Effie Case Study: How Microsoft Helped Guide a Handwritten Language Into the Digital Age

With C-suite leaders from iconic brands keynoting sessions, leading workshops and attending networking events, Brandweek is the place to be for marketing innovation and problem-solving. Register to attend September 23–26 in Phoenix, Arizona.

More than a mere collection of words, language provides a unique perspective of the world. Each time one disappears, so does its way of seeing things.

When considering that experts fear 90% of languages around the globe could vanish over the next century, that’s a lot of viewpoints to lose.

In the Effie Award-winning campaign “ADLaM: An Alphabet to Preserve a Culture,” McCann New York revealed how Microsoft worked with the Fulani people of West Africa to keep their language—and, therefore, their wisdom, creativity, and history—alive in the digital era.

The problem

Although around 60 million Fulani people communicate through their native tongue of Pulaar, the language hasn’t had an alphabet for the majority of its existence. The only way to use it was to speak it.

This changed in the late 1980s, when two Fulani brothers, Ibrahima and Abdoulaye Barry, began creating a Pulaar alphabet. They dedicated themselves to the task, filling notebooks with shapes and symbols. Sometimes they closed their eyes and tried to draw new characters based on sound alone.

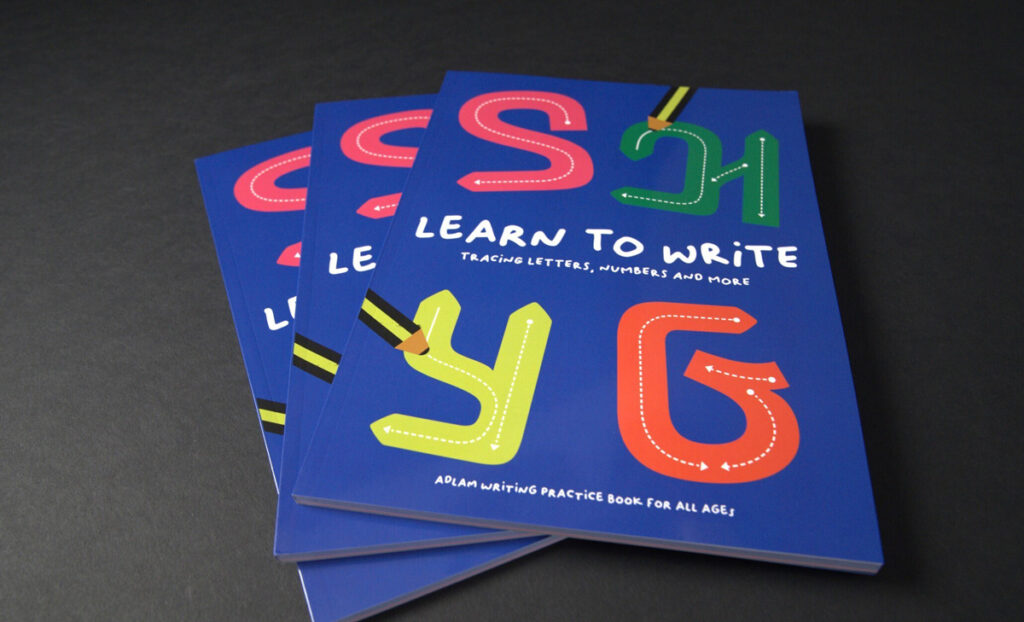

Eventually, the brothers settled on a 28-letter system that’s become known as ADLaM, an acronym featuring the alphabet’s first four characters that stands for Alkule Dandayɗe Leñol Mulugol, or “the alphabet that protects the people from vanishing.”

Despite the major achievement, ADLaM remained confined to pen and paper. The only way to use it was to write it by hand. This meant Pulaar speakers had to rely on another language for expressing themselves through email, text messages, and social media. If the Fulani people wanted to participate in business and conversations happening on digital channels, they had to leave their words behind.

The solution

In 2019, at the Barry brothers’ request, Microsoft got involved. Working alongside the brothers and Fulani community at large, the tech company began honing each ADLaM character.

“As a designer, it’s probably the coolest thing you could possibly ever work on,” said Kathleen Hall, Microsoft’s chief brand officer. “Talk about a legacy—it’s not like an ad that’s going to disappear in 10 years from now.”

Around two years later, the result was ADLaM Display, a digital typeface that runs on all Microsoft 365 products and services. Microsoft also made the font open source and shared it with Google, making it even more available and useful in modern life.

The results

If the goal was to help the Fulani people participate in the digital economy with their native tongue while safeguarding their culture for future generations—and it was—Microsoft achieved its mission. ADLaM Display is now available on Microsoft 365 applications, such as Word, Outlook, and PowerPoint. Entrepreneurs to educators use it every day.

“Empowering people is what Microsoft has always been about,” said Shayne Millington, chief creative officer at McCann New York. Millington noted there’s no shortage of stories about the tech company tackling similar problems, whether that’s preserving languages or buildings. “This is not a new space,” she added.

Microsoft didn’t need a massive advertising campaign to promote its ADLaM project; a video and blog post documenting the process was enough to get the word out. Surveys found American consumers held a more positive view of Microsoft following its work on ADLaM Display.

Microsoft’s Hall described the publicity aspect as more of a pull than a push. “We let it find its audience,” she said.

In another sense, Microsoft’s products themselves acted as the best possible medium to broadcast the ADLaM initiative to the people who could benefit the most from hearing it.

As Millington put it: “The global impact of this far exceeds anything an ad could ever do.”

https://www.adweek.com/creativity/effie-case-study-how-microsoft-helped-guide-a-handwritten-language-into-the-digital-age/