Did Nike Copy the Air Jordan Jumpman Logo?

Nike’s iconic Jumpman logo is designed to make Air Jordan wearers believe they can fly—or at least jump—like the brand’s namesake, NBA legend Michael Jordan. But the sight of Jordan’s airborne silhouette on shoes, shirts and storefronts never fails to bring the spirits of Jacobus “Co” Rentmeester crashing down to Earth.

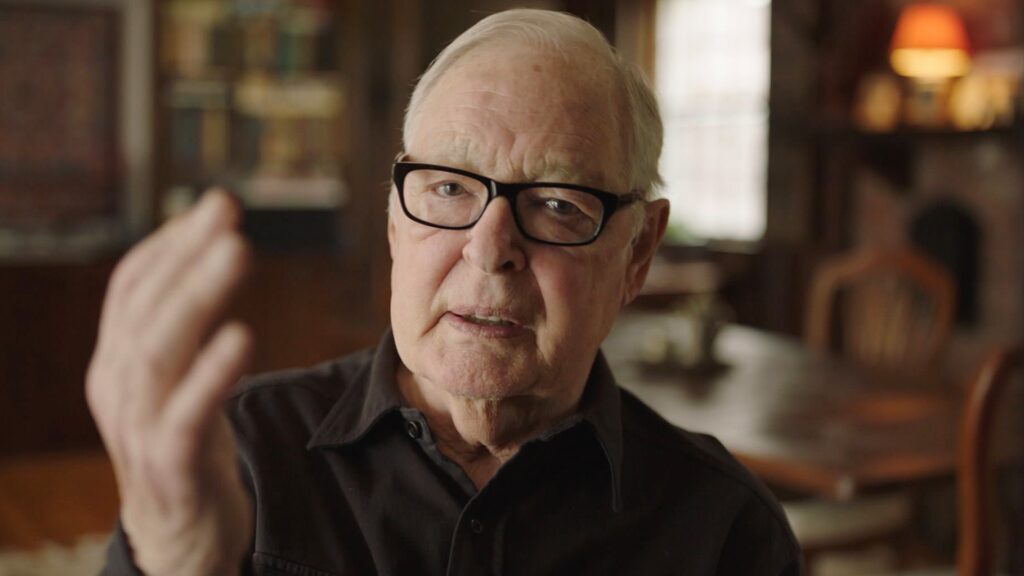

“I see it at least 10 times a day,” the 88-year-old photographer told ADWEEK, adding that the image always brings back a “painful period” in his life. That period is the subject of the new short documentary Jumpman, which recently premiered at the 2024 Tribeca Festival.

Directed by Rentmeester’s son-in-law, feature filmmaker Tom Dey, the film chronicles the now-retired cameraman’s decades-long effort to prove that he took the photograph that inspired the Air Jordan logo. He tried to make the case in court almost 10 years ago, only to see the judge dismiss it, giving Nike the win. (ADWEEK reached out to Nike for comment about the film and Rentmeester’s claims but received no reply as of press time.)

“I lost in the courts, but here we have a chance to talk to the public,” Rentmeester said of the impetus for the Jumpman film, which raises compelling questions about the ethical gray areas that can complicate the relationship between major brands and creators. “We can show them all the details, documents, letters and so forth, and let them make up their minds.”

“We hope that the film is a conversation-starter about authorship and appropriation,” added Dey, whose previous credits include Shanghai Noon and Failure to Launch. “We want other artists to be able to avoid what Co went through if at all possible.”

Taking flight

To be clear, Rentmeester isn’t claiming to have taken the image that Nike used as the direct model for the Jumpman logo. That photograph was commissioned by Nike in 1984 and snapped by Chuck Kuhn, who died in 2020. However, Dey’s film argues that Kuhn’s picture was directly modeled after Rentmeester’s own photograph of Jordan, which appeared in an Olympics-themed issue of Life magazine earlier that same year.

“I was asked to do a photo essay of athletes in outstanding situations,” recalled Rentmeester, who started his career as a photojournalist covering the Watts Riots and the Vietnam War before moving into editorial and advertising work. One of those athletes was a young Jordan, then a star player at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill and on the cusp of entering the NBA draft.

The “outstanding situation” that Rentmeester devised for Jordan required the 21-year-old player to take flight toward a hoop that stood on a grassy knoll beneath a blue sky.

“Normally, people would have taken Jordan onto a basketball court, but I had this unique idea,” the photographer said.

He directed Jordan to leap into the air with a basketball in his left hand and his legs splayed in near-perfect ballet form—a nod to the masterful grand jetés performed by celebrated dancer Mikhail Baryshnikov.

“Co told me that he wanted to create an image that people would never forget,” Dey said. “The irony is that people will never forget it—but at great personal cost to him.”

Losing altitude

Rentmeester’s Life photo essay debuted to great acclaim, bolstering his creativity and his reputation. But on a trip to Chicago months later, he noticed a billboard that, as he says in Dey’s film, made him feel as though he’d been “hit in the stomach.”

There was Jordan—newly signed to the Chicago Bulls—floating above the Windy City skyline, once again mimicking a Baryshnikov grand jeté. It was Kuhn’s Nike-commissioned photograph, but Rentmeester suspected what the Oregon-based shoe company had used as a reference.

Earlier that summer, an ad agency working with Nike had contacted Rentmeester requesting duplicate slides from his shoot with Jordan, vowing in writing that they wouldn’t copy or duplicate them. The agreed-upon fee was $150. “They said they needed them for research,” Rentmeester said.

Reaching out to Nike, the photographer threatened legal action over what he perceived to be similarities between the two images, but was persuaded to accept $15,000 and the possibility of future employment—though that employment ultimately never materialized. It was an offer that proved impossible to refuse for a freelance photographer supporting a family on an often unpredictable salary.

“I felt very restricted because as a single individual taking on the law firms that Nike could produce, there seemed like very little chance that I would go far,” Rentmeester said of why he accepted that deal, adding that he would have happily licensed his Life pictures to Nike for both the billboard and the Jumpman logo had they asked. “They simply ignored me because they felt they were powerful enough to just throw me under the bus in a certain way.”

Three decades later, Rentmeester took Nike to court, filing a copyright infringement suit in federal court in Portland, Ore., where the shoe giant is based. Asked about the reason for the 30-year gap, Dey said his father-in-law wanted to wait until retirement, as his agent and lawyer had advised him at the time that suing Nike might impact his professional career.

When Rentmeester learned that the statute of limitations had not expired in 2014, he reached out to lawyer who was working with Life. (The magazine ceased regular publication in 2000, but has been revived in the years since. It is currently owned by Dotdash Meredith, which plans a relaunch later this year in collaboration with Bedford Media.)

“By that point, he felt he had nothing to lose,” Dey said.

From the beginning, though, Rentmeester knew that winning would be a steep challenge and was disappointed—but not entirely surprised—when the Ninth Circuit judges sided with Nike, pointing to minor differences between his picture and Kuhn’s as evidence for their decision to dismiss the case. (The U.S. Supreme Court similarly wasn’t persuaded when Rentmeester appealed the ruling in 2019.)

“The panel held that Rentmeester plausibly alleged the first element of his copyright claim—that he owned a valid copyright in his photo,” the Ninth Circuit judges noted in their decision. “Rentmeester did not, however, plausibly allege that Nike copied enough of the protected expression from his photo to establish unlawful appropriation.”

In his opinion, Judge Paul J. Watford pointed out the discrepancies he saw between Rentmeester and Kuhn’s photographs, noting the different positions of Jordan’s limbs as well as the placement of the two basketball hoops. “In our view, these differences in selection and arrangement of elements, as reflected in the photos’ objective details, preclude as a matter of law a finding of infringement,” Watford wrote.

But Rentmeester feels the judges’ reading of the law was shortsighted. “It’s easy for them to defend certain things by getting very technical and pointing out that a thumb or a foot is not in the same place in their version as it was in mine,” he explains.

Lessons learned

While Rentmeester insists he’s never estimated how much money he missed out on when Nike commissioned its own Jumpman image, Jordan himself is believed to have made over $1.5 billion from the Air Jordan brand over the past three decades. Both the photographer and Dey were quick to say they don’t believe the now-retired player played any conscious role in orchestrating the overlap between the two pictures.

“I can only be positive about his involvement in my shoot,” Rentmeester said. “He was a gentleman; he listened to me and did his best. Afterward, I never heard from him again. He had a major contract worth millions of dollars, so I feel like he had to listen to Nike.”

“I would love to hear from Jordan more than Nike [today]—just to see what his memories are,” Dey added. “I don’t know if he would ever want to [comment] because that brand is such a golden goose.”

While Jordan has never commented on Rentmeester’s claims directly, he did discuss Kuhn’s photo in a 1997 issue of Hoop magazine that is not available online. According to ABC News and ESPN, the photographer’s suit claimed that interview backed up his assertion that Jordan was performing a ballet move in the Nike-commissioned version of Jumpman.

Having worked in the advertising world himself as a director, Dey sees his father-in-law’s story as a “cautionary tale” for other artists whose work attracts the attention of major brands and corporations. “I absolutely believe that brands have an obligation to respect the authorship of creators,” he argued. “It’s in their best interest to do so and to have a productive and creative collaboration with creators. When there’s a baseline of respect that goes both ways, everybody wins.”

Finding that baseline is even more urgent at a time when young artists have ready access to high quality cameras via their smartphones, while also watching the proliferation of AI images in real time. In that climate, Dey said a photograph needs to be treated as “more than the sum of its parts.”

“If you break down the individual components of any piece of art, like a poem or a painting—as what happened during our lawsuit—you’re going to be able to find differences,” the director said. “But we feel that it’s important to look at these things holistically. In this instance, that didn’t happen, and it caused great harm to the artist.”

Postgame thoughts

For his part, Rentmeester said he largely had positive relationships with his advertising clients during the course of his career, and appreciated that they always had a “very strict directive” for what they were looking for.

“It’s very disciplined work,” he noted. “I never got into any conflicts before this because I was just working for a client. Life magazine was my client [for the Jordan picture], and how it was distorted and taken away from me was a very painful period that I had to go through.”

Dey’s film does make clear that Rentmeester’s life and legacy extend well beyond his tangled history with Nike. “I’ve been blessed,” the photographer says in the documentary’s final moments. “I hope other young people will look at the situation and say, ‘Photography is an art, and it should be protected.’”

Still, he admits to avoiding the Air Jordan logo whenever possible, including at the multiplex. Asked whether he saw Ben Affleck’s 2023 film, Air—which recounted the creation of Nike’s signature shoe but relegated the Jumpman logo to a mid-credits footnote that didn’t mention Rentmeester—the photographer indicates that it’s not in his Prime Video queue.

“I stayed away from it,” Rentmeester said. “It would just have irritated me.”

https://www.adweek.com/brand-marketing/did-nike-copy-air-jordan-jumpman-logo/