Here’s one way we know that an EV’s battery will last the car’s lifetime

It’s often said that the easiest way to get people to buy an electric vehicle is to let them test-drive one. But here in the US, EVs only accounted for 3 percent of the 15 million new vehicles sold in 2021. That means there are an awful lot of misconceptions out there when it comes to these newfangled machines.

The top concern is probably range anxiety, a fear that is usually dispelled as someone gets used to waking up to a full battery every morning. I won’t dwell on that today, but the next-most common point of confusion about EVs has to be the traction battery’s longevity, or potential lack thereof.

It’s an understandable concern; many of us are used to using consumer electronic devices powered by rechargable batteries that develop what’s known as “memory.” The effect is caused by repeatedly charging a cell before it has been fully depleted, resulting in the cell “forgetting” that it can deplete itself further. The lithium-ion cells used by EVs aren’t really affected by the memory effect, but they can degrade storage capacity if subjected to too many fast charges or if their thermal management isn’t taken seriously.

The Nissan Leaf bears a lot of responsibility for the idea that EV batteries don’t last. Nissan eschewed liquid cooling for the Leaf’s pack, and the EV first went on sale in model year 2012, so there has been enough time for some early Leafs to lose up to 20 percent of their pack’s storage capacity.

Most EVs aren’t the Nissan Leaf

As it turns out, an EV’s battery pack is subject to a more stringent warranty than the rest of the car—federal law requires automakers to guarantee packs for eight years, or 100,000 miles (160,000 km), at a minimum. And with the exception of Nissan, every EV on sale today features liquid battery cooling as part of the battery management system.

Tesla has been making EVs for long enough that some of its cars have accumulated massive mileages, providing real-world data on degradation over time. EVs from OEMs that are newer to the electrified end of the market instead have to rely on extensive testing programs to determine if their battery packs have what it takes for the long road.

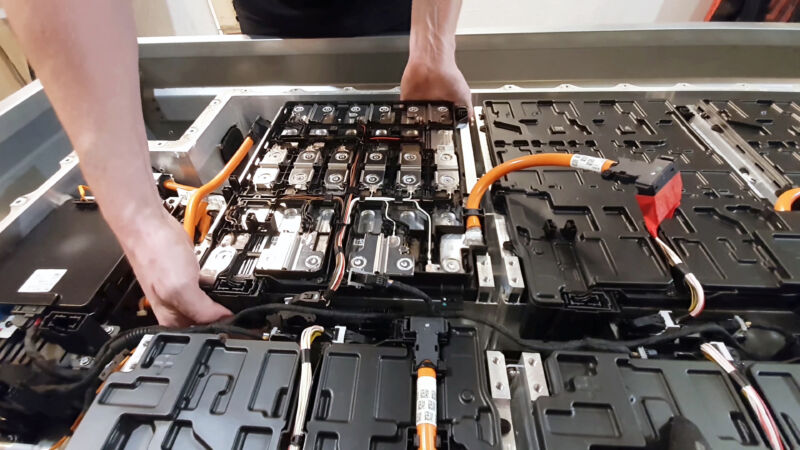

Some of that testing involves actual cells combined into modules, charging and discharging repeatedly over the course of weeks, months, or even years in temperature-controlled test chambers. But simulation can cut costs and development time.

“Often, if you’re testing early on, sometimes you don’t even know what you need to test. But simulation can give you some of these insights from a physics standpoint or from design behavior,” said Pepi Maksimovic, director of application engineering at Ansys, which provides simulation tools to the automotive industry. “There are four primary modes of failure: thermal failure, mechanical failure—because they shake and vibrate and break soldering and so forth—humidity, and dust; and all those effects can and are being modeled,” she told me.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1865557