Globally, climate change drives a willingness to change lifestyles

This year has seen a huge number of climate-related disasters, from hurricanes to drought and from fires to floods. In the middle of the chaos, the IPCC dropped the first installment of its latest climate report, mapping out how our current choices will shape the planet’s future. All of this would seem to make now a great time to check in on public views of climate change.

Unfortunately, one of the best sources of such check-ins, the Pew Research Center, did its most recent polling on the topic way back in February. The survey of industrialized economies shows a strong and growing worry that climate change will affect people personally and a willingness to make changes to avoid the worst of its impacts. Still, because of the timing, it’s likely that opinion has shifted even further since.

Around the world

Pew surveyed people in 17 different industrialized economies in North America, Europe, and around the Pacific Rim. Obviously left out are the developing economies, which may have the most impact on the trajectory of the future climate, as well as China. But the survey does provide some perspective on public opinion in the countries that are actively pursuing policies intended to address their carbon emissions.

Most of the questions of the survey were done on a four-option scale, with people able to express degrees of agreement including “not at all,” “not very,” “somewhat,” and “very.” Typically, each of the two positive and negative options were grouped together.

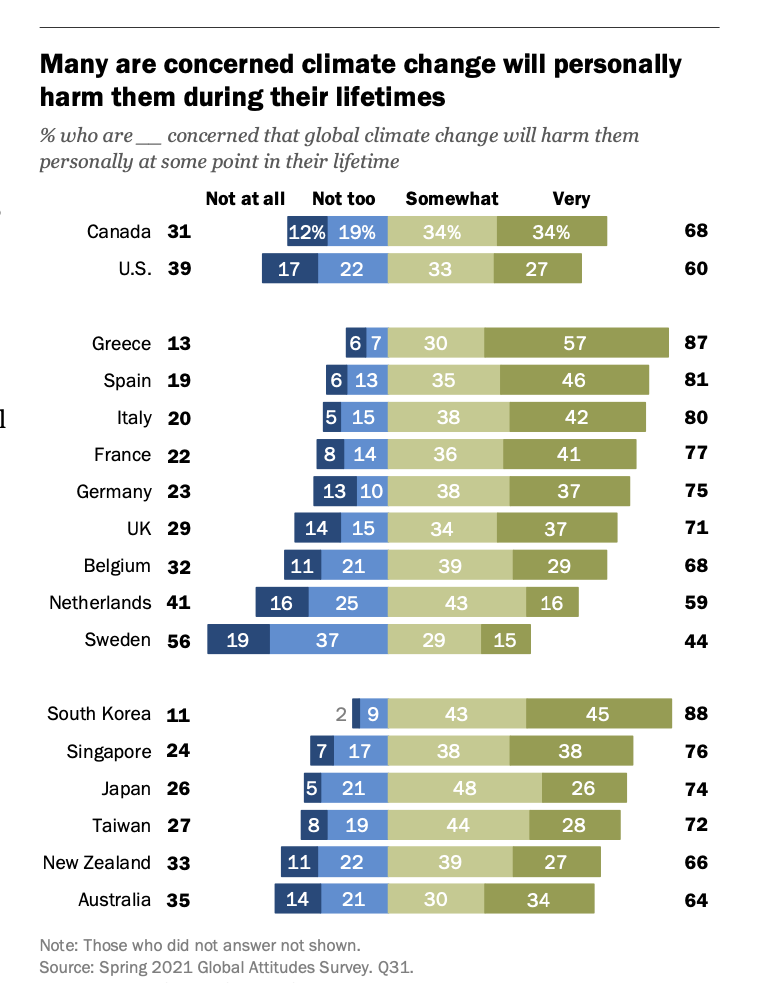

The top line results are pretty clear. Seventy-two percent of those surveyed were somewhat or very concerned that they’ll experience personal harm due to climate change. And an even higher percentage (80 percent) were willing to make changes in their lifestyles to limit the impacts of climate change. On average, however, there are mixed feelings about whether global society is doing everything it should, with only 56 percent feeling that we’re doing a good job and 52 percent lacking confidence that we’ll end up doing as much as we need to.

As you can see from the chart, however, there was considerable variability among the countries. European countries were among the most and least concerned, while the US, Canada, and most Pacific Rim countries fell within these extremes. (The exception being South Korea, which has the most concerned population anywhere.)

In a few countries, Pew had data from five years earlier to compare. This data indicated that Germany saw the highest growth of concern about the climate (up 19 points), and all other EU countries where data was available also saw growth. In contrast, the concern that you’ll be personally affected dropped in the US and Japan, although only slightly.

In all countries but Greece and South Korea, those in the 18-29 age bracket were the most concerned about experiencing personal harm from climate change. The gap between them and the over-65s was highest in Sweden (40 point gap) and New Zealand (31 points). Meanwhile, the gap was lowest in the UK (11 points). Women were about 10 points more likely than men to worry in most countries, as well.

There was also a left/right split, with liberals being more likely to expect to suffer harm. You’d be shocked to hear that the gap was highest in the US, with a 59-point difference between the left and right, followed by Australia, where the gap was 41 points. The smallest difference was seen in South Korea, where only six points separated the left from the right.

Let’s do something

As a result of these worries, most people were somewhat or very willing to make changes in their lives that would help lower carbon emissions. Within the EU nations, Italy saw the greatest willingness (93 percent), and the absolute low was 69 percent, seen in the Netherlands. The US, Canada, and most Pacific Rim countries were somewhere in between these extremes, with the exception of Japan, where only 55 percent were willing to make any changes. As before, the youngest age group was typically more likely to be willing to change, as were those with higher levels of education.

It should be noted that, in many countries, more people were willing to make changes than felt that they were likely to be personally affected, suggesting that a degree of altruism is involved here.

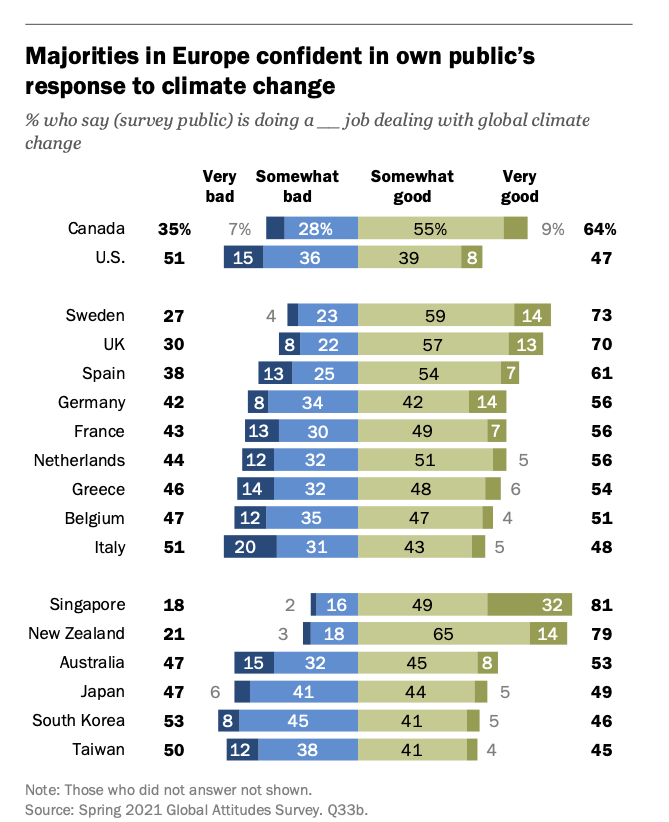

When asked who’s doing a good job of addressing climate change, high marks were generally given to the EU (63 percent felt it was doing well) and the UN (56 percent). Most people surveyed, however, felt that the US wasn’t pulling its weight (61 percent rated its performance as bad), and only 18 percent said that China was doing a good job. The US public had the highest ratings for its performance, but even those were underwater, with only 47 percent suggesting the US was doing a good job of responding to climate change.

As the chart here shows, most countries had a mixed and fairly realistic view of how well their country was doing in addressing climate change. In general, conservatives were more likely to say that their country was doing a good job, with the gaps between conservatives and liberals again being largest in the US and Australia.

While many people were confident that the international community was doing well, most people lacked confidence that it was going to be able to do enough. Four countries—South Korea, Singapore, Germany, and the Netherlands—saw fewer than half those polled doubt our collective ability to get things under control. In every other country, the number was half or more.

Finally, people were asked whether addressing climate change would be a net economic gain, loss, or make little difference. Overall, the plurality were for climate change being neutral, with those thinking it would be a benefit edging out those who expected economic harm. The responses here were complicated. France saw the lowest expectation of benefits but was middle of the pack in terms of expecting harm. Meanwhile, the US had the greatest expectation of harm but was middle of the pack in terms of the size of the population expecting economic gain.

The right time?

A growing number of studies is now indicating that we have to make rapid progress over the next two decades if we still hope to keep atmospheric carbon levels below the point where they’d drive two degrees of warming. The results of the survey show some indications that the public is close to being ready to support tackling that challenge, with younger generations substantially more willing than their elders.

But that readiness isn’t uniform, and there’s some political polarization that may make doing so challenging in countries like the US and Australia.

And again, the polling came before a number of dramatic weather events, some of which have been directly linked to climate change. It’s possible—though sadly not guaranteed—that having more people directly affected by climate change will actually result in an increase of their feeling of risk.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1795300