NASA scientist on 2023 temperatures: “We’re frankly astonished”

Earlier this week, the European Union’s Earth science team came out with its analysis of 2023’s global temperatures, finding it was the warmest year on record to date. In an era of global warming, that’s not especially surprising. What was unusual was how 2023 set its record—every month from June on coming in far above any equivalent month in the past—and the size of the gap between 2023 and any previous year on record.

The Copernicus dataset used for that analysis isn’t the only one of the sort, and on Friday, Berkeley Earth, NASA, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration all released equivalent reports. And all of them largely agree with the EU’s: 2023 was a record, and an unusual one at that. So unusual that NASA’s chief climate scientist, Gavin Schmidt, introduced his look at 2023 by saying, “We’re frankly astonished.”

Despite the overlaps with the earlier analysis, each of the three new ones adds some details that flesh out what made last year so unusual.

Each of the three analyses uses slightly different methods to do things like fill in areas of the globe where records are sparse, and uses a different baseline. Berkeley Earth was the only team to do a comparison with pre-industrial temperatures, using a baseline of the 1850–1900 temperatures. Its analysis suggests that this is the first year to finish over 1.5° C above preindustrial temperatures.

Most countries have committed to an attempt to keep temperatures from consistently coming in above that point. So, at one year, we’re far from consistently failing our goals. But there’s every reason to expect that we’re going to see several more years exceeding this point before the decade is out. And that clearly means we have a very short timeframe before we get carbon emissions to drop, or we’ll commit to facing a difficult struggle to get temperatures back under this threshold by the end of the century.

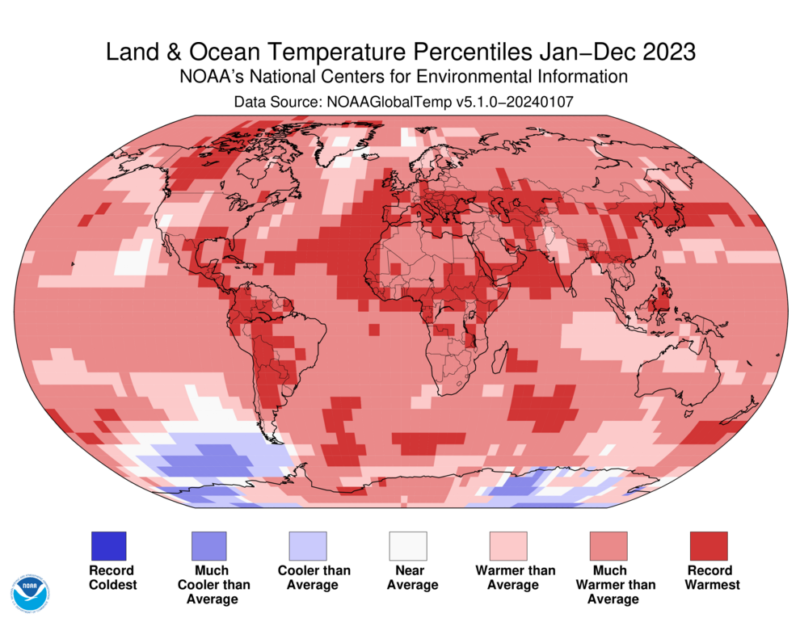

Berkeley Earth also noted that the warming was extremely widespread. It estimates that nearly a third of the Earth’s population lived in a region that set a local heat record. And 77 nations saw 2023 set a national record.

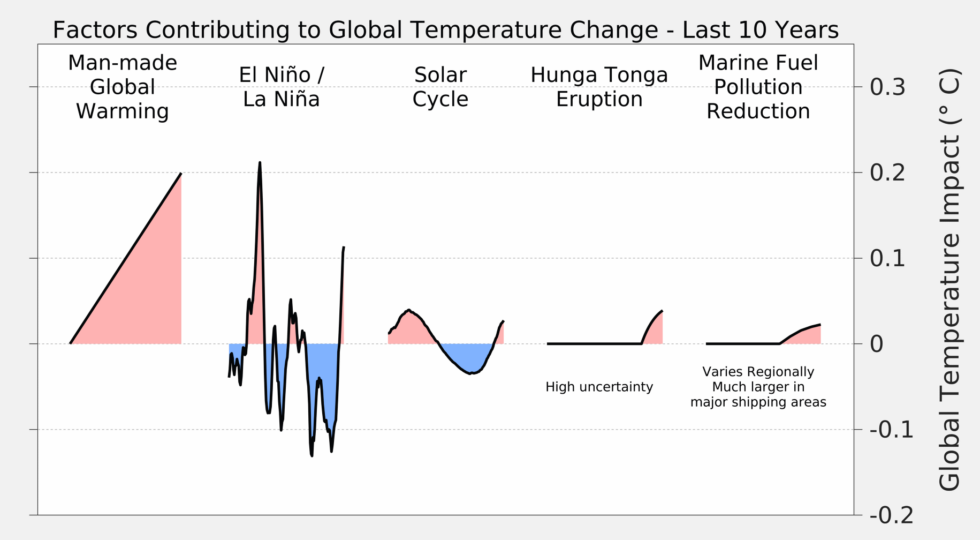

The Berkeley team also had a nice graph laying out the influences of different factors on recent warming. Greenhouse gases are obviously the strongest and most consistent factor, but there are weaker short-term influences as well, such as the El Niño/La Niña oscillation and the solar cycle. Berkeley Earth and EU’s Copernicus also noted that an international agreement caused sulfur emissions from shipping to drop by about 85 percent in 2020, which would reduce the amount of sunlight scattered back out into space. Finally, like the EU team, they note the Hunga Tonga eruption.

An El Niño unlike any other

A shift from La Niña to El Niño conditions in the late spring is highlighted by everyone looking at this year, as El Niños tend to drive global temperatures upward. While it has the potential to develop into a strong El Niño in 2024, at the moment, it’s pretty mild. So why are we seeing record temperatures?

We’re not entirely sure. “The El Niño we’ve seen is not an exceptional one,” said NASA’s Schmidt. So, he reasoned, “Either this El Niño is different from all of them… or there are other factors going on.” But he was at a bit of a loss to identify the factors. He said that typically, there are a limited number of stories that you keep choosing from in order to explain a given year’s behavior. But, for 2023, none of them really fit.

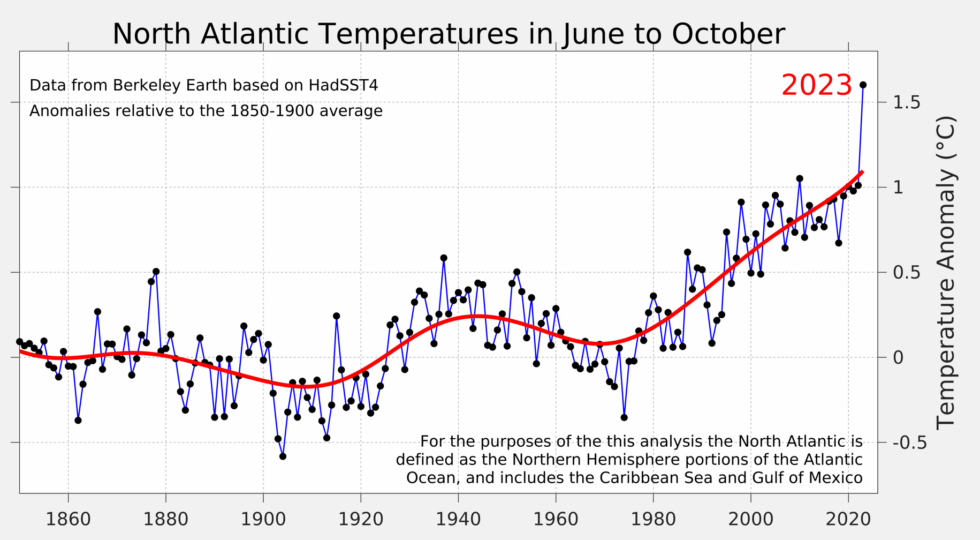

Berkeley Earth had a great example of it in its graph of North Atlantic sea surface temperatures, which have been rising slowly for decades, until 2023 saw record temperatures with a freakishly large gap compared to anything previously on record. There’s nothing especially obvious to explain that.

Lurking in the background of all of this is climate scientist James Hansen’s argument that we’re about to enter a new regime of global warming, where temperatures increase at a much faster pace than they have until now. Most climate scientists don’t see compelling evidence for that yet. And, with El Niño conditions likely to prevail for much of 2024, we can expect a very hot year again, regardless of changing trends. So, it may take several more years to determine if 2023 was a one-off freak or a sign of new trends.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1995689