In the Shadow of Notre Dame

April 17, 2019

John Boardley

The cathedral of Notre Dame has stood at the heart of France and of Paris for the best part of 1,000 years. It watched as Paris rose from a former outpost founded during the Roman Republic to become the biggest city of medieval Europe. And although European printing was born in Germany, it is in France, in the shadow of Notre Dame, that the modern book was born.

What is now the 5th arrondissement on the left bank was once home to one of the greatest centers of book production during the Renaissance. By the close of the fifteenth century, it had become, after Venice, the most prolific printing center in Europe. Running north to south through its heartland was the rue Saint-Jacques, the oldest street in Paris. It is here and in the tangle of streets that surround it, that hundreds of booksellers, illuminators, printers and bookbinders – everyone and anyone involved in the craft of bookmaking – lived.

Among its greatest exports were Books of Hours, small and portable prayer books that were printed in the millions and exported across Europe. In those same streets roman fonts won out over gothic in a war of attrition that had begun with Petrarch, who two centuries before had disparaged gothic script as ‘designed for something other than reading.’

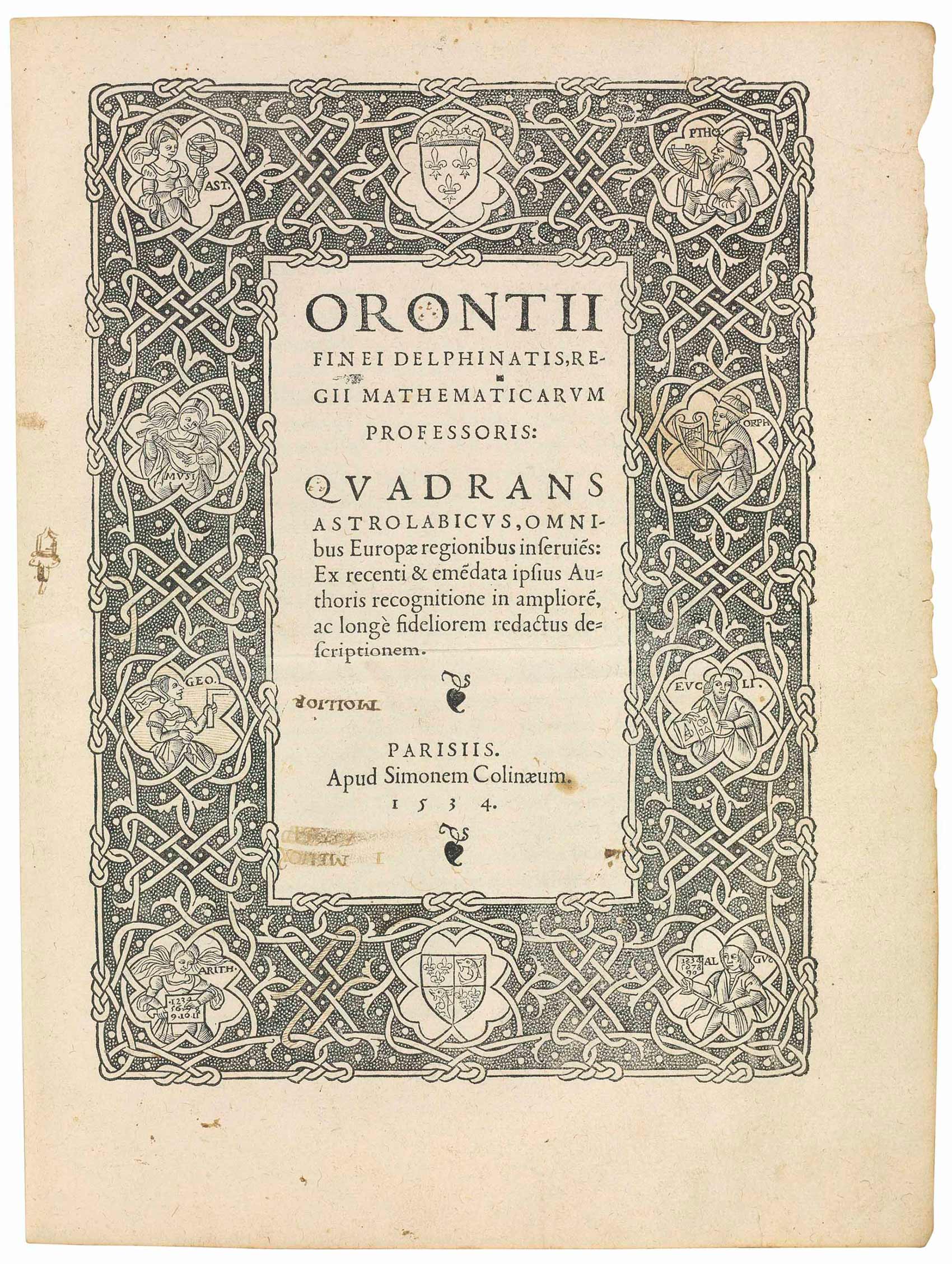

Thielman Kerver (the first to use a roman font in a Book of Hours, c. 1523), Simon de Colines and Geoffroy Tory, Antoine Augereau, Pierre Hautin, Robert Granjon, Simon de Colines and Claude Garamont (or Garamond) are among the great names that helped to established a typographic canon: small format, monochrome, with a single column of text in a legible roman typeface in several sizes; running heads, page numbers and title-pages joined forces to make an eminently readable and visually elegant book. It was in Paris, under the watchful eye of Notre Dame, that the printed book was perfected.

When it comes to rebuilding and recovery, the story of Antoine Vérard, a Parisian printer famed for his Books of Hours, is noteworthy. He had his home and workshop on the Pont Notre-Dame, an impressive wooden bridge, connecting the right bank to the Île de la Cité, on which the cathedral stands.

At 9 o’clock, on the morning of October 28th, 1499, the bridge collapsed taking many of its sixty houses and some of their occupants into the Seine. Among those houses was the home and workshop of Antoine Vérard. Vérard later moved to the rue Saint-Jacques, next to — but not on – the Petit Pont. The bridge and the homes were later rebuilt and Vérard recovered and prospered despite this catastrophic setback. He went on to become one of the foremost printers of his time.