Nasal COVID vaccine blows clinical trial, flinging researchers back to the lab

The nasal version of the Oxford/AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine failed an early-stage clinical trial, dashing hopes for better infection prevention and forcing researchers to re-think the design.

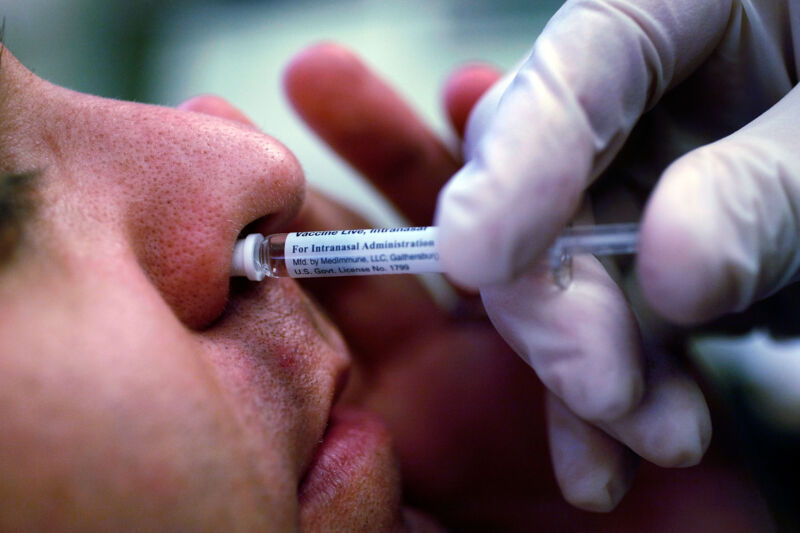

Many experts have hyped the potential of nasal COVID-19 vaccines. They argue that snorting the shots could encrust the nasal mucous membranes with snotty antibodies—namely IgA—and other immune defenses that could blow away SARS-CoV-2 virus particles before they have the chance to cause an infection. Currently, the shots given intramuscularly in arms provide robust systemic immune responses that prevent severe disease and death but spur relatively weak antibody levels on mucous membranes and, relatedly, don’t always prevent infection.

Researchers at the University of Oxford hoped to easily adapt their existing COVID-19 vaccine for such an infection-blasting schnoz spritz. The Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine is a viral vector-based design, using a weakened, benign virus to carry the genetic code of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to human cells. The benign virus, in this case, is an adenovirus, a type best known for causing mild cold-like illnesses in humans, though the specific virus used in the vaccine was isolated from chimpanzees. (This vaccine has not been authorized in the US but is used in dozens of countries worldwide.)

Researchers got a whiff of success in pre-clinical trials involving non-human primates, which developed strong mucosal antibody responses after nasal administration. But their hopes were snuffed out in the early clinical trial, the results of which were published this week in the journal eBioMedicine.

Disappointing data

In the 42-person, phase I trial, nasal administration of the vaccine produced only modest mucosal antibody responses in just a few participants and also spurred weaker systemic responses than the intramuscular shots. The trial included 30 people who had not been vaccinated previously and 12 vaccinated people who tested the nasal vaccine as a booster. The nasal administration blew it on both accounts. The only good news was that no safety issues were found.

But, in yet more disappointing findings, the vaccine also appeared ineffective at preventing COVID-19. The small, early-stage trial was not designed to assess effectiveness, but the researchers note that 7 of the 42 participants reported SARS-CoV-2 infections after the nasal vaccination. This is “discouraging for the prospect of robust and durable protection,” the Oxford researchers concluded in the published study.

In a press release, the trial’s lead researcher, Sandy Douglas, at the Jenner Institute, University of Oxford, put it softly, saying, “The nasal spray did not perform as well in this study as we had hoped.”

Douglas noted that data from researchers in China suggests more success with a similar vaccine administered with a nebulizer device, though the Oxford researchers noted they wanted to aim for the more practical administration of a nose squirt. Douglas also noted that an intranasal vaccine had earned approval in India, but clinical trial data on that vaccine has not yet been published.

Overall, Douglas suggested that his research team will go back to the design stage, such as coming up with new formulations that may help the vaccine better glom onto the nares and respiratory tract to avoid slipping down into the stomach. The researchers also wondered if the adenovirus vector, originally wiped from chimpanzees, may simply be bad at infecting human snouts. They also pondered trying larger doses.

While the trial results are a setback to the cause, outside experts urged researchers to not give up. The outcome is “disappointing,” infectious disease expert Andrew Freedman of Cardiff University said in a statement. “It should not, however, deter further work to develop more effective intranasal vaccines to protect against COVID-19 and other respiratory infections.”

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1889484