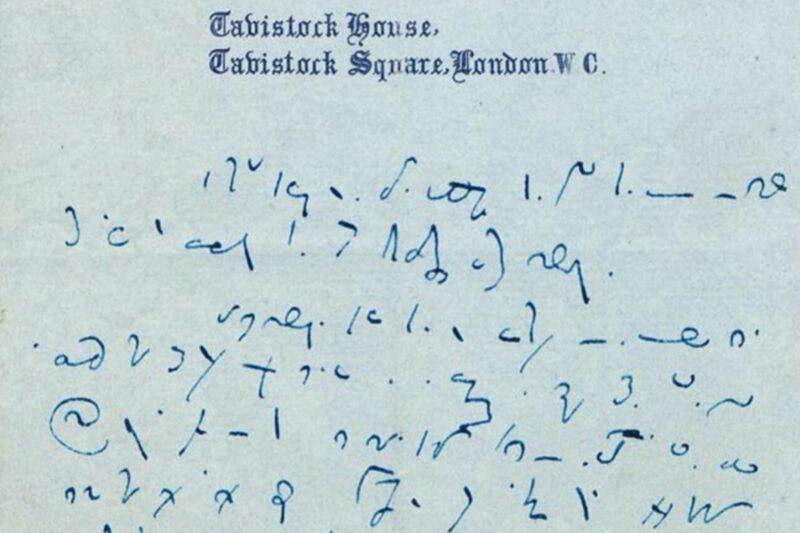

Amateur sleuths help solve 160-year mystery by decoding Charles Dickens letter

Last October, a collaboration called The Dickens Code project made a public appeal to amateur puzzle fans and codebreakers for assistance in decoding a letter written by Victorian novelist Charles Dickens in a tortuously idiosyncratic style of shorthand. The crowd-sourced effort helped scholars piece together about three-quarters of the transcript. Shane Baggs, a computer technical support specialist from San Jose, California, won the overall contest, while a college student at the University of Virginia named Ken Cox was declared the runner-up.

Dickens himself hardly needs an introduction, deemed by many to be the greatest novelist of the Victorian era. Great Expectations, Oliver Twist, A Tale of Two Cities, and of course, his timeless 1843 novella A Christmas Carol, are just a few of the works contributing to that well-deserved reputation. A lesser-known aspect of Dickens’ life is that he taught himself a particularly difficult form of shorthand as a teenager, relying on an 18th-century manual called Brachygraphy by shorthand writer Thomas Gurney. Dickens mentions this in passing in his semi-autobiographical novel David Copperfield:

I bought an approved scheme of the noble art and mystery of stenography (which cost me ten and sixpence); and plunged into a sea of perplexity that brought me, in a few weeks, to the confines of distraction. The changes that were rung upon dots, which in such a position meant such a thing, and in such another position something else, entirely different; the wonderful vagaries that were played by circles; the unaccountable consequences that resulted from marks like flies’ legs; the tremendous effects of a curve in a wrong place; not only troubled my waking hours, but reappeared before me in my sleep.

It took Dickens about a year to master Gurney’s Brachygraphy, and he spent three years using the shorthand as a court reporter. He also began adding his own unique symbols to write personal memos to himself, maintain teaching notebooks, write letters, and so forth. Alas, very few examples survive. There are only about 10 currently known manuscripts of Dickens’ shorthand, dating from the 1830s to the late 1860s. Several of these remain undeciphered, including a letter from the 1850s and a set of shorthand booklets collected by Dickens’ shorthand pupil, Arthur Stone (the son of his friend and neighbor).

The Dickens Code project is the brainchild of two Dickensian scholars: Claire Wood of the University of Leicester, and Hugo Bowles of the University of Foggia. “Dickens’s shorthand has proved extremely difficult to decode,” they wrote on the project’s website. For those seeking to crack the code, it helps to identify the original source material, although “in most cases, experts have been unable to locate the source texts used for the exercises,” they wrote. “They could be published or unpublished passages written by Dickens, or by another author.”

One of the samples of Dickens’ shorthand is a dictation exercise headed “Sydney Smith,” likely arising from the shorthand lessons he gave to Arthur Stone. Dickens was a great admirer of a reverend philosopher of that name, often carrying around a copy of Smith’s Elementary Sketches of Moral Philosophy. Dickens admired Smith so much, in fact, that he named his seventh son Sydney Smith Haldimand Dickens.

So which Sydney Smith did the dictation exercise refer to—the son or the philosopher? According to Wood and Bowles, this one was fairly easy to decipher thanks to a known symbol meaning “world.” They just had to search for occurrences of “world” in the philosopher’s works, which yielded about 10 candidates. But only one of those used “world” in the first line of a paragraph: a lecture entitled “On the Conduct of the Understanding.” Wood and Bowles think it makes sense that Dickens would have dictated something by his favorite philosopher to Stone as part of the latter’s shorthand lessons. Once they had identified the text, it was relatively simple to complete the rest of the transcription.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1832843