pandemic has made everything a little more difficult, and the teachers had to work a lot harder. We have made some mistakes along the way. But we are also in a much better place than we were a year ago. Most of the teachers are confident that they can make it work. The end result will not be exactly what I envisioned at the beginning, but it will have all the hallmarks of the underlying philosophy.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1822723