Mysterious benefactor returns Charles Darwin’s missing notebooks after 20 years

Twenty years ago, two small notebooks written by 19th-century naturalist Charles Darwin mysteriously disappeared from the archives of Cambridge University Library. One of the notebooks even contains Darwin’s iconic 1837 sketch of the so-called “Tree of Life.” After multiple searches and a public appeal, the notebooks have finally been returned by an anonymous person.

“My sense of relief at the notebooks’ safe return is profound and almost impossible to adequately express,” said Cambridge University Librarian Jessica Gardner in a statement. “Along with so many others all across the world, I was heartbroken to learn of their loss, and my joy at their return is immense. They may be tiny, just the size of postcards, but the notebooks’ impact on the history of science and their importance to our world-class collections here cannot be overstated.”

Darwin famously set sail on the HMS Beagle on December 27, 1831, as the ship’s naturalist. The expedition’s purpose was to chart the coastline of South America, and Darwin’s job was to collect and record specimens as well as investigate local geography at the various landing sites. He dutifully recorded all his observations in his notebooks and shipped many of his finds back to England so other scientists could study them. Originally slated to last for two years, the voyage took nearly five years to complete.

The Beagle finally anchored at Falmouth, Cornwall, on October 2, 1836. After a brief stop to visit family, Darwin returned to Cambridge, eager to take part in the study and cataloging of all the specimens he had collected. By the following March, Darwin learned enough to openly speculate in his Red Notebook about the possibility of one species changing into another.

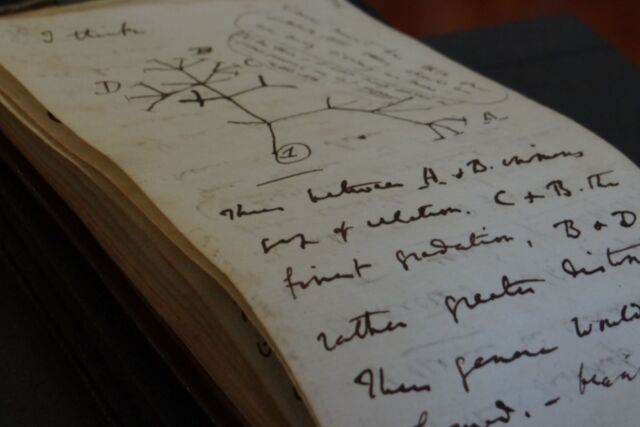

In mid-July 1837, Darwin wrote down his ideas about life span and variation across generations of animals. He believed his ideas could explain all the diversity he had observed, particularly among the tortoises, mockingbirds, and rheas he recorded in the Galapagos Islands. That’s when he sketched the famous “Tree of Life” in his “B” notebook, showing a genealogical branching of a single evolutionary tree and concluding that “it is absurd to talk of one animal being higher than another.” He would publish the fully developed version of that tree over 20 years later in The Origin of Species.

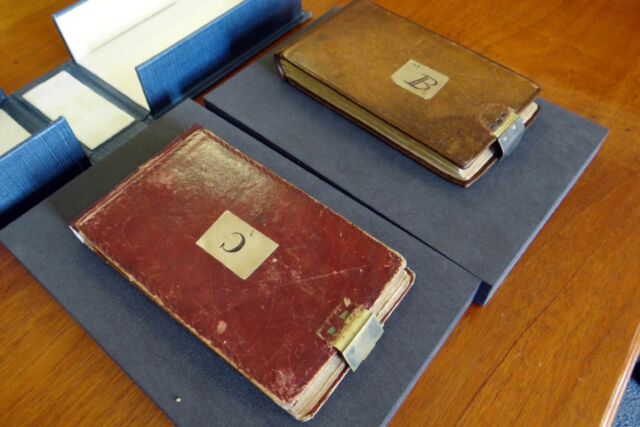

The “B” notebook with its “Tree of Life” sketch was stored along with Darwin’s “C” notebook in a blue box about the size of a paperback in the archives of the Cambridge University Library. Together, they are known as the “Transmutation Notebooks,” and while they are priceless artifacts, their value is estimated at several million British pounds. The university boasts the largest and most significant collection of Darwin material in the world, including the naturalist’s personal library.

In September 2000, the notebooks were removed from the Special Collections Strong Rooms to be photographed. However, in January 2001, the librarians found that the small blue box and the priceless notebooks within were missing. Initially, the assumption was that the notebooks had been misplaced. Librarians conducted searches over the next two decades, but the Special Collections room alone holds millions of documents.

Gardner came on board in 2017 and launched a new exhaustive search in 2020. Numerous experts combed through the entire Darwin Archive and even made fingertip examinations. Still, the notebooks could not be found. Gardner and several other experts concluded that the notebooks had likely been stolen.

So the Cambridge University Library launched a public appeal for the return of the notebooks on November 24, 2020, coinciding with the celebration of Evolution Day—the publication anniversary of On the Origin of Species in 1859. The Cambridgeshire Police were notified, and the notebooks were listed in the national Art Loss Register, as well as on PSYCHE, an Interpol database of stolen artworks. This also ensured that the international book trade could keep an eye out for the missing notebooks, given that such unique and valuable items could never be sold on the open market.

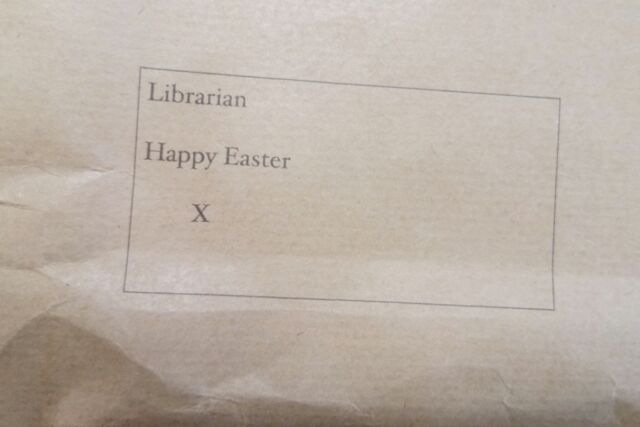

That appeal paid off 15 months later when a bright pink gift bag appeared in a public area just outside Gardner’s office. Inside was a plain brown envelope simply addressed “Librarian: Happy Easter.” The envelope contained the blue archive box with both notebooks inside, wrapped in plastic film and still intact. To celebrate their return, the two notebooks will be featured in an upcoming free exhibition, Darwin in Conversation, opening at the library on July 9. The exhibit will be transferred to the New York Public Library in 2023.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1845873