Let’s kick off 2019 by pondering the dismal future prospects for humanity

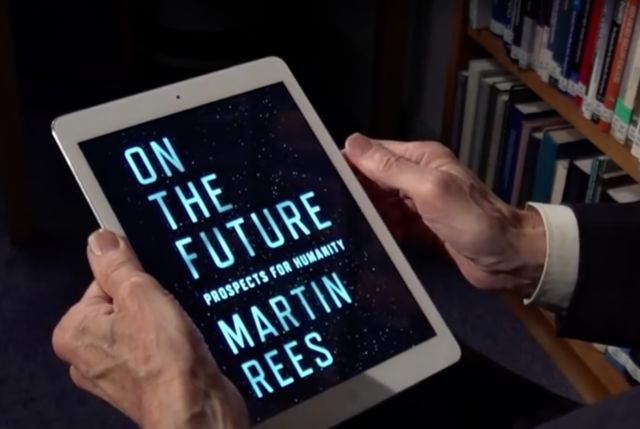

Human kind has long harnessed the fruits of scientific research into revolutionary technologies, with a few tradeoffs along the way. The benefits have generally outweighed the risks. But we are now in an era when the choices we make over the next two decades really could determine the fate of our life here on Earth—a critical tipping point for the human race, if you will. That’s the message from Britain’s Astronomer Royal Lord Martin Rees in his recent book On the Future: Prospects for Humanity, published by Princeton University Press.

While the primary focus of his life has been science, Rees has long been engaged in politics, starting with anti-nuclear weapons campaigns when he was still a student. But that engagement has widened over the last 20 years and his influence has grown. He served as president of the Royal Society and wields real political influence these days in the British Parliament’s House of Lords. (Technically, he is Lord Martin Rees, Baron of Ludlow. But he’ll probably ask you to call him Martin, because he’s chill like that.) “That made me not just a scientist, but an anxious member of the human race,” he said.

It’s a thoughtful anxiety that informs every page of On the Future, as self-proclaimed “techno-optimist” Rees explores the many ways in which humanity’s fate is tightly linked to continued progress in science and technology—and how we choose to wield that knowledge (or not). Ars sat down with Rees in September in London to learn more about his thoughts on our future.

Ars: Your 2003 book, Our Final Century, pondered whether the human race would survive the 21st century given the myriad threats we face. You gave us a 50/50 chance. Are you still as pessimistic about our future?

Rees: I always say I’m a scientific optimist, but a political pessimist, because the science is wonderful. It’s going to have more and more potential for improving health, producing food for a growing population, and hopefully clean energy so we can deal with the problem of CO2 rising. All those things are exciting. But there’s a big gap between the way things could be and the way things are. We know the present-day technology could make a far better life for the world’s bottom billion. That’s not happening. This is a huge collective moral failure. And this makes me pessimistic about whether we can use all these more powerful technologies optimally, without some downside occurring.

Ars: Technology has always been a double-edged sword, hasn’t it? What’s so different about the 21st century?

Rees: The stakes are getting higher because the potential benefits are greater, but so are the downsides. And there’s special responsibility on scientists to try and engage with the public and politicians to ensure that we can benefit from these technologies and minimize the risk of the downsides. That’s crucially important because we don’t want to be Luddites. But I think we do need to worry about all these rapidly advancing technologies, such as cybertech and biotech, where, in our tightly interconnected society, just a few bad actors can have large disruptive, even disastrous, effects. We need to have regulations. I hope political pressure will do this, but that’ll only happen if the public is engaged. And, of course, there is going to be a tension between security and privacy and liberty.

Today, the technology is global with huge commercial implications. A disaster of any kind can’t be restricted to one particular continent. It will spread globally. In the 14th century, when the Black Death happened, about half the population of certain towns died, but the rest went on fatalistically. Today, if there was a similar pandemic, I think once the number of cases overwhelmed hospitals, and once people were aware that they were not going to be able to get the treatment to save their lives, there would be social breakdown. Our society is very fragile and brittle. It would take less than one percent of people to succumb to some fatal disease before there was a real social breakdown.

“It’s very hard to persuade politicians to make a sacrifice now for the benefit of people 50 years from now.”

Ars: It’s often said that climate change is the single biggest threat to humanity.

Rees: For an issue like climate change, the threat is long-term. It’s not immediate. It’s very hard to persuade politicians and the public to make a sacrifice now for the benefit of people 50 years from now in remote parts of the world. If you apply the standard economic discount rate, you’d write off what happens after 2050. If that’s your assumption, then you don’t prioritize climate change. You decide that it’s less important to deal with climate change than to help the world’s poor in more immediate ways.

But if you take a different view and say, “This is the context where we must in effect have a low discount rate, because we should care about the life chances of a baby born now who’ll be alive in the 22nd century. We should be prepared to pay an insurance premium now to remove a potential threat from someone at the end of the century.” That’s what conventional climate policy is aiming to do it, but it only makes sense if you are prepared to take this very long-term view.

Ars: Do you have an alternative vision for a better climate policy that doesn’t require such a long-term focus?

Rees: I’m rather pessimistic about the effectiveness of these current aims to cut CO2 emissions. In my book, I describe one possible win-win situation: promote much more public and private rapid research and development in all forms of clean, carbon-free energy, so that the costs come down more quickly. India, for example, can leapfrog directly from a low energy economy, where hundreds of millions of people are burning wood and dung in stoves in their homes, to some form of clean energy, because it makes more sense economically for them to do so. They won’t need to build coal-fired power stations. This is win-win in the sense that it’s clearly going to be good for India, and also a win for more high-tech countries, which can develop these clean energy technologies.

Ars: Let’s talk a little bit about AI. This was something that your colleague, the late Stephen Hawking, was also concerned about. I’m curious whether you agree with him about the potential dangers of AI going forward.

Rees: I’m not an expert any more than Stephen was, but I do follow the debate. I think it’s remarkable what’s happened in the last few years with AI and generalized machine learning. But it’s a long way from having a machine that can interact with the real world like a human being. The machines can’t sense the real world as adeptly as we can. Some people think we will get to a singularity in 30 years, where machines will take over completely. Others think it’ll never happen.

Some people feel we should regulate AI already in the same way that we regulate biotech. Other people think that in the long run, it’s human stupidity, not artificial intelligence, that should be our primary concern. I’m somewhere in between. One reason why people are over-worried because they use an analogy of Darwinian evolution. There’s an advantage in being intelligent. There’s also an advantage in being aggressive. For these machines, it’s not at all clear that they would be aggressive. So whether they would actually take over in the kind of way that’s envisaged in some science fiction movies, it’s not at all clear.

Ars: Is there any realm where you think AI is likely to be highly beneficial, with fewer potential drawbacks?

Rees: I do think that it’s in space that AI has its greatest upsides and fewest downsides. It’s very expensive to send people into space. At the moment machines aren’t as alert. The Curiosity Rover that’s trundling across Mars now may miss things that a human geologist would see immediately. But that may change, and soon we’d be able to send robots to explore the planets in our solar system, and have large robotic fabricators to build huge structures in space. So the case is getting weaker all the time for sending people into space.

Ars: And yet many people dream of going to space, perhaps colonizing the moon or Mars, or venturing beyond our solar system one day.

Some pioneers will go into space, and perhaps go to Mars. But I think this will best be done by the private companies, like Elon Musk’s SpaceX and Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin. Privately funded projects can accept higher risks than NASA can impose on publicly funded civilians. The shuttle was launched 135 times and it failed just twice—a less than two percent failure rate. Many test pilots, mountaineers ,and adventurers are happy to accept those risks. But those two failures of the Shuttle were a national trauma in America, which led to a delay in the program and a futile attempt to cut the risk further. So I think the best opportunity is for the private sector to do this in a high-risk way.

“The idea that we can escape Earth’s problems by going to Mars is a dangerous delusion.”

Space tourism is the wrong phrase to use. It should be space adventure, because it’s not going to be routine, it’s going to be risky, maybe even one way tickets. Musk has said himself that he hopes to die on Mars, but not on impact. In 40 year’s time, this might be realistic. The respect in which I don’t agree with Musk, or indeed with Stephen, who said the same thing, is in thinking there will be mass emigration. I think Mars will just be a place for the pioneers and adventurers, just like the summit of Everest and the South Pole. The idea that we can escape Earth’s problems by going to Mars is a dangerous delusion. We’ve got to solve them here, because dealing with climate change is a doddle compared to terraforming Mars.

I hope that there will be some regulation and constraints on the use of AI and biotech here on Earth. But a group of pioneers living on Mars will be away from all the regulators. Moreover, we’re well-adapted to the Earth, but they will not be at all well-adapted to Mars. So they will have every incentive and every opportunity to use all the techniques of genetic modification and cyber-technology and so forth to adapt themselves to this hostile environment.

I think that’s where the first post-humans will emerge. If it turns out that, as Ray Kurzweil says, you can download human intelligence into some electronic machine, those machines won’t want an atmosphere. They may prefer zero g. So they will leave the planet and because they’re near-immortal, they’re not going to be deterred by an interstellar journey. So one scenario, for the far future, is that there will be electronic intelligences, which will eventually spread from our solar system and far beyond. I think it could well be that the instigators of those will be future pioneers on Mars. They’ll be cosmically important even though we might think they’re crazy.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1434411