From Vaporwave to Future Funk: Night Tempo artists talk Japanese aesthetics of cuteness and City Pop

This summer Digital Arts is looking at Japan’s most exciting new visual talent in our Tokyo DADA series. Last week saw things begin with a profile of illustrator Ushiki Masanori, continuing today in this look at how illustrators around the world are in love with a 1980s Japan they’ve never experienced.

With London paying host to a major new manga exhibition at the British Museum, along with seasons dedicated to manga legends such as Urasawa Naoki and live-action adaptations of Japanese cult faves, there’s never been a better time to celebrate the cool aesthetics of Japan as we head into 2020.

It was 18 years ago when French house duo Daft Punk confounded expectations by releasing the comeback single of One More Time.

A world away from their previously down and dirty dance music, the pop-house number also came with a new look for the act, eschewing the strange lo-fi energy of previous collaborator Michel Gondry for a music video that was essentially an anime episode condensed down to five minutes.

[embedded content]

Created by Tokyo’s revered Toei Animation under the supervision of manga and animation legend Leiji Matsumoto, the video would go on to be the opener of 2003’s Interstella 5555: The 5tory of the 5ecret 5tar 5ystem, an anime musical that served as visual accompaniment to Discovery, the classic Daft Punk album from a few years prior.

The space opera stylings of Matsumoto that had defined Saturday morning TV for kids growing up in late 70s Japan proved to be a perfect match for the retro grooves of the album, and Interstella 5555‘s mix of colour and psych led to the look of 2000s hip hop getting a distinctly Japanese flavour. Pharrell album portraits got that fun Bathing Ape (BAPE) touch straight from Tokyo; art megastar Kaws got his first break designing for the BAPE spin-off record label, while Takashi Murakami was putting psychedelic teddy bears – not apes – all over the Kanye West discography.

Cute suddenly had swagger, as long as it came from Japan. But in terms of dance music, only Daft Punk seemed to want to decorate the dancefloor with an anime aesthetic. With hip hop keeping all the Japanese illustrators for itself, and Gorillaz taking over the world with their own cartoon band, there seemed to be nowhere else for Interstella 5555‘s influence to grow. Contemporary talents became an entry point for any outsiders curious about the Japanese art world, and while an anime influence did colour their portfolios, that retro, joyous universe created by Matsumoto for a whole new audience seemed to disappear from view.

Fast forward almost two decades later though, when an offbeat music genre is born and a brand new generation emerges with their own visual take on Japanese pop culture.

City pop is the name of the scene, brought to you by the children of Interstella 5555.

French touch gets Japanese

2010, the year when Daft Punk made their first foray into hip hop production by collaborating with Pharrell Williams outfit N.E.R.D.

It was also the year vaporwave began to get the intention of the internet, a multimedia movement encompassing glitch art and the kind of music you hear when holding on the phone for a doctor’s appointment.

From the get-go the vaporwave aesthetic was one inspired by a unique imagining of 1980s Japan, with artists incorporating the Japanese language within their artwork and titles, alongside grainy VHS-grade images from the era. Numerous theories abound on this particular fetish of what was then a very Western phenomenon, mainly falling in the anti-capitalist vein by arguing it’s one mid-recession culture’s tongue-in-cheek worshiping of Japan’s peak, pre-1992 crash economy. Back then, this was the country which could afford to get David Bowie to make a TV commercial with entirely new music, making for a 1980s artefact which is as vaporwave as things can get.

The Japanese obsession at work would become most evident when vaporwave spawned the subgenre of ‘future funk’ circa 2012. Where vaporwave is the slow druggy sound of an economic comedown, future funk is the soundtrack of a culture at its party-time peak.

In a lo-fi take on the sample tapestry of Daft Punk’s Discovery, the genre merges 90s French house with faded samples of 80s Japanese ‘city pop’ across albums usually released on the medium of cassette. Maintaining a certain scratchy quality is crucial in this scene.

It may sound like a weird mix, but it’s one that’s seen future funk not only topple vaporwave as the internet’s most beloved musical niche, but also spread out into the nightlife scene where Daft Punk originally made their name during the rave years.

Acts like Korea’s Night Tempo roar in trade on Bandcamp with their tape-only releases, while America’s Yung Bae (above) is taking on nationwide tours and festival sets. Future funk is something you can actually dance to, much like the city pop music genre that got 1980s pop charts grooving.

An aspirational mix of yacht rock, boogie and funk, the long-dead genre has managed to gain a cult following on the same level of vaporwave and future funk thanks to suddenly viral hits like Mariya Takeuchi’s 1984 song Plastic Love, and a co-opting of the genre by today’s K-pop and J-pop idols.

City pop aficionados Night Tempo and Bae are currently future funk’s figureheads, but their anime-aping record sleeves reveal each artist’s true age and influence. They and their peers were children who didn’t necessarily grow up listening to city pop or watching those Matsumoto classics like Space Battleship Yamato and Galaxy Express 999, being instead raised on the sound and vision of Interstella 5555‘s homage to Japanese pop culture.

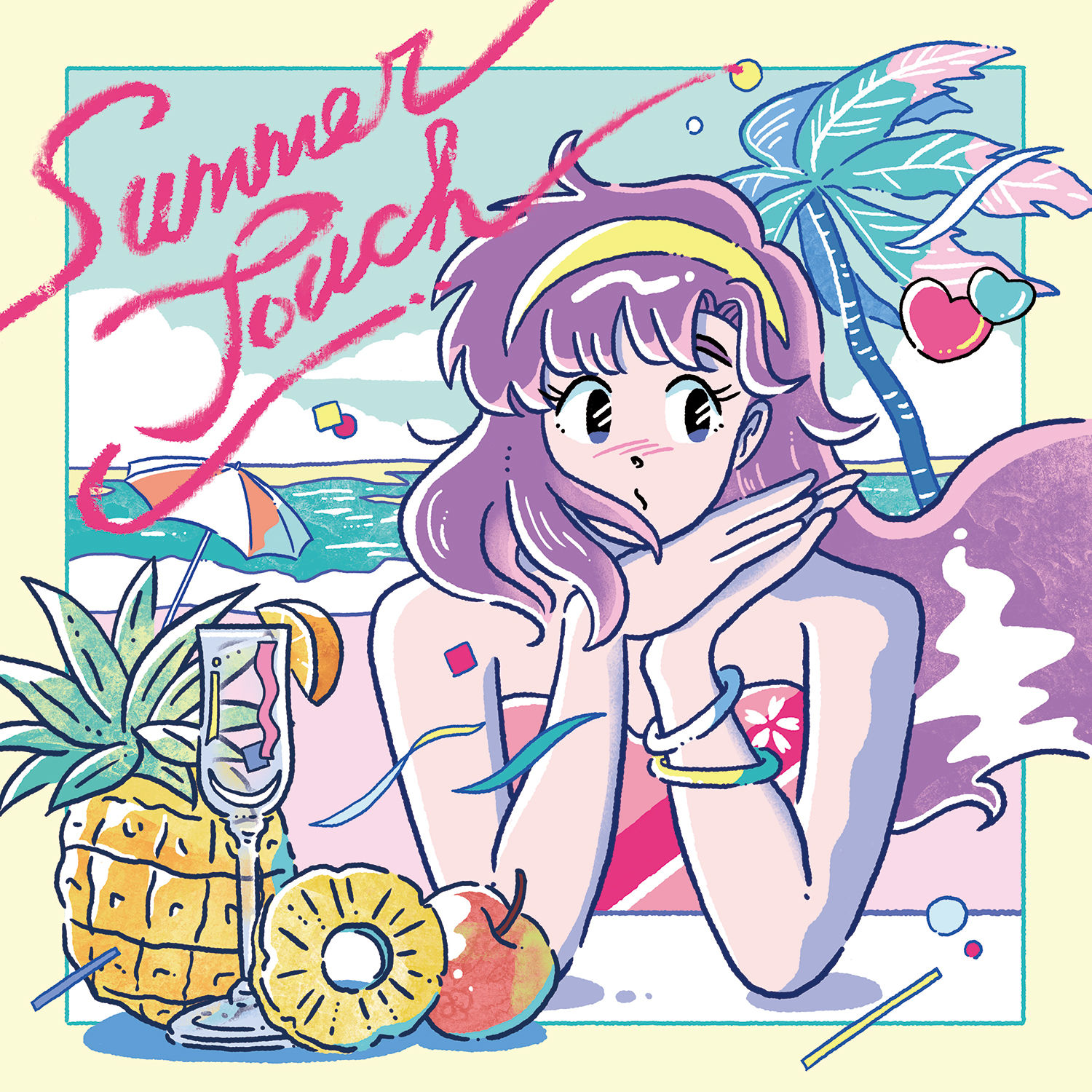

Future funk record sleeves are a distillation of the cutesiness and colour of anime, and of the style and glamour of city pop album art: figures of women dominate the artwork of the genre, glittering like anime heroines but resembling models and idols more than actual superhumans. They’re drawn in a cute fashion, or kawaii style, to use the Japanese word, suiting the sparkliness of the music but in a more hi-fi, less lo-fi way.

Yung Bae’s 2014 Bae LP arguably set the bar, coming with artwork from the American designer Andrew Walker. Since then, the scene has commissioned more and more illustrators to decorate their sleeves, young talents usually based outside of Japan but heavily immersed in the island nation’s pervasive zeitgeist.

So prevalent is the style now, it even has its own dedicated hashtag on Instagram: City Pop, previously a domain of crate digging music geeks. The style also has various other names across East Asia: ‘beyond kawaii’ and ’80s fancy’ in Japan, or ‘kawaii girl’ in Chinese, terminology for an illustration movement propelled in fact by music trends, and one which has been recently celebrated in an exciting new Tokyo art project.

The Menmeiz Movement

Two leading city pop-art illustrators include Namu 13 (Lee Yoon Hwan) and Shiho So, both talents who have made their name illustrating tapes and LPs for Night Tempo, and both of whom have been featured in the recent Menmeiz pop-up in Tokyo, as organised by art guru Saho Maeta.

The Menmeiz pop-up is planned to be the first in a cross-country series aiming to bridge the divide between Japan and its neighbouring countries through the soft power of kawaii, retro-infused art.

“Although 70 years have passed since the end of the Second World War, the political situation between Japan and Korea is not good at all,” Saho tells me by email. “However, young people interact all the time across borders through their shared appreciation for Japanese anime and Korean pop idols.”

“Menmeiz was created to spread kawaii across borders, and make young people connect around the world,” she continues. “The name actually comes from internet slang; menmeiz is a Chinese word meaning ‘kawaii girl’; the origin of the word is the Japanese expression moe, which refers to a strong affection for anime and manga characters.”

Moe can be seen across the works of Shiho (above) and Namu, which Saho sees as indebted to classic anime like Sailor Moon and the works of Rumi Takahashi (Ranma ½). While Shiho was born in Yokohama, Japan, she grew up Taiwanese; Namu meanwhile is Korean, exemplifying the cross-cultural force Saho is hoping to represent.

“In my point of view, kawaii culture is a way of life in Japan,” Shiho tells me in an email discussion with Saho. “Commercials, design and mascot character are all in a cute style, and this is one reason why I came to Japan to work in illustration.”

“By using certain colours close to Japanese comics and a lot of pink, my future funk/vaporwave-like paintings matched easily with the Menmeiz mission,” Namu (below) writes from Seoul. “My art though is generally of a retro mood, as I am greatly influenced by the culture of Japan’s Showa period.”

“Since there are many city pop singers that I want to draw in the future, I hope I can continue my work with Night Tempo.”

Both Shiho and Namu make a perfect match with this music style, and other illustrators are following in their tracks: Mizu Cat for example, or Billie Snippet, the illustrator behind Yung Bae’s latest releases. There are also a large number of city pop-artists who are drawing for Instagram instead of records or cassette tapes, some of whom were also featured in the inaugural Menmeiz event and who we’ve listed below.

Their work ranges across cutesy anime to moodier city pop or neon-spiked vaporwave homages, while the countries they come from include Russia, the Philippines and the US. Japan probably came into their life via the impressive Netflix library of classic Japanese series such as Neon Genesis Evangelion, or from future funk videos online made up of anime clips.

Such influence is more than a one-way street, though, with an effect being felt in Japan’s own illustration and music scenes.

Full-circle kawaii

F*Kaori is a Saitama-based illustrator who caught my eye with art for acts making the city pop of today that is J-pop, and not the vaporwave future funk as you’d expect.

The artist’s cover for Punipunidenki’s release MIRAI addiction is littered with familiar iconography: the Roman bust seen across more surreal vaporwave output, the ‘city skyline by night’ future funk motif, a kawaii girl sitting front and centre. Her cover for a recent Neco Asobi release recalls a city pop aesthetic, meanwhile.

The music though is pop; not the city pop of old, but 21st century Japanese pop in all its cute eccentricity. There are a few retro elements, but in all these musicians are more interested in following the visual vanguard set by Especia, an ahead-of-their-time act who in 2013 were known as vaporwave’s first girl group.

“It’s a very interesting phenomenon,” F*Kaori says when remarking about J-pop’s trend towards odd, retro visuals. “It somehow feels both nostalgic and new. That’s the feeling I got when I first discovered vaporwave.”

According to the artist, the Western appropriation of Japanese culture that led to vaporwave seems to be feeding back into a Japanese culture that’s already been pivoting towards 1980s nostalgia.

“80s nostalgia in Japanese illustration has been around for almost a decade, and I never expected the popularity of this style to last so long,” the artist admits before explaining her thoughts on the style’s enduring popularity.

“In my opinion, it has a dreamy, fairy tale glamorousness to it. It’s the opposite of real.

“It reflects a desire to be immersed in a glam and kawaii world, to never leave a 1980s-based dream.”

I ask F*Kaori why this desire is so strong, and her answer is simple.

“Because reality is painful,” she writes.

The glamour and dreaminess F*Kaori speaks of is why the city pop art-style is more than just repackaged retro. Where future funk arguably trades in pure nostalgia, layering vocals over upbeat rhythms, its branding and look is a more inventive endeavour.

Illustrators around the world are creating a richly textured rendering of a past world that probably never existed, one as joyous and exotic as the one the heroes of Interstella 5555 are taken from, made to become slaves on our humdrum and perhaps painful little planet.

City Pop Art illustrators to follow on Instagram:

Read next: How to design for K-pop

https://www.digitalartsonline.co.uk/features/illustration/from-vaporwave-future-funk-night-tempo-artists-talk-japanese-aesthetics-of-cuteness-city-pop/