Huge COVID study finds remdesivir doesn’t work—FDA grants approval anyway

The US Food and Drug Administration on Thursday issued a full approval of the antiviral drug remdesivir for treating COVID-19—just days after a massive global study concluded that the drug provides no benefit.

“The FDA is committed to expediting the development and availability of COVID-19 treatments during this unprecedented public health emergency,” FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn said in a statement. “Today’s approval is supported by data from multiple clinical trials that the agency has rigorously assessed and represents an important scientific milestone in the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Early results

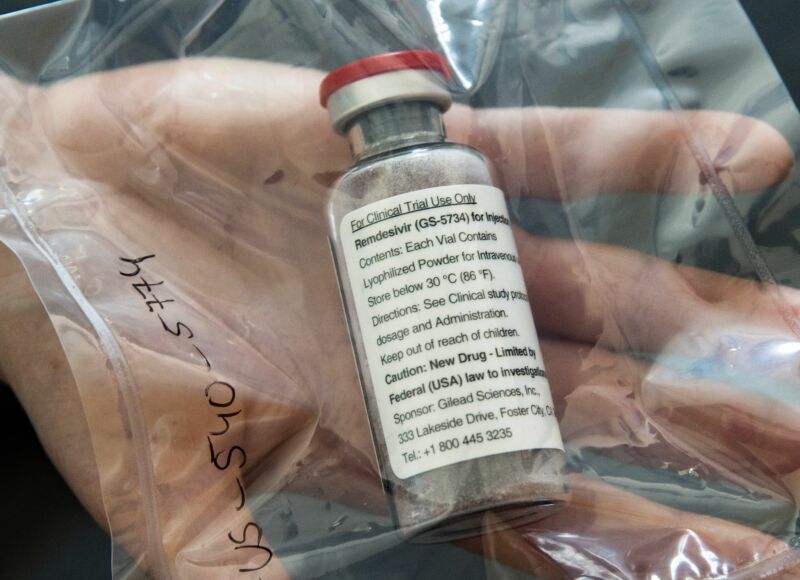

The FDA made its decision based on three clinical trials on remdesivir, a repurposed experimental antiviral drug brand-named Veklury. One was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial run by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. It included 1,062 hospitalized COVID-19 patients, 541 of which received remdesivir. The trial concluded that remdesivir shortened the median recovery time from the infection from 15 days to 10 days. The researchers running the trial defined “recovery” of a patient as either a patient being discharged from the hospital—regardless if the patient still had lingering symptoms that limited activities or required supplemental oxygen to be taken at home—or a patient remaining in the hospital but no longer requiring medical care, such as if they were kept in the hospital for infection-control reasons.

The other two trials the FDA considered were conducted by Gilead, the company that makes remdesivir. One trial looked at about 600 people with moderate cases COVID-19. Patients were split into three groups, each about 200 people—a group that got a 10-day course of remdesivir, a group that got a 5-day course, and a control group that got standard treatments. At day 11 of treatments, the group that had the 5-day course of remdesivir showed a statistically significant improvement in symptom scores compared with the control group. The group that got a 10-day course of remdesivir did not have a statistically significant improvement over the control group, though.

The other Gilead trial looked at 400 patients with severe COVID-19. They were split about evenly into just two groups—a group that got a 5-day course of remdesivir and a group that got a 10-day course. There were no statistically significant differences in recovery or deaths between the two groups.

Missing data

“The [FDA] approval of Veklury marks an important milestone in efforts to help address the pandemic by offering an effective treatment that helps patients recover faster and, in turn, helps preserve scarce healthcare resources,” Barry Zingman said in a press statement released by Gilead. Zingman is a professor at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and one of the researchers who conducted the NIAID trial of remdesivir.

But the FDA’s approval of remdesivir falls on the heels of data form the fourth and largest trial of the drug, and that trial showed no benefit. The data comes from the World Health Organization’s massive Solidarity trial, which set up an international network of trials enrolling nearly 12,000 patients at 500 sites in over 30 countries, testing multiple repurposed therapeutics. Remdesivir was initially developed over a decade ago as a potential treatment for hepatitis C and RSV (respiratory syncytial virus). It has also been tested against Ebola but was beat out by other treatments.

According to preliminary results from the Solidarity trial—reported online last week ahead of its planned publication in the New England Journal of Medicine—remdesivir was given to 2,743 patients, and their outcomes were compared with those of 2,708 patients given standard treatments. Between the two groups, WHO found that remdesivir did not reduce mortality. It also did not change how many patients progressed to needing mechanical ventilation, nor did it change the proportion of patients discharged after seven days of hospitalization.

When the Solidarity trial data was first released, Gilead blasted the results, saying, “The emerging data appear inconsistent with more robust evidence from multiple randomized, controlled studies validating the clinical benefit of [remdesivir].”

Can’t fudge this

But in a press conference Friday, the WHO hit back, arguing that the data was, in fact, more robust that the smaller trials that came before it and should certainly be included in any regulatory or clinical decision.

“It is the largest trial in the world,” WHO’s chief scientist, Soumya Swaminathan noted. And unlike the NIAID study, which used a somewhat subjective clinical scoring system to compare disease progression and a range of definitions for “recovery,” the Solidarity trial compared only clear, indisputable outcomes: mechanical ventilation, discharge from the hospital, and death.

“[Death is] not a soft end point,” Swaminathan said. “You cannot fudge that endpoint.”

Swaminathan also noted that it was clear that the FDA did not have the Solidarity trial data when it made its decision to approve remdesivir. But she emphasized that the WHO had provided that data to Gilead in advance. “They first saw the results on the 23rd of September,” she said, well before it was made public. But “it appears the results were not considered—not provided to the FDA,” she said.

Though the comments suggest the WHO doesn’t support the FDA’s decision to approve remdesivir for treating COVID-19, WHO experts also suggested that the FDA approval may be irrelevant. Instead, expert clinical guidelines for treating patients are what matter most.

“Regulatory authorities may place items on an approved list,” WHO Executive Director Michael Ryan said in the press conference. “That doesn’t necessarily mean that they will be used in any particular practice unless they pass into clinical guidance that’s given to doctors and nurses.”

The WHO noted that it is working on such clinical guidance and treatment recommendations and expects to release them in three to four weeks.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1716889