Egyptologists translate the oldest-known mummification manual

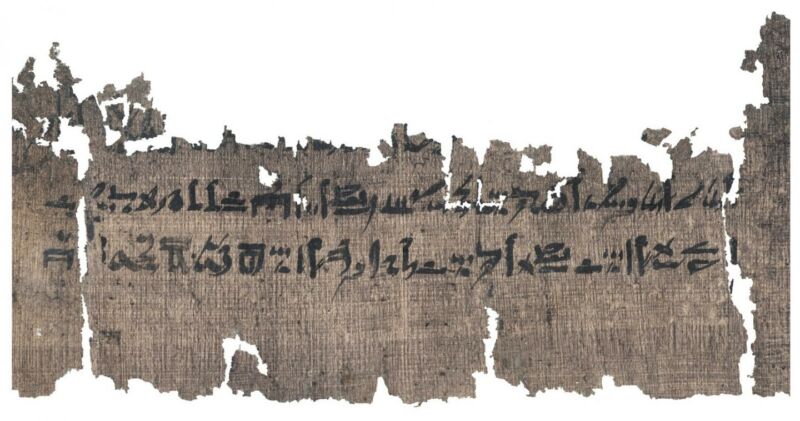

Egyptologists have recently translated the oldest-known mummification manual. Translating it required solving a literal puzzle; the medical text that includes the manual is currently in pieces, with half of what remains in the Louvre Museum in France and half at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark. A few sections are completely missing, but what’s left is a treatise on medicinal herbs and skin diseases, especially the ones that cause swelling. Surprisingly, one section of that text includes a short manual on embalming.

For the text’s ancient audience, that combination might have made sense. The manual includes recipes for resins and unguents used to dry and preserve the body after death, along with explanations for how and when to use bandages of different shapes and materials. Those recipes probably used some of the same ingredients as ointments for living skin, because plants with antimicrobial compounds would have been useful for preventing both infection and decay.

New Kingdom embalming: More complicated than it used to be

The Papyrus Louvre-Carlsberg, as the ancient medical text is now called, is the oldest mummification manual known so far, and it’s one of just three that Egyptologists have ever found. Based on the style of the characters used to write the text, it probably dates to about 1450 BCE, which makes it more than 1,000 years older than the other two known mummification texts. But the embalming compounds it describes are remarkably similar to the ones embalmers used 2,000 years earlier in pre-Dynastic Egypt: a mixture of plant oil, an aromatic plant extract, a gum or sugar, and heated conifer resin.

Although the basic principles of embalming survived for thousands of years in Egypt, the details varied over time. By the New Kingdom, when the Papyrus Louvre-Carlsberg was written, the art of mummification had evolved into an extremely complicated 70-day-long process that might have bemused or even shocked its pre-Dynastic practitioners. And this short manual seems to be written for people who already had a working knowledge of embalming and just needed a handy reference.

“The text reads like a memory aid, so the intended readers must have been specialists who needed to be reminded of these details,” said University of Copenhagen Egyptologist Sofie Schiødt, who recently translated and edited the manual. Some of the most basic steps—like using natron to dry out the body—were skipped entirely, maybe because they would have been so obvious to working embalmers.

On the other hand, the manual includes detailed instructions for embalming techniques that aren’t included in the other two known texts. It lists ingredients for a liquid mixture—mostly aromatic plant substances like resin, along with some binding agents—which is supposed to coat a piece of red linen placed on the dead person’s face. Mummified remains from the same time period have cloth and resin covering their faces in a way that seems to match the description.

Royal treatment

“This process was repeated at four-day intervals,” said Schiødt. In fact, the manual divides the whole embalming process into four-day intervals, with two extra days for rituals afterward. After the first flurry of activity, when embalmers spent a solid four days of work cleaning the body and removing the organs, most of the actual work of embalming happened only every fourth day, with lots of waiting in between. The deceased spent most of that time lying covered in cloth piled with layers of straw and aromatic, insect-repelling plants.

For the first half of the process, the embalmers’ goal was to dry the body with natron, which would have been packed around the outside of the corpse and inside the body cavities. The second half included wrapping the body in bandages, resins, and unguents meant to help prevent decay.

The manual calls for a ritual procession of the mummy every four days to celebrate “restoring the deceased’s corporeal integrity,” as Schiødt put it. That’s a total of 17 processions spread over 68 days, with two solid days of rituals at the end. Of course, most Egyptians didn’t get such elaborate preparation for the afterlife. The full 70-day process described in the Papyrus Louvre-Carlsberg would have been mostly reserved for royalty or extremely wealthy nobles and officials.

A full translation of the papyrus is scheduled for publication in 2022.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1747817