Compression Attached Memory Modules may make upgradable laptops a thing again

Of all the PC-related things to come out of CES this year, my favorite wasn’t Nvidia’s graphics cards or AMD’s newest Ryzens or Intel’s iterative processor refreshes or any one of the oddball PC concept designs or anything to do with the mad dash to cram generative AI into everything.

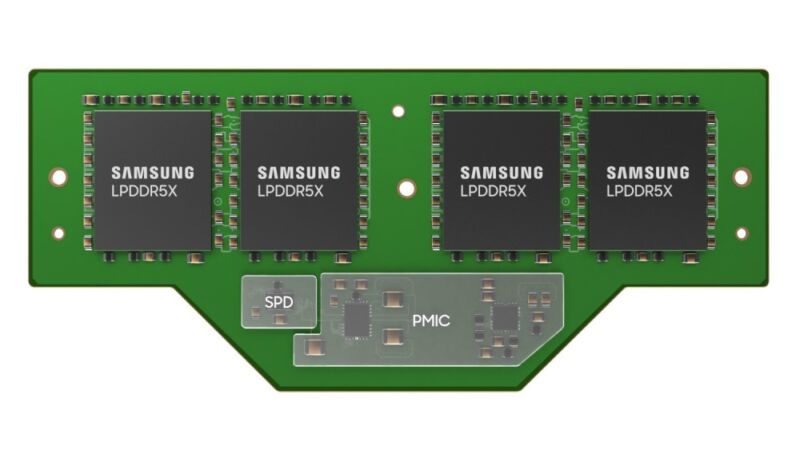

No, of all things, the thing that I liked the most was this Crucial-branded memory module spotted by Tom’s Hardware. If it looks a little strange to you, it’s because it uses the Compression Attached Memory Module (CAMM) standard—rather than being a standard stick of RAM that you insert into a slot on your motherboard, it lies flat against the board where metal contacts on the board and the CAMM module can make contact with one another.

CAMM memory has been on my radar for a while, since it first cropped up in a handful of Dell laptops. Mistakenly identified at the time as a proprietary type of RAM that would give Dell an excuse to charge more for it, Dell has been pushing for the standardization of CAMM modules for a couple of years now, and JEDEC (the organization that handles all current computer memory standards) formally finalized the spec last month.

Something about seeing an actual in-the-wild CAMM module with a Crucial sticker on it, the same kind of sticker you’d see on any old memory module from Amazon or Newegg, made me more excited about the standard’s future. I had a similar feeling when I started digging into USB-C or when I began seeing M.2 modules show up in actual computers (though CAMM would probably be a bit less transformative than either). Here’s a thing that solves some real problems with the current technology, and it has the industry backing to actually become a viable replacement.

From upgradable to soldered (and back again?)

It used to be easy to save some money on a new PC by buying a version without much RAM and performing an upgrade yourself, using third-party RAM sticks that cost a fraction of what manufacturers would charge. But most laptops no longer afford you the luxury.

Most PC makers and laptop PC buyers made an unspoken bargain in the early- to mid-2010s, around when the MacBook Air and the Ultrabook stopped being special thin-and-light outliers and became the standard template for the mainstream laptop: We would jettison nearly any port or internal component in the interest of making a laptop that was thinner, sleeker, and lighter.

The CD/DVD drive was one of the most immediate casualties, though its demise had already been foreshadowed thanks to cheap USB drives, cloud storage, and streaming music and video services. But as laptops got thinner, it also gradually became harder to find Ethernet and most other non-USB ports (and, eventually, even traditional USB-A ports), space for hard drives (not entirely a bad thing, now that M.2 SSDs are cheap and plentiful), socketed laptop CPUs, and room for other easily replaceable or upgradable components. Early Microsoft Surface tablets were some of the worst examples of this era of computer design—thin sandwiches of glass, metal, and glue that were difficult or impossible to open without totally destroying them.

Another casualty of this shift was memory modules, specifically Dual In-line Memory Modules (DIMMs) that could be plugged into a socket on the motherboard and easily swapped out. Most laptops had a pair of SO-DIMM slots, either stacked on top of each other (adding thickness) or placed side by side (taking up valuable horizontal space that could have been used for more battery).

Eventually, these began to go away in favor of soldered-down memory, saving space and making it easier for manufacturers to build the kinds of MacBook Air-alikes that people wanted to buy, but also adding a point of failure to the motherboard and possibly shortening its useful life by setting its maximum memory capacity at the outset.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1995134