“NFT” picked as word of the year—deal with it

Perhaps the best thing to come from this year’s widespread adoption of the term “Non-Fungible Token” (NFT) is greater public comfort with the word “fungible.” What a perfectly cromulent word, fungible, even if it sounds like a foot powder.

Now, dictionary-maker Collins has picked NFT as its “word of the year” for 2021, mostly because people are making SRS $$$ from the blockchain-based tech. One of those people is of course the artist who goes by “Beeple”; his collection of 5,000+ everyday digital art pieces went for $69 million earlier this year, which every subsequent article on NFTs has been required to mention. This sale made Beeple one of the best-paid artists on earth. The New York Times did not love this, arguing that the gross-out and meme-based imagery of much of Beeple’s work was puerile. Also, Beeple “struggles with flesh; as in many video games, the skins appear waxy and desiccated. It’s as if every remaining human in this cryptouniverse has scurvy, though maybe that is what happens when you subordinate your flesh to the screen.” Yikes. While I agree that this was a pretty dumb way to spend $69 million, NFTs definitely have utility; for instance, just imagine how much fun it would be to buy this critic an NFT of a high-quality “OK Boomer” meme?

As for what NFTs actually are, my explanation would probably get lost in a rant about energy efficiency and the nature of originality in the digital age. Before you know it, I, too, would be banging on about “scurvy.” So I’ll let Collins try to explain things:

Collins defines [NFT] as “a unique digital certificate, registered in a blockchain, that is used to record ownership of an asset such as an artwork or a collectible.” In other words, it’s a chunk of digital data that records who a piece of digital work belongs to. “Unique” is important here — it’s a one-off, not “fungible” or replaceable by any other piece of data. And what’s really captured the public’s imagination around NFTs is the use of this technology to sell art. For example, the rights to a work by the surrealist digital artist Beeple sold at Christie’s in March for $69m. Called EVERYDAYS: THE FIRST 5000 DAYS, it was a collage of all the images he’d created since he committed in 2007 to making one every day.

See what I mean? There’s Beeple again.

NFTs can be divisive—do they liberate artists by providing new business models or are they just another money pit, the Pets.com (1998-2000, RIP) of our time? But I think we can all be thankful that “NFT” beat out “cheugy,” a word so ephemeral that I’ve already forgotten what it means.

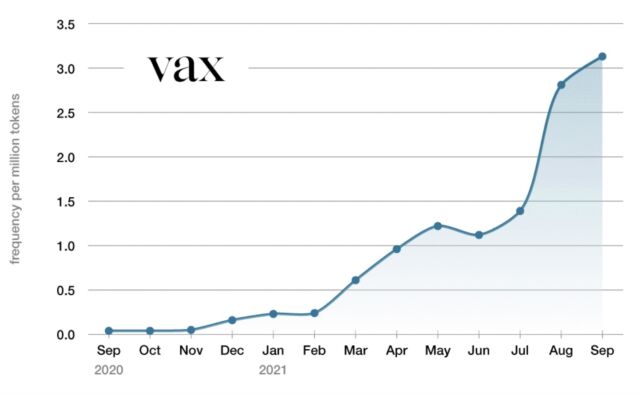

As for the slightly more staid Oxford University Press, its word of the year was “vax.” Just look at this usage chart, which resembles a graph of COVID cases in its forceful upward motion this year:

So if you don’t want to be cheugy this Thanksgiving, add “vax” and “NFT” to your word-hoards, fellow language lovers. And please join me on my quest to make 2022’s adjective of the year “post-pandemic.”

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1815601