Dark Archives: Come for the floating goat balls, stay for the fascinating science

When you think about medical librarians and rare book specialists, chances are you picture them poring over rare tomes in a dusty archives—and chances are, you wouldn’t be wrong. But when Megan Rosenbloom set out to separate fact from fiction on the existence of rare books bound in human skin, her investigations took her to some uncommon places—like an artisanal tannery in upstate New York, where the floor resembled “Mountain Dew with chunks floating in it,” and emptying drums of tanning effluvia might just unleash a few floating goat testicles among the mix.

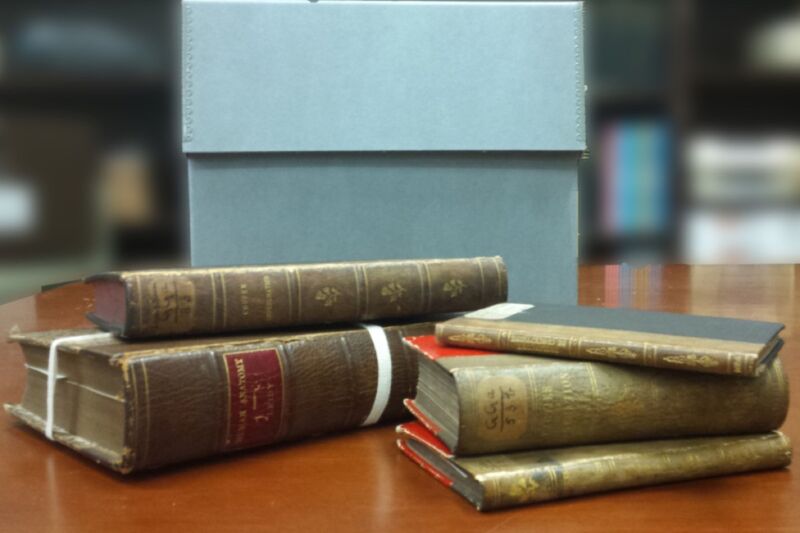

The technical term is “anthropodermic bibliopegy,” and Rosenbloom first became fascinated with this macabre practice in 2008, while she was still in library school and working for a medical publisher. While strolling through the vast collection of medical oddities at the famed Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, she came upon a glass display case holding an intriguing collection of rare books uncharacteristically displayed with their covers closed. The captions informed her that they had been bound in human skin, along with a leather wallet.

She was shocked to learn that such bindings were typically created by doctors as luxury items in their private rare book collections. “This wasn’t a doctor learning about anatomy through dissection,” Rosenbloom told Ars. “It wasn’t a specimen of rare disease used to educate people. Yet it didn’t seem like the doctors who made these books were Hannibal Lecter-type serial killers. They seemed to be upstanding doctors in the community. And I couldn’t understand in what context a seemingly normal doctor would feel okay doing that.”

Thus began a years-long journey, culminating with the publication in October of Dark Archives: A Librarian’s Investigation into the Science and History of Books Bound in Human Skin, an engaging, thoughtful exploration of this morbid practice, handled with remarkable sensitivity. Rosenbloom is now a medical librarian in charge of the medical collections at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, as well as a member of the Order of the Good Death and co-founder of that organization’s Death Salon, devoted to fostering conversations and scholarship about mortality and mourning.

Her adventures in anthropodermic bibliopegy resulted in the founding of the Anthropodermic Book Project, a scientific collaboration that seeks to build a census of all the alleged books bound in human skin around the world, testing them to determine whether the bindings are truly human in origin. “We get emails probably once a week now from random people who think that Grandpa had a human skin book in their attic or something,” Rosenbloom said.

One of those confirmed books belongs to Harvard University’s Houghton Library: Des destinées de l’ame by Arsène Houssaye, created by one Dr. Ludovic Bouland of Strasbourg, who died in 1932. It was confirmed by Harvard chemist Daniel Kirby, who used peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF) to make the determination. The same method has been used to confirm the authenticity of all five books purported to be bound in human skin in the Mütter Museum. I’ll let Rosenbloom explain how it works:

First, remove a tiny chunk of a book’s binding with a scalpel or sharp tweezers; if the chunk is visible to the human eye, it is more than enough. The sample is digested in an enzyme called trypsin and the mixture is dropped onto a MALDI ( matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization) plate. The MALDI plate is placed into a mass spectrometer, where lasers irradiate the sample to identify its peptides (the short chains of amino acids that are the building blocks of proteins) and create a peptide mass fingerprint (PMF). The “fingerprint” looks like a line graph of peaks and valleys, and each fingerprint corresponds with an entry in a library of known examples from animals. Each animal family shares a strain of protein markers that act as reference points scientists can use to distinguish one from another.

As of May 2019, the Anthropodermic Book Project had identified 50 books rumored to have human skin bindings, and had tested 31, 13 of which turned out to be fake. But 18 really are bound in human skin. They include a book housed in Surgeons’ Hall Museums in Edinburgh, Scotland, bound in the skin of a killer named William Burke. Burke was an infamous body snatcher who, with William Hare, killed 16 people in 1828 and sold the corpses to a Scottish anatomist named Robert Knox, who used them for dissection during his lectures.

Among the confirmed books in the Mütter Museum’s collection is one bound in the skin of a Civil War soldier. Another once belonged to a 19th century Philadelphia physician named John Stockton Hough. In January 1869, Hough was performing an autopsy on the corpse of a woman named Mary Lynch, and found tiny worms wriggling in a cyst in her pectoral muscles. It was the first known case of trichinosis in the city. Perhaps that’s why Hough decided to remove a large slice of Mary Lynch’s skin from her thighs, tossing them into a chamber pot to better preserve them. The salt and acid in urine acts as a pickling brine, a key first step in the tanning process.

Rosenbloom picked up that nugget of wisdom during her visit to Pergamena, an artisanal tannery in New York’s Hudson Valley run by Jesse Meyer—part of a long line of tanners dating back to 16th century Germany. Ever the inquiring scientist, Rosenbloom wanted to know exactly how one would go about creating a book binding out of human skin. “A lot of artisan trades didn’t really write down how they did things,” she said. “It was just apprenticeships. They weren’t exactly keeping manuals.” The process is much the same as that used to tan animal skins, and Pergamena is one of the few remaining places where traditional 19th century tanning techniques are used.

Her account of the tannery visit is one of the highlights of the book, giving Rosenbloom prime fodder for her sly, self-deprecating humor. She was particularly struck by the powerful odor, strugging to find the words to describe it. “It was not merely a smell,” she writes in Dark Archives. “It felt like having raw animal organs stuffed into my mouth and pulled through my nose.” (The smell permeated her old Keds, and she had to ditch them on the drive back home.) As for the aforementioned floating goat balls, Meyer confirmed that this was not an uncommon occurrence, since the hides he uses come from animals slaughtered for food. And sex organs typically stay with the hide.

There were also a fair share of frauds and fakes among the books that Rosenbloom and her colleagues with the Anthropodermic Book Project tested. For example, a piece of parchment in the Huntington collection was inscribed with the claim that it was “the skin of a White Man, taken by a Ingen,” who was roasted on a bed of coals, and his skin flayed to make the parchment. The parchment turned out to be be fake. Rosenbloom also dispels the myth of Nazi lampshades and other leather items—including books—being bound in human skin.

The closest contemporary analogue to binding books in human skin is the emerging practice of preserving someone’s tattoos after they die—the speciality of a mortician named Kyle Edwards, who runs Save My Ink Forever. Anecdotally, at least, Rosenbloom has found that people heavily invested in their tattoos are quite open to the prospect of having their skin art preserved after their deaths, despite the ‘ick’ factor. “Many of them don’t even blink an eye,” she said. “They’re like, ‘Yeah, I spent a lot of money on this, I have this beautiful piece of art, and it’s just going to rot in the ground. I would totally save that.'”

Per Rosenbloom, the results are pretty impressive, too. “They’re very clean and bright because they use that under-layer epidermis,” she said. “So even if you’re very old when you die, the tattoo ink goes all the through through the dermis. If you take off the top layer, it looks like the tattoo basically just got inked.”

Books bound in human skin also serve as a physical reminder for Rosenbloom of the extent to which many in the medical profession try to emotionally distance themselves from patients. “This is as a far as you can get from someone’s humanity, if you are cutting someone open on the autopsy table and decide, ‘You know, I’m going to save this piece of skin for later,'” she said. In the medical profession, residents frequently work 24 hours shifts and must deal with the constant stress of life and death situations.

“It’s the dark secret about the working lives of doctors,” said Rosenbloom. “They go into the profession because they care about people and want to help them, and then they get that empathy beaten out of them. If one is not able to work in humane conditions, and if the educational system does not insist upon, and prioritize, those humane conditions for their medical students and doctors, you are more likely to get people who are acting in insane ways. Doctors need to be able to reconnect themselves with their humanity in order to treat their patients humanely.”

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1717384