Lost and found: Codebreakers decipher 50+ letters of Mary, Queen of Scots

An international team of code-breakers has successfully cracked the cipher of over 50 mysterious letters unearthed in French archives. The team discovered that the letters had been written by Mary, Queen of Scots, to trusted allies during her imprisonment in England by Queen Elizabeth I (her cousin)—and most were previously unknown to historians. The team described in a new paper published in the journal Cryptologia how they broke Mary’s cipher, then decoded and translated several of the letters. The publication coincides with the anniversary of Mary’s execution on February 8, 1587.

“This is a truly exciting discovery,” said co-author George Lasry, a computer scientist and cryptographer in Israel. “Mary, Queen of Scots, has left an extensive corpus of letters held in various archives. There was prior evidence, however, that other letters from Mary Stuart were missing from those collections, such as those referenced in other sources but not found elsewhere. The letters we have deciphered are most likely part of this lost secret correspondence.” Lasry is part of the multi-disciplinary DECRYPT Project devoted to mapping, digitizing, transcribing, and deciphering historical ciphers.

Mary sought to protect her most private letters from being intercepted and read by hostile parties. For instance, she engaged in what’s known as “letter-locking,” a common practice at the time to protect private letters from prying eyes. As we’ve reported previously, Jana Dambrogio, a conservator at MIT Libraries, coined the term “letter-locking” after discovering such letters while a fellow at the Vatican Secret Archives in 2000.

Those “locked” Vatican letters dated back to the 15th and 16th centuries, and they featured strange slits and corners that had been sliced off. Dambrogio realized that the letters had originally been folded in an ingenious manner, essentially “locked” by inserting a slice of the paper into a slit, then sealing it with wax. It would not have been possible to open the letter without ripping that slice of paper—providing evidence that the letter had been tampered with.

Queen Elizabeth I, Catherine de Medici, Machiavelli, Galileo Galilei, John Donne, and Marie Antoinette are among the famous personages known to have employed letter-locking for their correspondence. There are hundreds of letter-locking techniques like “butterfly locks,” a simple triangular fold-and-tuck, and an ingenious method known as the “dagger-trap,” which incorporates a booby-trap disguised as another, simpler type of letter lock. Mary, Queen of Scots, used an intricate spiral letter-lock for her final letter (to King Henri III of France) on the eve of her execution for treason in February 1587. A 1574 letter from Mary also used a variant of the spiral lock.

Mary was well-trained in the art of cipher by her mother, Marie de Guise, from a very young age. The substantial collection of her letters that are housed in various archives contains tantalizing references to other missing letters. John Bossy, author of Under the Molehill: An Elizabethan Spy Story (2002), suggested that these missing letters might have been written in cipher to Mary’s extensive network of associates and allies—a network that was fatally compromised around mid-1583 by Sir Francis Walsingham (Elizabeth I’s spymaster), eventually leading to Mary’s trial and execution for treason. Like many before him, Bossy assumed those letters had been lost.

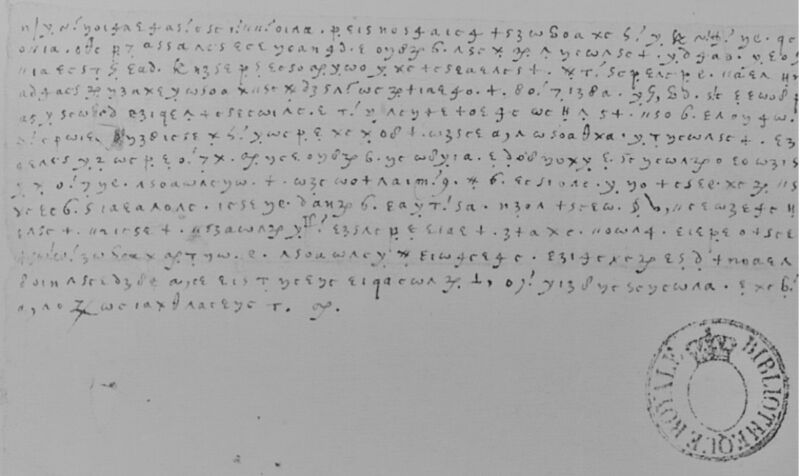

Enter Lasry and his fellow code-breaking enthusiasts: physicist and patents expert Satoshi Tomokiyo and pianist and music professor Norbert Biermann. As part of DECRYPT, they were scouring various archives for documents encrypted with ciphers, particularly documents that had not yet been attributed. They stumbled upon several collections at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France’s online archives, identifying 57 documents fully written in cipher. Other items in the collection dated from the 1520s and 1530s and were primarily concerned with “Italian affairs.” None of the text in the letters was written in clear language, so it wasn’t possible to determine who wrote them without first deciphering them.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1915179