Even galaxies recycle

On Earth, recycling signs are everywhere, urging us to save our planet while we still can. In space, some galaxies apparently recycle without any signs to remind them.

At least one galaxy isn’t letting materials that could form potential stars go to waste. An international team of scientists led by astronomers Shiwu Zhang and Zheng Cai of Tsinghua University in China has found evidence that an enormous galaxy within an even larger nebula called MAMMOTH-1 is drawing in material from its surroundings to spawn new stars.

However, that material contains elements formed by past supernovae that are thought to have happened within galaxies, with the elements they created being flung into the nebula by the galaxy’s central black hole. This means that the galaxy, which the research team refers to as G-2, is now forming stars from material had previously been hurled out into intergalactic space by a galaxy—either itself or another nearby.

“Simulations have shown that recycling of gas—the re-accretion of gas that was previously ejected from a galaxy—could sustain star formation in the early Universe,” the researchers said in a study recently published in Science.

Recycling, stellar style

Stars fuel themselves with the energy that comes out of nuclear fusion, smashing atoms of hydrogen together into helium. Only massive stars (8 solar masses or more) go supernova, after they have fused all their hydrogen into helium. Gravity then causes the collapse of a massive star, which soon bursts into an extremely luminous explosion that blows away its outer layers. Supernovas cause shockwaves that can generate enough power to fuse new atomic nuclei—even metals such as iron.

But one star’s afterlife can mean another’s birth. After the explosion, the remains of the dead star scatter into space, swirling into the interstellar medium. While some of this material is forever lost to space, stars can still potentially incorporate some of the material created in the supernova.

The heavier elements created by supernovae can act as tracers for when stars have incorporated the remains of a previous generation of stars. While the majority of a newly formed star will always be hydrogen and helium, the degree to which there are heavier elements tells us something about the history of the material that went into its creation.

Don’t cross the streams

Raw material for star formation is abundant in MAMMOTH-1 nebula, and observations from the Subaru and Keck II telescopes have revealed there are three gaseous streams flowing from the nebula into one of the galaxies inside it. MAMMOTH-1 is an especially huge nebula that lives up to its name. The streams of gas from this nebula stretch an astounding 100 kiloparsecs (325,000 light years) away from the galaxy that is taking them in. These streams could supply the galaxy with what it news for a new generation of stars.

The research team created kinematic models, which show an object’s motion, of both the galaxy and nebula to see exactly how the gaseous streams were moving. It appears the streams are spiraling inward towards the galaxy, which they consider more evidence for an immense material that can be recycled into new stars.

The Subaru and Keck II observations revealed that these streams glowed with emission lines that indicated hydrogen and helium were present, which is to be expected. But there was also significant amounts of carbon. The presence of carbon shows that the cloud contains heavier elements that had likely come from stars that have long since died.

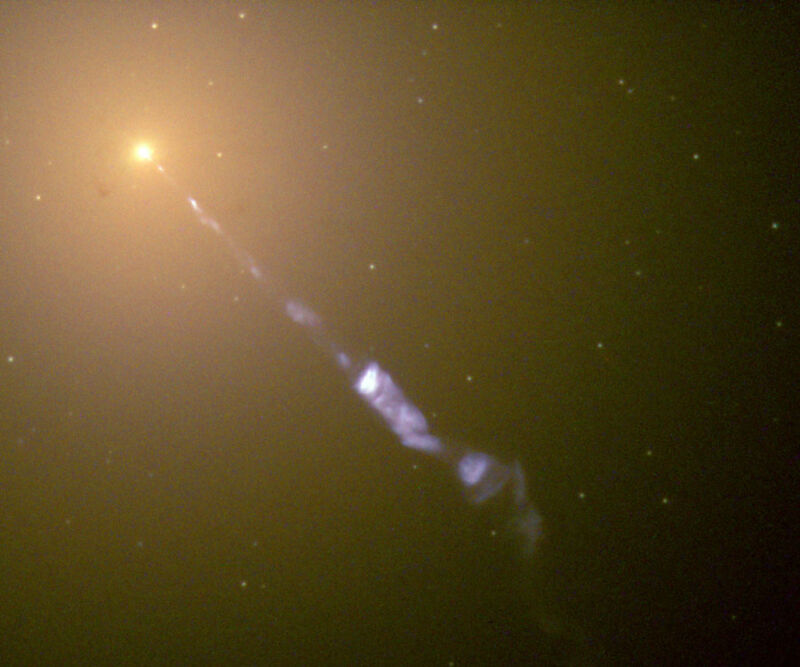

Something else that was discovered in the MAMMOTH-1 observations was that two of the streams of gas headed toward the galaxy pulling them in originated from the same quasar. Quasars develop when supermassive black holes at the center of galaxies devour enough material to emit jets of material and extreme radiation. These jets can eject material from the galaxy entirely

The researchers determined this quasar is most likely not located in the same galaxy that’s drawing in the material. So, this appears to be a case where one galaxy is recycling the material cast off from another.

Science, 2023. DOI: 10.1126/science.abj9192

Elizabeth Rayne is a creature who writes. Her work has appeared on SYFY WIRE, Space.com, Live Science, Grunge, Den of Geek and Forbidden Futures. When not writing, she is either shapeshifting, drawing, or cosplaying as a character nobody ever heard of. Follow her on Twitter @quothravenrayne

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1948741