How a mobile game is reopening a hidden chapter in Taiwan’s history

Thirty years ago, the grandfather of a Taiwanese-American NYPD detective named Danny Lin was thrown off a cliff in Taipei, the capital of Taiwan. The killing took place during what is known today as the White Terror, a 40-year period of violent political suppression and martial law in Taiwan in the middle 20th century. The killer was never identified. Bent on solving his grandfather’s cold case and prompted by the admissions of a mysterious Japanese-Taiwanese woman in a Manhattan ramen restaurant, Lin travels to Taiwan. He knows little about the place, only that, somehow, he must find answers.

Until the last couple of decades, this kind of story, focused on Taiwan’s brutal authoritarianism under military rule, would have been a touchy topic in Taiwan. Today, though, Detective Lin’s saga is the fictional plot behind Unforgivable: Eliza, a popular augmented reality game played on a smartphone, similar to Pokemon Go. The game unfolds as a digitally enhanced tour of New York and then Taipei, with bright manga-esque presentation.

Unforgivable was penned by the Taiwanese-American crime novelist Ed Lin (Incensed, Ghost Month, One Red Bastard) and developed by Allen Yu, the 34-year-old Taiwanese founder of Flushing-based Toii Inc. For these game makers, Lin’s story has been a way to get a new generation to engage with the country’s past. Their efforts parallel a larger trend of younger Taiwanese people exploring their parents’ and grandparents’ lives under military rule.

“People know about this history in Taiwan but don’t really talk about it,” says Yu.

Play your history

In recent years, a number of popular books, films and games have focused on Taiwan’s military period. A whimsical YouTube animation about the 228 Incident, a defining event of the era, has more than two million views. Part of Yu’s own inspiration for Unforgivable comes from Detention, another video game set during the White Terror. Ranked as the second-best PC game of 2017 by Metacritic, Detention boasts more than 200,000 players, according to its developer Red Candle Games. By contrast, Unforgivable counts around 7,000 players between Taiwan, America, and China, says Yu. Rainy Port Keelung, a 2015 game set during the deadly government crackdown that began the White Terror (known as the 228 Incident), has also been commercially successful.

And earlier this year, a mystery title, Devotion, set in ’80s Taiwan, sparked a cross-strait controversy after a meme mocking Chinese President Xi Jinping was discovered hiding in the game. That game was eventually removed from the Steam platform with an apology issued by developer Red Candle Games.

But if Unforgivable is a vehicle through which to learn about past political horrors, it is also meant to encourage a distinct political identity in the present, one firmly grounded on Taiwanese terms. Fifty percent of the game’s funding—one million New Taiwan Dollars, or about $32,300—came from Taiwan’s Ministry of Culture. “We support the game because its story structure describes the background of Taiwan’s democratization,” says Olivia Su, an M.O.C. representative in New York.

Their support parallels larger Taiwanese efforts to strengthen ties between Taiwanese-Americans and Taiwan and to solidify a decidedly Taiwanese identity back home. That’s a political aim of the country’s current administration, headed by Tsai Ing-wen and her Democratic People’s Party (DPP). Her administration has taken a notably more anti-China posture than its predecessor, the Guomindang, or KMT, which, in its previous incarnation, oversaw Taiwan’s dictatorship.

“During KMT rule, we did not have democracy,” says Yu. “My parents would be told, ‘We are all Chinese, we speak Chinese, we are part of China.’ Even today we call ourselves R.O.C., the Republic of China. Everything is so Chinese. But since democracy, after martial law ended, people realized that we are different from China, that we have our own culture.”

Not so long ago, such a statement might have landed Yu in jail.

Growing up alone

Taiwan is an egg-shaped island off Southeast China, north of the Philippines and south of Japan, with a population of 23 million. Slightly bigger than Maryland, it is a rugged place, boasting the highest peaks east of Tibet, verdant and steaming hot. When Portuguese sailors came upon it in the 16th century, they called it Ilha Formosa: beautiful island.

Its modern development has been tumultuous. Beginning in the 17th century, increasingly large groups of Chinese began crossing the Taiwan Strait from Fujian Province. Small conflicts regularly erupted between the settlers and the island’s indigenous population, of which there are several Austronesian tribes. In 1683, the island came under administrative control of the Qing Dynasty, China’s last imperial regime.

The change brought little stability. Intermittent conflict continued amid plagues and occasional uprisings. In 1895, following Japan’s victory in the First Sino-Japanese War, a decade after Taiwan became an official province of the Qing, the emperor ceded Taiwan to Meiji Japan, where it remained a colony for fifty years. Despite the abuses Tokyo may have inflicted, the Japanese laid the commercial and infrastructural foundations for the economic prosperity that would remake the island in the ’80s and ’90s. The northern neighbor also left a significant cultural mark on Taiwan that is still noticeable today.

-

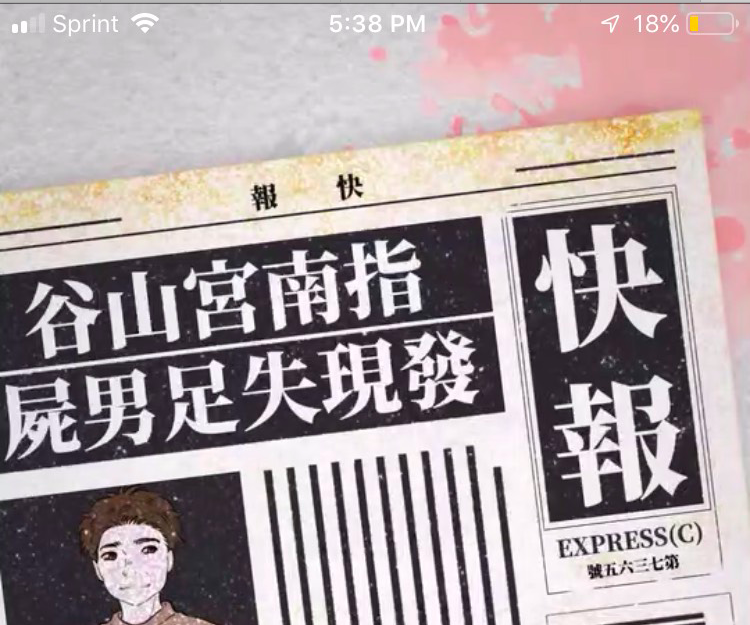

The title screen for Unforgivable.

-

Love to get my news from the magazine “News.”

-

Lookin’ sharp.

-

-

See the world.

After the Japanese defeat in World War II, Taiwan came under the control of the KMT, who declared it part of the Republic of China (ROC). Since 1927, the KMT, led by a general from Zhejiang province named Chiang Kai-shek, had been in bitter conflict with Mao Zedong’s Communists. In 1949, when Mao defeated Chiang’s forces, the KMT fled the mainland to Taiwan. Vowing one day to retake China, Chiang instituted a strict military regime over Taiwan, transforming the island into a police state.

Taiwan was remade ever-ready for war, at the expense of the Taiwanese people. Military service became compulsory. Agricultural and industrial resources were exported to KMT troops across the strait. Civil rights were denied.

The Taiwanese people, who had initially welcomed the KMT as liberators, quickly grew resentful of their exploitative and chaotic rule. In 1947, following a crackdown on an anti-KMT civilian uprising that left more than a thousand dead, Chiang declared martial law, thrusting Taiwan into a suspended period of Orwellian paranoia. That lasted until 1987, twelve years after the Generalissimo’s death, when martial law was finally lifted and democratic reforms began. Remarkably, the small island today counts as one of Asia’s strongest and most open democracies.

With a robust export-based economy, a well-educated populace, sophisticated military, modern infrastructure, and vibrant democracy, Taiwan is by all accounts a resounding developmental success story. Nonetheless, it has been unable to achieve one important milestone: universally recognized sovereignty. Persistent efforts by Beijing, which considers Taiwan a rogue but inseparable piece of its territory, have reduced, through diplomatic and economic pressure, the number of countries recognizing the island’s independence to only seventeen.

Though the US ceded to Beijing’s demands and renounced its recognition in 1979, Washington continues to supply Taipei with critical military support. Beijing’s most serious acts of aggression against Taiwan have all been met with the dispatching of American warships to the Taiwan Strait. Though the People’s Republic of China still claims the right to use force to take Taiwan (a claim it recently reiterated), US support has ensured that the island has remained functionally independent for more than seventy years.

Identity issues

As Taiwan has developed in parallel to the mainland, so too have the cultural and political identities of its citizens. Identity in Taiwan, as intertwined as it is with politics, is very much in flux. That’s a reality reflected in Unforgivable, where characters represent a multitude of backgrounds and ideologies. “It’s kind of like American society. We have different groups, different beliefs,” says Yu. “The most common shared value for Taiwanese identity is that we love democracy and freedom.”

According to an influential annual survey conducted by the Election Studies Center at Taipei’s National Chengchi University, 55.8 percent of respondents identified themselves as only “Taiwanese,” while 37.2 percent chose “Both Taiwanese and Chinese.” The rate of “only Taiwanese” responses has steadily increased since 2007, peaking after the 2014 Sunflower Movement, when mostly student anti-China protesters stormed and occupied the Taiwanese legislature for 23 days.

Such issues often play out in the cultural sphere, sometimes controversially. Spats related to independence and Taiwanese identity have erupted through video game championships, high school choral concerts, a performance by a South Korean teenage popstar, and the Gay Games in Paris, to name a few. At this year’s Golden Horse Awards in Taipei, the Chinese-language Oscars, Taiwanese documentarian Fu Yue sparked an uproar when, in her acceptance speech for best documentary (for a film about the Sunflower Movement), she expressed hope that, “one day our country will be recognized and treated as a truly independent entity.”

Immediately censored in China, the speech soon became a “super topic” on Chinese social network Weibo, with many commentators denouncing the director as deluded. “Every one of these things just adds one more level of humiliation [to Taiwan],” says Andrew Morris, a historian of modern Taiwan at California Polytechnic State University who has studied Taiwanese identity and popular culture. “But I think it’s really hard to sustain a sense of ‘We’re Chinese’ for this long.”

Taboo topics

Allen Yu traces his inspiration for Unforgivable to two Taiwanese political events he attended in New York, (where he studied at NYU’s Game Center) and Washington, DC. At the events, Yu was moved listening to talks from former Taiwanese democracy activists, and he says their tales of selflessness fighting for a higher ideal left a mark on him.

“I think they’re really, really brave people,” he says. “Right now in Taiwan we talk shit—we say anything we like to say—but if these people had said anything bad about the government they might have been kidnapped.” Young Taiwanese individuals nowadays, Yu feels, “take democracy and freedom of speech for granted. We don’t really cherish it.” Though the game is primarily intended for entertainment, Yu hopes it will also help educate the young of the sacrifices made by generations past.

It is a history that, until relatively recently, was too taboo to touch. One of the most sensitive topics was the 1947 anti-KMT uprising that started on February 28, known colloquially as the 228 Incident or the 228 Massacre. Estimates of civilians killed in the ensuing decades-long government crackdown range from 2,000 to 25,000; an official death toll has not been issued. Other details, such as locations of burial sites and which officials ordered what, also remain unknown.

To date, there has been no Truth and Reconciliation-style process in Taiwan. “A lot of the victims and perpetrators are still alive, living together in Taiwan,” says Chieh-Ting Yeh, 36, editor in chief of Ketagalan Media, an online Taiwanese affairs journal. “There’s still a lot of the history that hasn’t been disclosed.”

Instead, much has been swept under the rug. Morris recalls a moment during his time studying Mandarin in the ’90s in Taiwan when, after mentioning the White Terror, his teacher chided him, “We don’t talk about that.” Until recently, Taiwanese school textbooks hardly mentioned the martial law period at all. Certainly during the period itself, it was never mentioned; the education system then focused largely on preparing citizens for their eventual triumphant return to the mainland. “It’s quite funny,” recalls Yu. “When I grew up I learned the geography of China, the history of China, but I didn’t learn about my homeland Taiwan.”

It is only since 2016, with the election of Tsai Ing-wen and her opposition DPP party, that archival documents related to the period have begun being made publicly available; the 2002 Taiwan Archives Act had made it illegal to destroy such documents. The material includes letters written by political prisoners to their loved ones that, for a generation, went unseen. “As soon as I read the first sentence, I cried,” one daughter of an activist who died in prison told the BBC in 2016 after seeing her father’s 1953 letter to her. “I finally had a connection with my father. I realized not only do I have a father, but this father loved me very much.” Many Taiwanese individuals, says Yeh, “still don’t have a sense of closure.”

All of this feeds back into the way that the martial law period is remembered by average Taiwanese today. “There’s a conflation of the Chinese P.R.C. and the Chinese KMT,” says Morris. “It’s almost like, ‘That’s the way the Chinese are. The Chinese who threatened us in the ’90s and 2000s are the same as the Chinese who came here after 1945 and killed all the elites.’”

Playing with the past

-

Life goals.

-

Know your ramen history.

-

That’s probably not good.

-

Personal and political history intertwine.

-

Though most young Taiwanese people will have a passing familiarity with the martial law period, most will not know its particulars, Yu says. “It’s ancient history for the younger generation,” he says. The plot of Unforgivable centers around one such “ancient” moment in history, the 1970 assassination attempt of Chiang Ching-kuo, then-vice premier and Chiang Kai-shek’s son, at the Plaza Hotel in New York. The would-be assassin, a Taiwanese Cornell graduate student named Peter Huang, was thwarted by the quick hand of an American security detail and eventually fled to Europe before returning to Taiwan in the ’90s.

Through a series of events, which speaks to Taiwan’s often-confusing political landscape, Huang went on, in 2000, to be appointed by President Chen Shui-bian as national policy advisor on human rights. He has also headed the Taiwan Association for Human Rights, Amnesty International Taiwan, and the Peacetime Foundation for Taiwan.

Though the game is not intended as a political statement, it has inevitably struck some as one. Contemporary supporters of the KMT, reports Yu, “say this game is crap.” Ted Lin, the crime novelist who wrote its storyline, says he received one angry response from a stranger online who accused the game of being too pro-Japanese. “It’s like, if you don’t think Taiwan is part of China you think it’s Japanese or something,” says Lin. “It’s completely nuts. Why can’t it be its own thing?”

One reaction to Unforgivable that has been surprising to Yu has been its positive reception in China. “We didn’t expect that,” he says. On TapTap, China’s version of Google Play, the game rates an average 9.8 out of 10 stars. “We wonder why [it’s rated so highly], because we talk about the Taiwanese democracy movement and a little bit about Taiwanese identity,” says Yu. “These kinds of political topics are forbidden in China. But I guess that’s what attracts the Chinese players.”

At a recent game show in Tokyo, Yu’s team was approached by Chinese publishers impressed by Unforgivable hoping to collaborate on other games, he adds. Unforgivable players on the mainland, Yu hopes, might notice similarities between repressive KMT agents and contemporary Chinese officials. “They can see how the Taiwanese people fought back,” he says.

On a recent afternoon in Manhattan, Ed Lin and Unforgivable designer Ted Chen sat together at an outdoor table in Bryant Park contemplating the game’s cultural significance. It was an overcast sky with a strengthening wind; a rainstorm was approaching. Chen, bespectacled, with a flat-brim hat and looking ten years younger than his 39 years, mused that Taiwan was becoming more inwardly focused. The popularity of the game, so centered, in a retrospective way, on a heretofore ignored part of Taiwan’s past, reflected that change.

“Young people are not really connected to mainland China because they’re raised in Taiwan,” he said. “All my life is in Taiwan. I received an education there. I did everything in Taiwan.” He had never been to China, he added. Lin, smiley and prone to boisterous, cartoonish laughter, was nodding along intently. The noise of New York auto traffic swirled and waned. “My grandparents,” Chen continued, “always told me, ‘One day we will go back to China. We will be triumphant.’”

Both men looked at each other and laughed.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1490241