How electronic music history was remixed for The Design Museum

Club culture is dead. Long live club culture.

While the recent pandemic may have necessitated the closures of clubs all around the world, it’s not been hard to notice a rise in illegal raves over here in the UK when lockdown got a little too frustrating for some.

That same lockdown has also seen the closure of art venues, temporary in some cases but possibly permanent in others; in tandem with the resurgence of bacchanalian bashes though comes the reopening of London’s Design Museum, which reopens this month with star exhibition Electronic: From Kraftwerk to The Chemical Brothers.

It’s been a long time in the works for curator Jean-Yves Leloup, who helmed the original French version of the show, Expo Electro: De Kraftwerk à Daft Punk, held at the Philharmonie de Paris in April 2019. The French radio DJ and journalist also curated the Design Museum ‘remix’ for British shores, originally meant to open in April 2020 but postponed by the pandemic to the end of July.

“In 2017, the Paris Philharmonie direction team asked me be the curator, and to work on a more aesthetic than historical approach to electronic music,” Jean-Yves tells me in an interview from earlier this month. “Since then, my role was also to find exhibition designers, artists, musicians, DJs, artworks and collectors to fill the whole exhibition. Working or meeting people such as Ralf Hütter from Kraftwerk, Jean-Michel Jarre, Laurent Garnier, Jeff Mills, Underground Resistance team in Detroit, Daft Punk, the exhibition designers and artists 1024 Architecture and many others has been a beautiful and emotional experience for me.

“Gemma Curtin from the Design Museum has been also very important for this new version of the exhibition, gathering many British artists and creators for the London show.”

Assistant curator at the museum Maria McLintock tells us adapting the show from the French to UK version was “so enjoyable,” made possible by a process which saw her and team familiarise themselves with Jean-Yves’s narrative structure of the exhibition.

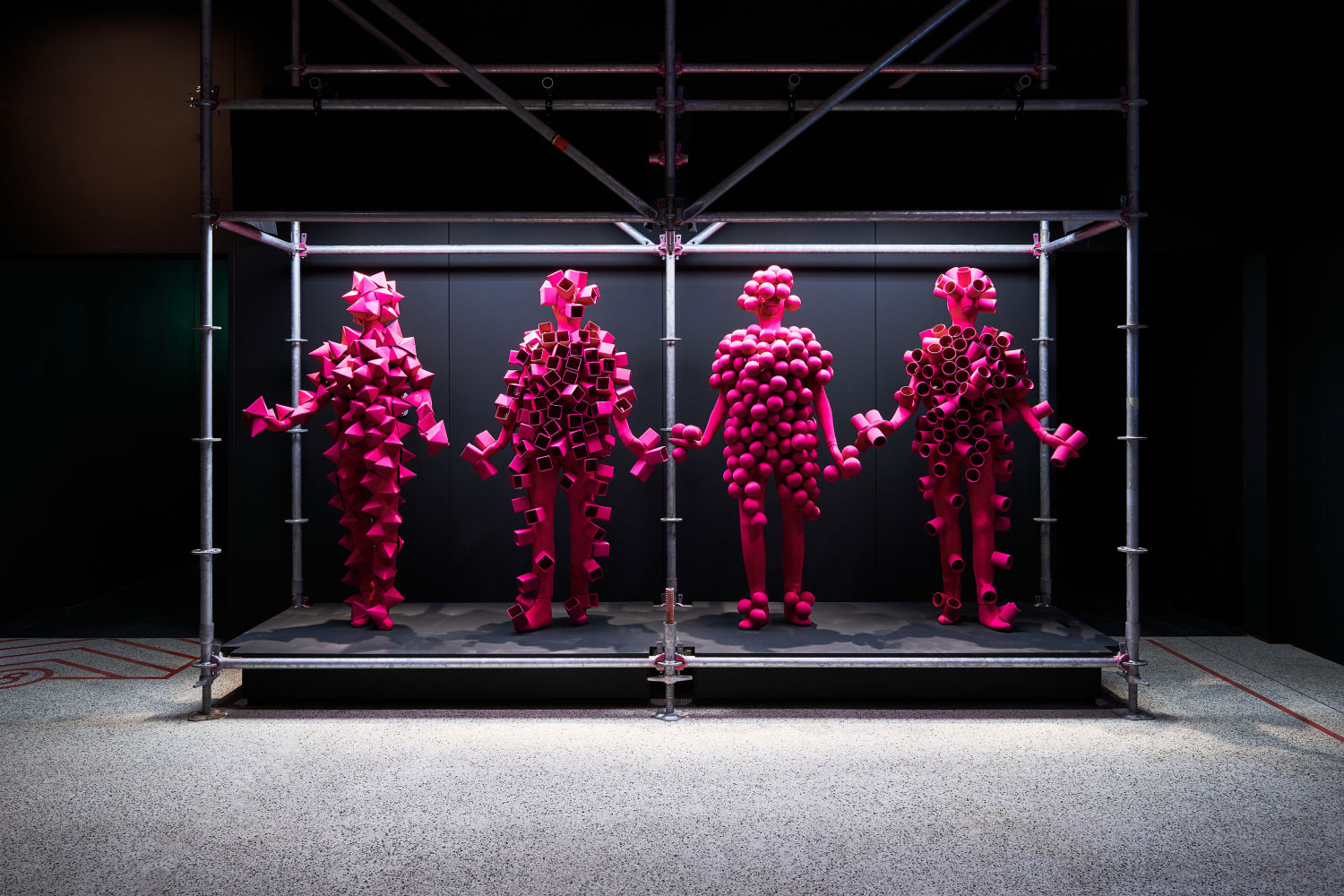

“The show is divided into four sections: ‘Man and Woman Machine’, taken from the Kraftwerk studio album, which explores the technologists and instrumental pioneers who created the tools to produce electronic music; ‘Dancefloor’, celebrating the space of the club as the beating heart of electronic music, influencing a plethora of creative practitioners who are and were part of the scene.

“There’s ‘Mix and Remix’, examining the practice of sampling and assemblage culture so inherent to the genre; and, finally, ‘Utopian Dreams and Ideals’, which shows the political dimension to rave culture.

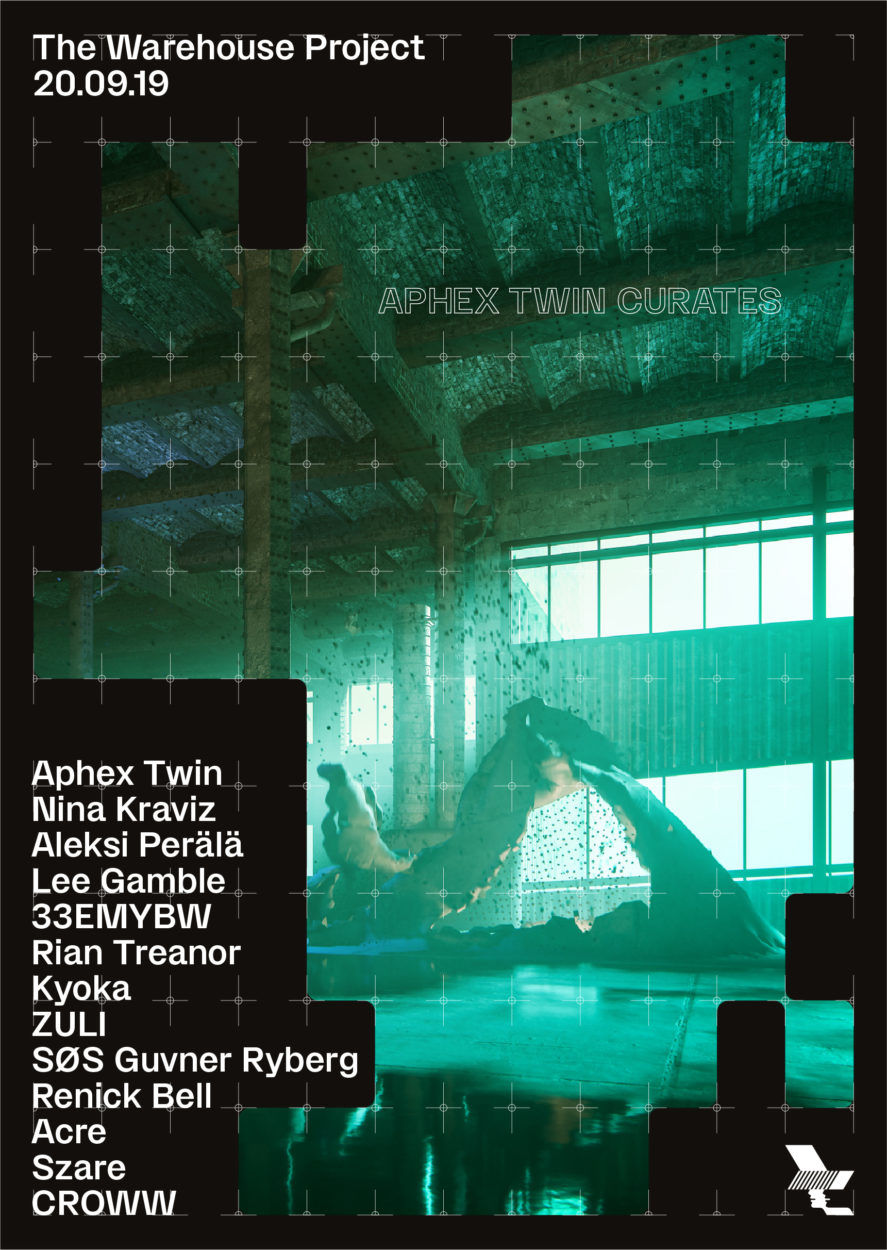

“Once we’d got to grips with the scale of the exhibition,” Maria continues, “our main goal was to draw out design narratives even further, and to insert a more UK focus. On the latter, we’ve added a few new voices and commissions into the structure already there. For example, an installation by Weirdcore, the AV designer who created the visuals for Richard D. James’ (aka Aphex Twin) Collapse tour and EP.

“We also added more archival material to a small section exploring the work of electronic music pioneer Daphne Oram, and included a small film commission about turntablist and composer Shiva Feshareki, who discovered Oram’s Still Point within her archive, and premiered the piece at the Proms.”

The biggest difference between both shows is evident from the titles, where French duo Daft Punk have been replaced by the British twosome of the Chemical Brothers.

“(Daft Punk) did not want to repeat themselves with the same installation presented in Paris, and wanted to concentrate on other projects, so they did not have much time for London,” Jean-Yves reveals. “So we decided to ask the Chemicals and their visual team Smith & Lyall to imagine an installation which would be inspired by their audiovisual shows.”

The audiovisual content is one of the biggest themes of the new show, he tells me, with a stronger emphasis on graphic design and fashion design.

Jean-Yves is also keen to stress that in either guise Electronic has never been a strictly ‘historical’ exhibition.

“We decided to design an exhibition dedicated to electronic dance music, its imagination, philosophy, myths and cultures,” he explains. “(We’ve done this) through its relations with various forms of art and creation: instrument design, graphic design, photography, and digital art.”

Attending a visual preview of the event, we also noticed explorations of dance itself, through the art of street dance, ballet and choreography. A spirit of sci-fi is also present, not just in the famous robots of the Kraftwerk live show but also music videos by Björk, the cyberpunk artwork of Cybotron, and Johanna Vaude’s techno-soundtracked video montages.

Visitors will also find pioneering instruments from the beginning of the 20th century to recent treasures such as a UFO-inspired drum machine by Jeff Mills and Yuri Suzuki.

“Electronic spreads from disco to the current globalisation of DJ culture, (but starts) with the avant-garde, experimental and research studios from 1948 and 1968 which really started the electronic adventure during the post-war period.

“This global aesthetic and cultural approach enabled us to avoid covering each period and scene from dance music history, which would have been impossible.”

“We’ve honed in on five very different places at unique periods of time – Detroit, Chicago, New York, the UK and Berlin,” Maria adds on the remit of the show. “They’re almost incomparable as cities, with their own specific socio-economic landscape and conditions, meaning that different bodies of work have emerged from each location.

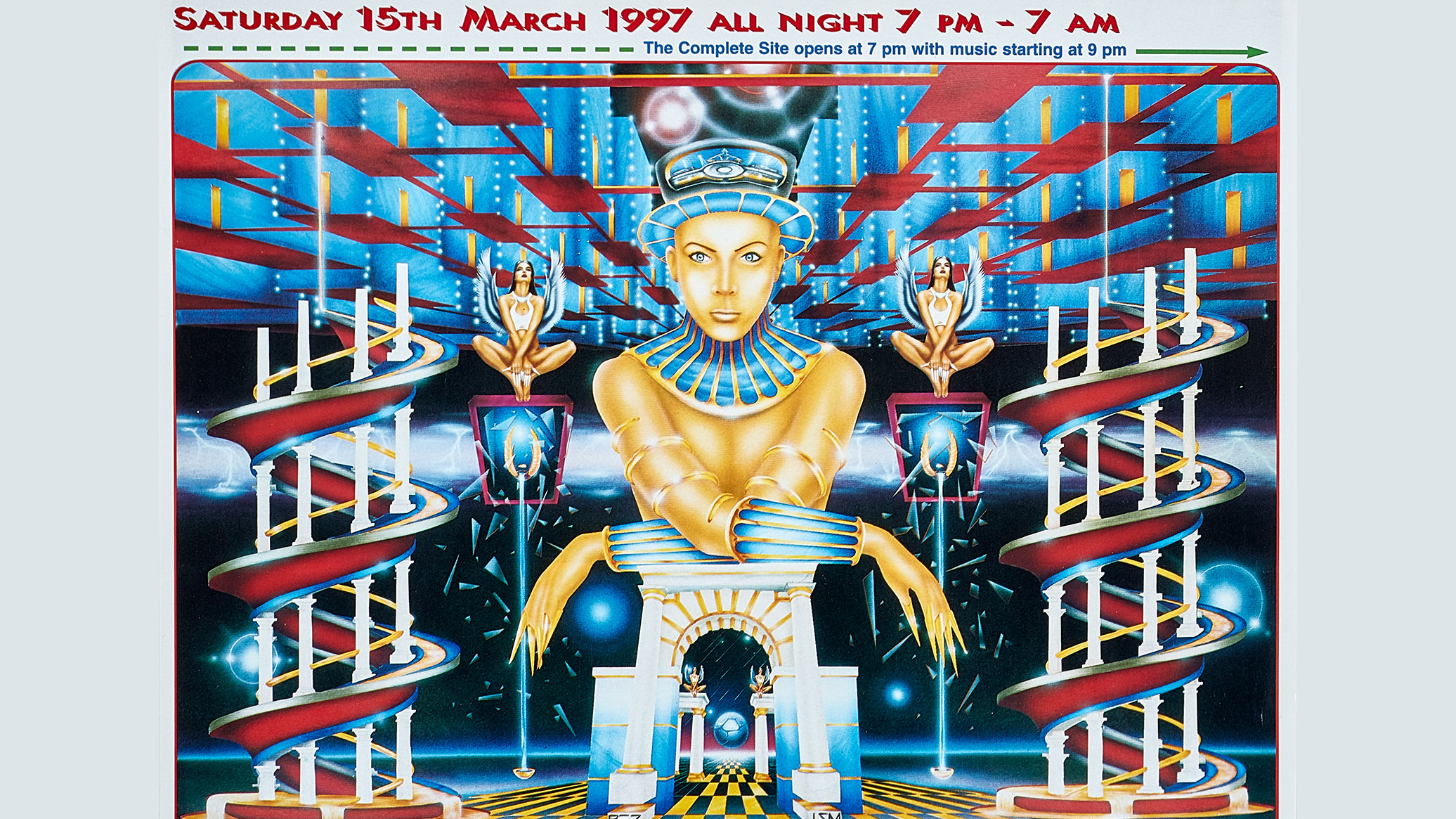

“The Detroit aesthetic was very much about working class African-American and Latinx communities creating another universe outside of the highly industrialised landscape in which they were based. With the UK, we’ve focused on the Second Summer of Love.

“There was no clear or unified ‘aesthetic’ to graphic design then; it was more about assemble and collage (bar the ‘smiley’ which is of course the emblem of the era). What has been most interesting about researching the exhibition is recognising the diversity and aesthetic ambition of each era.”

This worldwide purview incorporates the history of ‘branding’ of dance music releases, mostly with a UK bent as Jean-Yves explains.

“With (the curators), we have decided to concentrate on graphic designers such as Trevor Jackson, Neville Brody, Farrow Design, Designers Republic, Anthony Burrill and more. There are also iconic collaborations between musicians and visual artists, such as Alan Oldham and the Djax-Up-Beats label, Underworld & Tomato, plus the fine aesthetic of electronic music labels such as Warp and Lo Recordings.”

“There is also a very specific selection of rare, beautiful and strange record covers from the 50’s to 70’s, selected by French artist and musician Samon Takahashi. These include some record covers made using the reflective Heliophore printing process, taken from the Prospective 21e siècle Philips series of musique concrète and experimental electronic music.

Prospective 21e Siècle, a collection of avant-garde records (Philips, 1967-1972) https://t.co/KOPpoE7Hui #coverporn pic.twitter.com/OW43GLctov

— Lorenza Venturi (@memoryholes) October 22, 2015

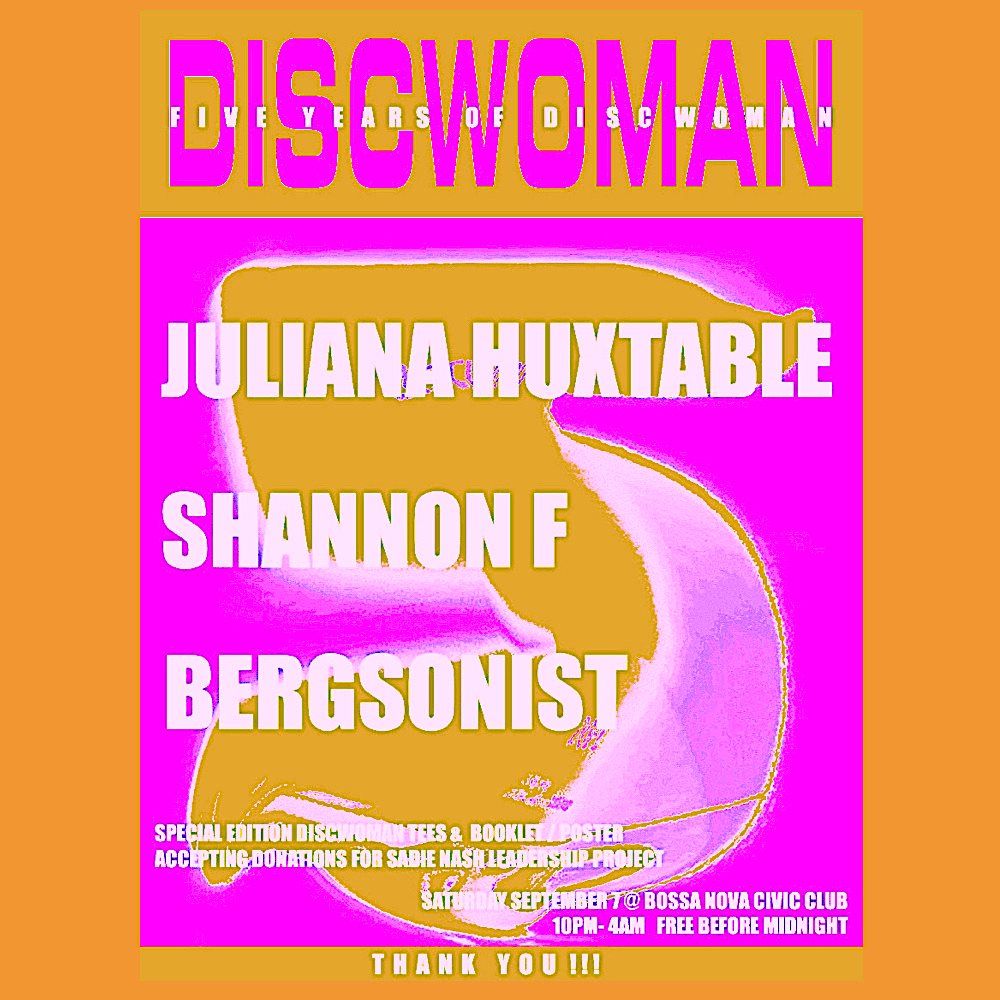

Maria and team also worked with The Wildlife Archive to display collections of flyers from specific moments in UK rave history; for example the raves that exploded around the Second Summer of Love, as well as the LGBTQ scene.

“We have an entire wall of club graphics,” Maria adds, “showing the diversity of material and approaches that venues take to communicating their nights, such as Village Green for Fabric’s early years, and Studio Moross for Warehouse Project.

“We’ve got a series of swatches designed by members of Detroit techno collective Underground Resistance, original posters by Peter Saville for New Order and The Haçienda, and more recent ephemera such as the fifth anniversary zine poster by the wonderful NY-based collective Discwoman. There’s a lot!”

When asked what he’s most proud of from the bountiful Electronic experience, Jean-Yves mentions two large-scale photos by Andreas Gursky of huge dancing crowds.

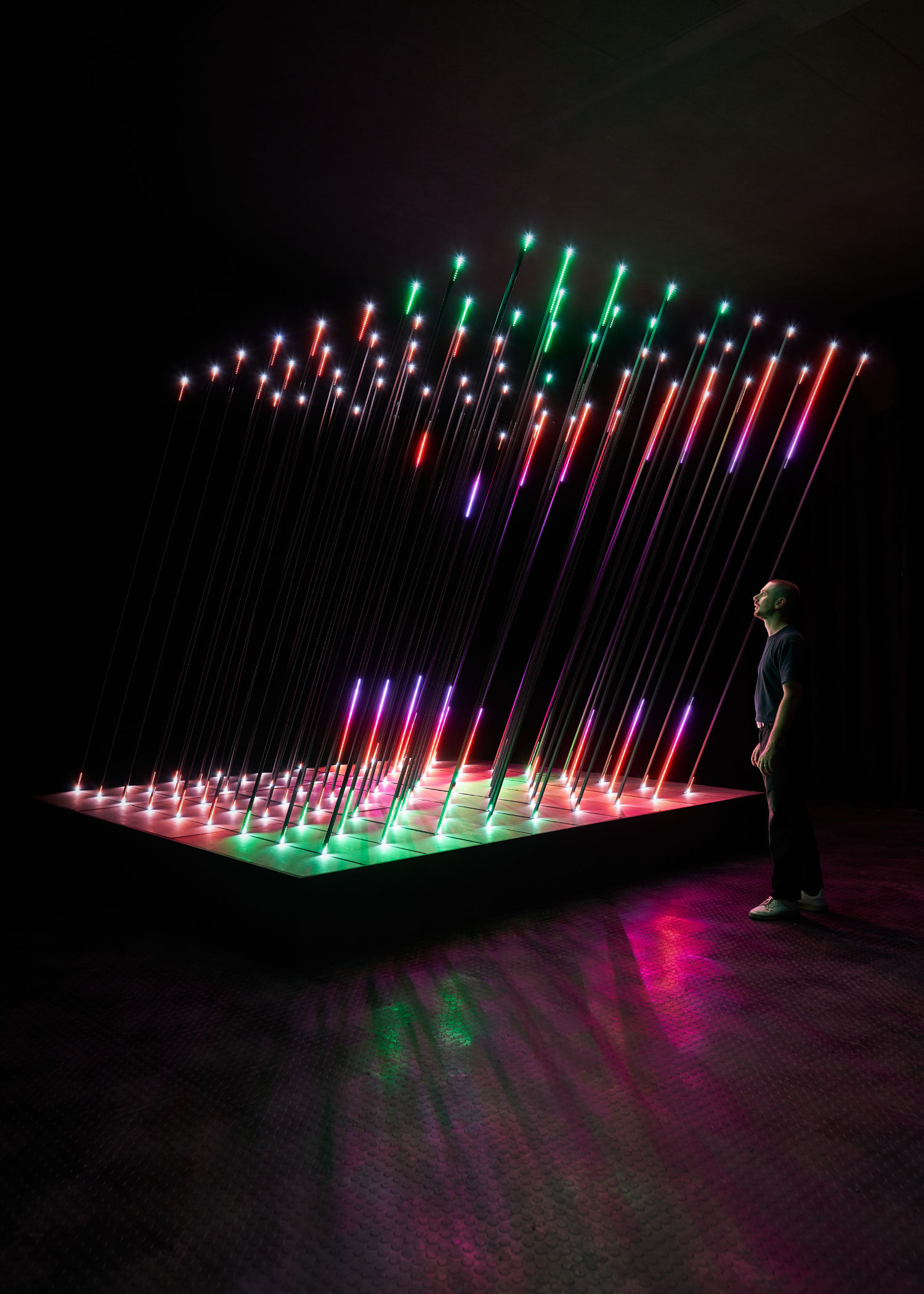

“These anonymous dancers are the real stars of the exhibition!” he stresses. “As an old raver from the 90’s, I am very attached to this theme of the raving crowd. I am also very proud of the core light and music installation, created by 1024 Architecture, using 24,000 thousands led lights, moving in sync with a five hour-long (‘MegaMix’) soundtrack by Laurent Garnier.

“I was also very proud to convince Kraftwerk to participate in the show and also to show my love for the Detroit techno scene, through the visual works of Abdul Haqq and others.”

If had more space and time, Jean-Yves would also have made a few other additions to the show.

“I would have been interested in better covering the South American scene, which could be labelled the ‘NuLatAm Sound’, which mixing its cultural past with electronic production, or today’s very prolific African dance scene.”

“Doing a show about electronic music is comparable to doing a show about sculpture,” says Maria when asked what she would add. “It’s so wide-ranging, diverse and complex in its scope.

“We’re quite aware that there will be narratives we have left out, and the dance community will have lots to say about the decisions made. We absolutely welcome that critique. As Alon Shulman posits in his 2019 book about the second summer of love, there is no one singular history of electronic music.”

Here’s to the Third Summer of Love continuing such a long and illustrious history – just as long everyone stays safe and goes masked in a Daft Punk fashion.

Electronic: From Kraftwerk to The Chemical Brothers will run at the Design Museum in London from 31st July 2020.

Related: Explore the graphic design behind 1990s rave culture

https://www.digitalartsonline.co.uk/features/graphic-design/how-electronic-music-history-was-remixed-for-design-museum/