New iodine-based plasma thruster tested in orbit

Most people are probably familiar with iodine through its role as a disinfectant. But if you stayed awake through high school chemistry, then you may have seen a demonstration where powdered iodine was heated. Because its melting and boiling points are very close together at atmospheric pressures, iodine will readily form a purple gas when heated. At lower pressures, it’ll go directly from solid to gas, a process called sublimation.

That, as it turns out, could make it the perfect fuel for a form of highly efficient spacecraft propulsion hardware called ion thrusters. While it has been considered a promising candidate for a while, a commercial company called ThrustMe is now reporting that it has demonstrated an iodine-powered ion thruster in space for the first time.

Ion power

Rockets rely on chemical reactions to expel a large mass of material as quickly as possible, allowing them to generate enough thrust to lift something into space. But that isn’t the most efficient way to generate thrust—we end up trading efficiency in order to get the rapid expulsion needed to overcome gravity. Once in space, that need for speed goes away; we can use more efficient means of expelling material, since a slower rate of acceleration is acceptable for shifting things between different orbits.

The current efficiency champion is the ion thruster, which has now been used on a number of spacecraft. It works by using electricity (typically generated by solar panels) to strip an electron off a neutral atom, creating an ion. An electrified grid then uses electromagnetic interactions to expel these from the spacecraft at high speed, creating thrust. The ions end up being expelled at speeds that can be an order of magnitude higher than a chemical propellant can produce.

Only a relatively small amount of material can be accelerated at once, so this can’t generate anything close to the amount of thrust produced in a short period of time by a chemical rocket. But it uses far less material to produce the same amount of thrust and, given enough time, can easily produce an equivalent acceleration. Put differently, if you can be patient about your acceleration, an ion engine can do the equivalent amount in a form that uses less mass and less space. And those are two very important considerations in spacecraft.

Critical to making this work on a spacecraft’s energy budget is a material that can be ionized without requiring much energy. Right now, the material of choice is xenon, a gas that’s easy to ionize and resides several rows down the periodic table, meaning that each of its ions is relatively heavy. But xenon has its downsides. It’s relatively rare (it’s only one part per 10 million in our atmosphere) and must be stored in high-pressure containers, which cancel out some of the weight savings.

Enter iodine

Iodine seems like an ideal alternative. It’s right next to xenon on the periodic table and normally exists as a molecule composed of two iodine atoms, so it has the potential to produce more thrust per item expelled. It’s even easier to ionize than xenon, taking 10 percent less energy to lose an electron. And, unlike xenon, it happily exists as a solid under relevant conditions, making storage far simpler. Just a bit of heating will convert it to the gas needed for the ion engine to work.

The big downside is that it’s corrosive, which forced ThrustMe to use ceramics for most of the material that it would come into contact with.

The thruster design included a fuel reservoir filled with solid iodine that could be heated with resistance heaters powered by solar panels. The iodine itself was inside a porous aluminum oxide material that kept it from fragmenting from the vibrations it experienced during launch (the aluminum oxide is 95 percent open space, so it didn’t subtract much fuel storage). The tank is connected to an ionization chamber via a small tube; when the system was cooled after use, enough iodine would solidify in this tube to seal off the fuel from the outside world.

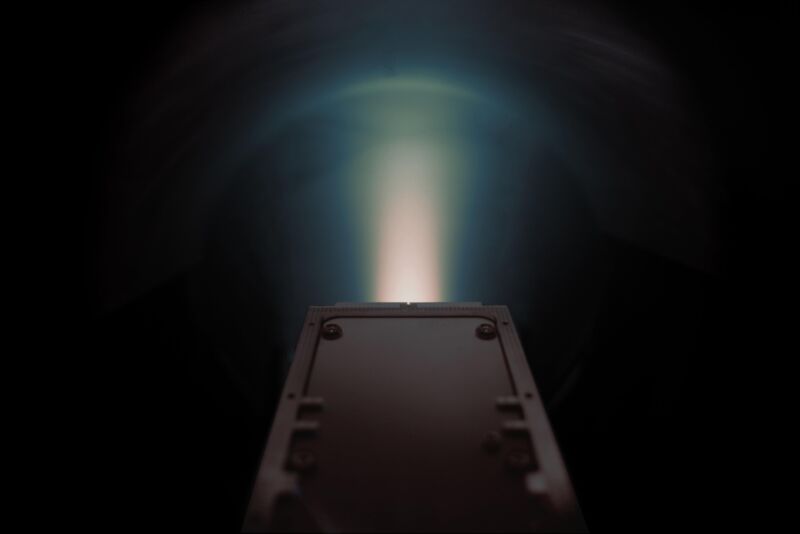

Once in the ionization chamber, the iodine gas is bombarded with electrons, which will knock other electrons off, creating a plasma. The nearby electric grid then accelerated the positive ions out of this plasma, creating thrust. Electrons were extracted from the plasma and injected into the ion beam to keep everything electrically neutral.

Heat extractors were attached to the electronics and the walls of the iodine tube, with the heat recirculated into the iodine fuel while the thruster was firing. This kept the power requirements for vaporizing the iodine down to a single Watt once the thruster reached steady state.

The whole setup was incredibly compact, taking up about the same amount of space as a 10 centimeter-per-side cube, and weighed only 1.2 kilograms. And, by some measures, it outperformed a xenon-based thruster by 50 percent.

Space-based demo

Working hardware was flown on a 12-unit cubesat weighing about 20 kilograms called Beihangkongshi-1. And, over the last two years or so, the thruster has been used multiple times to handle moving the satellite to avoid potential collisions. Satellite tracking and on-board thruster monitoring show that the iodine-based thruster worked just as well as it had during testing on Earth.

It’s important to repeat that the amount of actual thrust is tiny—about 0.8 milliNewtons while in operation. But the thruster could easily maintain that for well over an hour, providing enough thrust to move it into an orbit that was a few hundred meters higher. So, while it could never put anything into orbit, ThrustMe’s hardware can definitely move things around in orbit quite well.

The big limitation again is the speed. It only moves slowly, and it takes about 10 minutes to heat the iodine enough for the thruster to start working. If an emergency maneuver was needed, this wouldn’t cut it. But, assuming nobody’s blowing up a satellite in your vicinity, most of the risks for satellites can be identified well in advance.

Nature, 2021. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-04015-y (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1813845