Library’s prized Galileo manuscript turns out to be a clever forgery

Since 1938, one of the most prized items in the University of Michigan library’s collection has been a rare manuscript page allegedly written by Galileo. But after an internal investigation, the library’s curators have concluded that the manuscript is in fact a fake—and most likely executed by a well-known 20th-century forger. The curators were tipped off about the forgery by Georgia State historian Nick Wilding, who became suspicious of the manuscript’s authenticity while working on a biography of Galileo.

“It was pretty gut-wrenching when we first learned our Galileo was not actually a Galileo,” Donna L. Hayward, interim dean of the University of Michigan’s libraries, told The New York Times. Nonetheless, the library opted for transparency and publicly announced the forgery. “To sweep it under the rug is counter to what we stand for,” Hayward said.

The single-leaf manuscript in question purported to be a draft of an August 24, 1609, letter that Galileo wrote to the doge of Venice describing his observations with a telescope (occhiale) he had constructed. (The final letter is housed in the State Archives in Venice.) Galileo first heard of a marvelous new instrument for “seeing faraway things as though nearby” in a letter from a colleague named Paolo Sarpi, who had witnessed a demonstration in Venice. Unsatisfied with the performance of the available instruments, Galileo built his own, even learning to grind his own lenses to improve the optics.

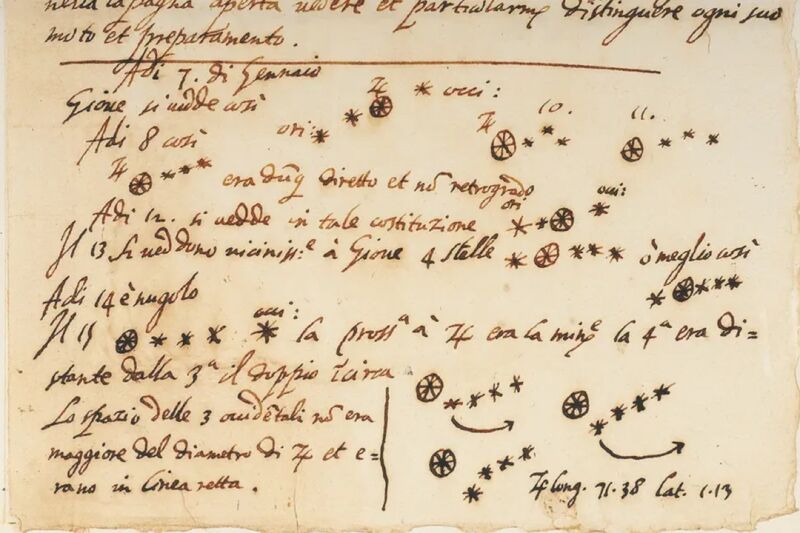

The first object Galileo studied was the Moon, toward the end of 1609, and then Jupiter when it was closest to the Earth and hence the brightest object in the evening sky (apart from the Moon itself, of course). He noted on January 7, 1610, that Jupiter appeared to have three fixed stars nearby. Intrigued, he returned to looking at the planet the following night, expecting the then-retrograde body to have moved from east to west, leaving the three little stars behind. Instead, Jupiter seemed to have moved to the east.

Puzzled by the planet’s behavior, Galileo returned to the formation repeatedly, observing several key details. First, the little stars never left Jupiter but appeared to be carried along with the planet. Second, as they were carried along, they changed their position with respect to each other and to Jupiter. Finally, he discovered a fourth little star.

Galileo concluded that the objects were not fixed stars but small moons that revolved around the planet. And if Jupiter had four orbiting moons, then the Earth could not be the fixed center of the universe, as most scholars believed at the time. This observation provided the first empirical support for Copernicus’ theory that the Sun rather than the Earth was at the center of the Solar System. Galileo published this groundbreaking observation in his book Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Messenger) in March 1610.

The top half of the library’s manuscript is the alleged draft of Galileo’s letter to the doge of Venice, dated circa August 9, 1609. The bottom half, supposedly written months later, contains a series of “doodles” that depict Jupiter’s moons—once thought to be original notes from Galileo’s observations in January 1610.

Enter Nick Wilding, who has exposed Galileo-related forgeries in the past, most notably a copy of Sidereus Nuncius in the possession of a New York City rare-book dealer. This copy supposedly included an inscription by Galileo, as well as five of his watercolors of the Moon. Although the paper and binding of Sidereus appeared to be genuine, Wilding eventually found that it, along with another copy listed in the 2005 Sotheby’s catalog, both had an identical blotch on the title page that could be traced back to a 1964 facsimile edition. “If [the forger] hadn’t been greedy enough to make two copies, I wouldn’t have been able to prove the forgery,” Wilding told The New York Times in 2012.

When he turned his attention to the Michigan manuscript, Wilding thought that some of the letter forms and word choices seemed odd, and the ink on the top and bottom halves seemed very similar, despite those sections having been (allegedly) written months apart. So he emailed the library requesting information about the document’s provenance, as well as an image of its watermark.

The University of Michigan library acquired the manuscript in 1938 as a bequest from a Detroit businessman named Tracy McGregor. McGregor had purchased the manuscript at auction four years earlier; it had previously belonged to a wealthy collector named Roderick Terry. According to the auction catalog, the manuscript had been authenticated by an archbishop of Pisa named Cardinal Pietro Maffi. The cardinal had two other documents in his collection purportedly signed by Galileo, and Maffi used those documents as comparisons.

But Wilding found that there is no record of the Michigan manuscript in Italian archives. Furthermore, Maffi had acquired the two documents he used for comparison from the notorious early 20th-century counterfeiter Tobia Nicotra, calling the cardinal’s authentication into question.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1874592