Link between herpesviruses and giant viruses no longer missing

Double-stranded DNA viruses come in two main flavors, classified by their shapes. One contains large and giant DNA viruses that attack complex cells but also includes some viruses that are much smaller and infect bacteria. These viruses are shaped like soccer balls. The other flavor has tails and primarily infects bacteria and archaea but also contains the herpesvirus family, which infects animals.

The disparate properties of these viruses have raised some questions that have been plaguing virologists: Where did herpesviruses come from? And how are the large and giant DNA viruses related to the smaller viruses within their realm?

Tara Oceans is “an international, multidisciplinary project to assess the complexity of ocean life across comprehensive taxonomic and spatial scales.” Researchers with the project sail around all five oceans and two seas (the Red and the Mediterranean), sampling plankton to try to understand the ocean ecosystem. In new work reported in Nature, a team pulled plankton from the sunlit oceans (it’s a technical term: only down to 200 meters below the surface, where light penetrates and photosynthesis happens). They surveyed all the planktonic DNA viruses by comparing a single hallmark gene among them.

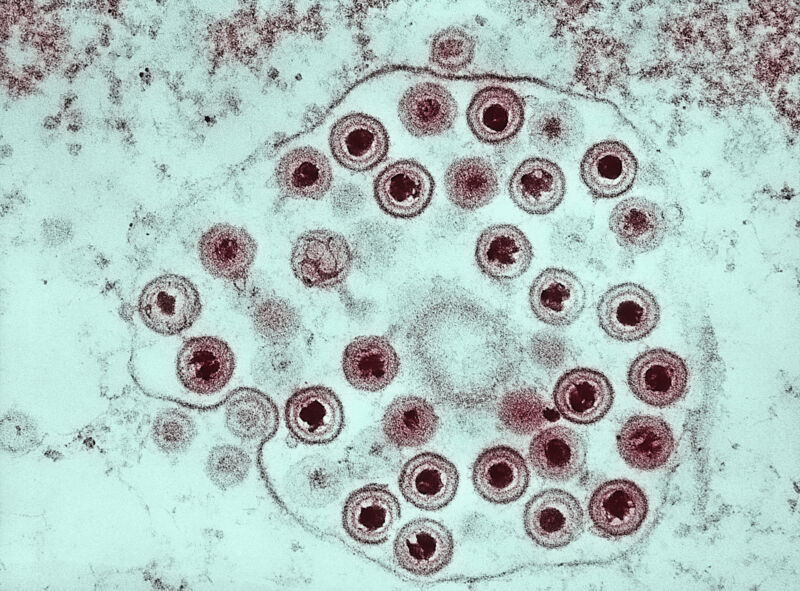

This analysis revealed a new phylum of DNA viruses that are shaped like herpesviruses and infect eukaryotes but share a key enzyme with large and giant viruses. The scientists named the phylum mirusviruses, for the Latin word mirus, meaning surprising or strange.

They identified seven different clades of mirusviruses and found them all over the globe. Three were found exclusively in the Arctic Ocean, while only one was specific to temperate water. And even though they were only just identified, it appears that mirusviruses are among the most abundant eukaryotic viruses in the sunlit oceans. They are also super active within the plankton they infect, indicating that they likely play key roles in the marine ecosystem.

The two realms of DNA viruses bridged by mirusviruses—one containing the giant viruses, and the other containing herpesviruses—are ancient lineages. So the paths that they all took to get where they are today are not yet clear. The similar shape of mirusviruses and herpesviruses suggests that these eukaryotic viruses share a common ancestor. The authors speculate that the shared enzyme was transferred between a giant virus and this common ancestor, although they don’t know which lineage had it first or which way it got transferred. At some later point, herpesviruses lost the gene through reductive evolution. Then somewhere along the way, they gained the ability to infect animals. Lucky us.

Nature, 2023. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-05962-4

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1934235