First major modular nuclear project having difficulty retaining backers

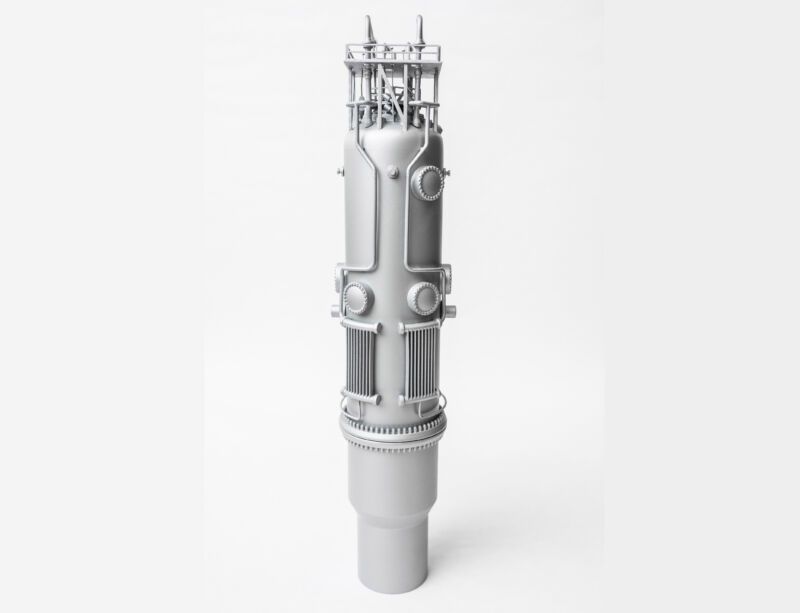

Earlier this year, the US took a major step that could potentially change the economics of nuclear power: it approved a design for a small, modular nuclear reactor from a company called NuScale. These small reactors are intended to overcome the economic problems that have ground the construction of large nuclear plants to a near halt. While each only produces a fraction of the power possible with a large plant, the modular design allows for mass production and a design that requires less external safety support.

But safety approval is just an early step in the process of building a plant. And the leading proposal for the first NuScale plant is running into the same problem as traditional designs: finances.

The proposal, called the Carbon Free Power Project, would be a cluster of a dozen NuScale reactors based at Idaho National Lab but run by Utah Associated Municipal Power Systems, or UAMPS. With all 12 operating, the plant would produce 720 MW of power. But UAMPS is selling it as a way to offer the flexibility needed to complement variable renewable power. Typically, a nuclear plant is either producing or not, but the modular design allows the Carbon Free Power Project to shut individual reactors off if demand is low.

But keeping a plant idle means you’re not selling any power from it, making it more difficult to pay off the initial investment made to produce it and adding to the financial risks. Further increasing risk is the fact that this is the first project of its kind—the NuScale website lists it as “NuScale’s First Plant.” All of this appears to be making things complicated for the Carbon Free Power Project.

According to one report, the US Department of Energy had originally planned to purchase the first reactor for research use, then turn it over to UAMPS. But now, the goal is apparently for the DOE to provide an annual supplement of about $130 million a year for a decade. However, that would be dependent upon annual renewals of the funding by Congress during that decade, which is yet another risk. Separately, to reach a target price for the power that is expected to be competitive with natural gas, the project has been made larger and its completion delayed by three years.

That has apparently been scaring off some utilities that had signed up for a slice of the project.

UAMPS runs a number of generating stations (many of them coal-based) that collectively serve needs throughout the US West from Wyoming and New Mexico to California. It distributes the power from these plants to small public utilities that often service a single small city. For the Carbon Free Power Project, UAMPS has been relying on those cities to buy a share of the project in return for a proportional share of the plant’s final generating capacity. With the changes in price and funding, a number of those utilities are dropping out.

There’s still plenty of time for UAMPS to find other participants among other utilities that it counts as customers, given that the plant isn’t expected to come on line until 2030. But the financial challenges suggest that small modular nuclear plants may struggle to get off the ground.

That shouldn’t be unexpected, as utilities are notoriously conservative—justifiably so, considering how much their customers rely on electricity. So any new electrical technology is likely to face some struggles as its customers learn to use it effectively and understand how to extract the most value of it. Typically, the government steps in to provide some support during this awkward phase, as it has done for wind and solar, and plans on doing for NuScale.

That said, a decade is a long way out for the completion of the first plant, given the trajectories that wind, solar, and storage prices have taken. Perhaps as critically, most utilities are already done with the learning period needed to use variable renewables effectively, when that period will only start for small modular reactors in 2030. It’s entirely possible that we’ll be ready to move forward with this nuclear technology at roughly the same time we’re becoming confident that we won’t need much of it.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1720177