DNA analysis revealed the identity of 19th century “Connecticut vampire”

Back in 1990, children playing near a gravel pit in Griswold, Connecticut, stumbled across a pair of skulls that had broken free of their graves in a 19th century unmarked cemetery. Subsequent excavation revealed 27 graves—including that of a middle-aged man identified only by the initials “JB55,” spelled out in brass tacks on his coffin. Unlike the other burials, his skull and femurs were neatly arranged in the shape of a skull and crossbones, leading archaeologists to conclude that the man had been a suspected “vampire” by his community. Scientists finally found a likely identification for JB55, describing their findings in a paper published this summer in the journal Genes.

Analysis of JB55’s bones back in the 1990s indicated the man had been a middle-aged laborer, around 55 when he died (hence, JB55, the man’s initials and age at death). The remains also showed signs of lesions on the ribs, so JB55 suffered from a chronic lung condition—most likely tuberculosis, known at the time as consumption. It was frequently lethal in the 1800s, due to the lack of antibiotics, and symptoms included a bloody cough, jaundice (pale, yellowed skin), red and swollen eyes, and a general appearance of “wasting away.” The infection frequently spread to family members. So perhaps it’s not surprising that local folklore suspected some victims of being vampires, rising from the grave to sicken the community they left behind.

Hence the outbreak of the so-called Great New England Vampire Panic in the 19th century across Rhode Island, Vermont, and eastern Connecticut. It was common for families to dig up the bodies of those who had died from consumption to look for signs of vampirism, a practice known as “therapeutic exhumation.” If there was liquid blood in the organs (especially the heart), a bloated abdomen, or if the corpse seemed relatively fresh, this was viewed as evidence of vampirism. In such cases, the organs would be removed and burned, the head sometimes decapitated, and the body reburied. Given JB55’s lung condition and the fact that the signs of decapitation, he was likely a suspected vampire.

-

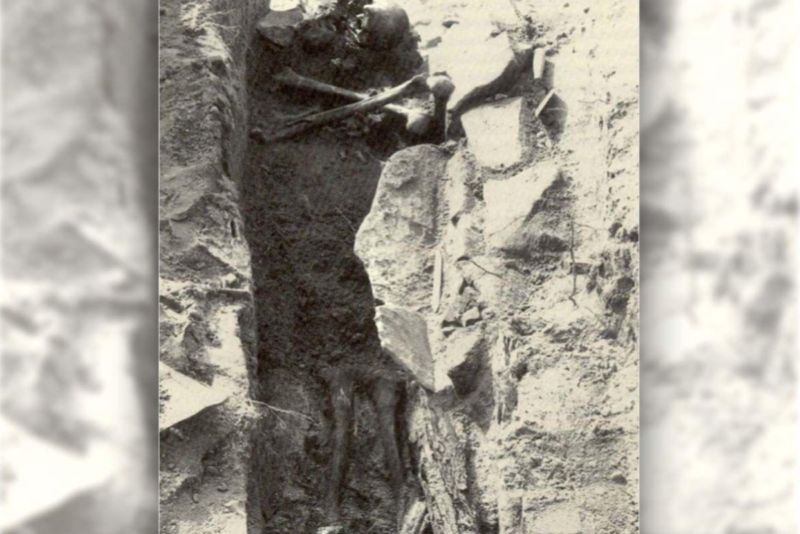

Photograph of JB55 showing bones arranged in a skull and crossbones.J. Daniels-Higginbotham/Genes

-

JB55’s ribs showed signs of lesions, indicating a chronic lung infection like tuberculosis.J. Daniels-Higginbotham/Genes

-

A fragment of the coffin that held the remains of the man believed to be John Barber is hardwood, decorated with brass tacks hammered into the initials “JB55.”Courtesy of Connecticut State Archaeologist

-

A diagram of the cemetery where the desecrated grave of the alleged vampire was found.Bill Keegan/Connecticut State Archaeologist

“This was being done out of fear and out of love,” co-author Nicholas F. Bellantoni, a retired Connecticut state archaeologist who worked on the case in the early 1990s, told the Washington Post. “People were dying in their families, and they had no way of stopping it, and just maybe this was what could stop the deaths. They didn’t want to do this, but they wanted to protect those that were still living.”

Researchers at the National Museum of Health and Medicine (NMHM) took a sample from one of JB55’s femurs in the early 1990s. The DNA was analyzed, but it wasn’t possible at the time to glean sufficient information to make reliable identification. “This case has been a mystery since the 1990s,” Charla Marshall, a forensic scientist with SNA International in Virginia, told the Washington Post. “Now that we have expanded technological capabilities, we wanted to revisit JB55 to see whether we could solve the mystery of who he was.”

For this most recent analysis, the researchers used Y-chromosomal DNA profiling and cross-referenced the genetic markers with an online genealogy database. The closest match had the last name of “Barber.” A newspaper notice from 1826 recorded the death of a 12-year-old boy named Nathan Barber, son of one John Barber of Griswold. It just so happens that a grave near that of JB55 bore the initials “NB13” on the coffin lid. That’s strong evidence that JB55 is probably John Barber, while NB13 was his son. But there was no other historical or genealogical information about either of them.

“To our knowledge this is the first study that applies DNA testing to identify the remains of a historical case with no presumed identity,” the authors wrote, unlike DNA analysis for such high-profile historical figures as Richard III or the Romanov family, where the DNA profiles can be compared to that of living relatives. “Future work involving genetic genealogy may lead to living descendants of JB55, and possibly verify the identity of the Griswald, Connecticut vampire as John Barber.”

DOI: Genes, 2019. 10.3390/genes10090636 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1637481