Online schooling has a tech issue that no apps can fix

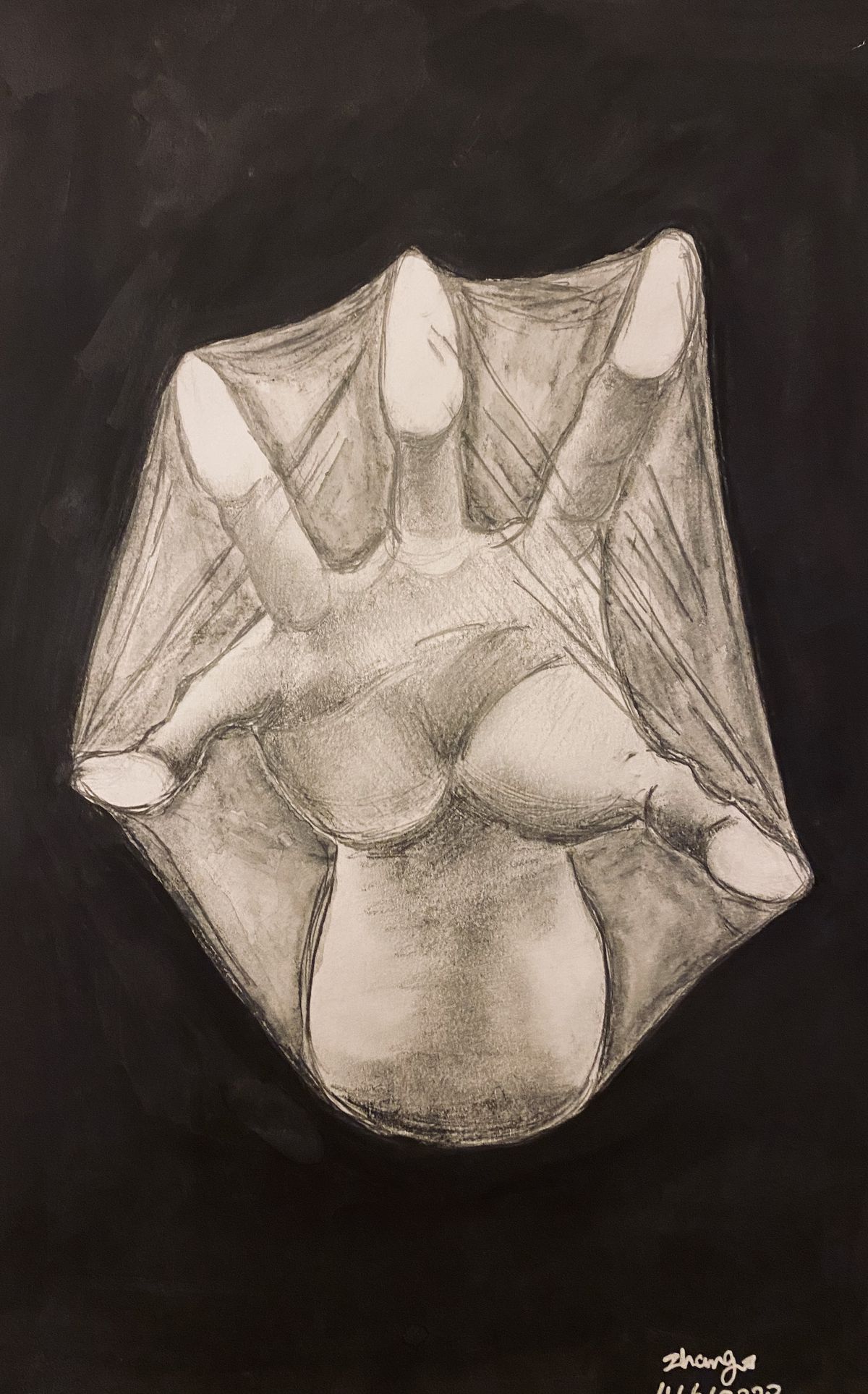

In a photo, Josh Sanders stands behind a pane of glass as he looks out onto his deck where a skateboard and bicycle have been flipped over, seemingly untouched for weeks. From his mildly furrowed expression, Josh’s longing for the outside world is painfully apparent.

The self-portrait was the seventh grade student’s response to an art class assignment to create an image capturing how he’s feeling at this moment of social distancing. The move to remote learning has forced Sanders’ teacher, Keith Sklar, to shift his curriculum from exploring traditional art mediums to creating work using whatever students can find around the house for self-expression. “The artwork that I’m getting is pretty profound — it’s much deeper content than what I’ve often seen from students in school,” Sklar tells me.

Over the past month, schools across the United States have had to quickly shift to remote learning as they adapt to social distancing measures to limit the spread of the novel coronavirus. Educators are scrambling to teach themselves software like Google Classroom, Zoom, Apple Clips, Quizlet, and iMovie to create interactive content to help students at home stay engaged, follow along, and keep coming back to their virtual classrooms.

All of the extra effort isn’t just about reimagining their lessons for the digital age, though. Despite the many tools at teachers’ disposal, many of their students aren’t able to connect due to a lack of computers, stable internet connections, or support at home to keep them focused on schoolwork. And even when they are able to log on, students still struggle in a variety of ways to follow along in their new learning environment — something teachers are finding that no amount of apps can help them resolve.

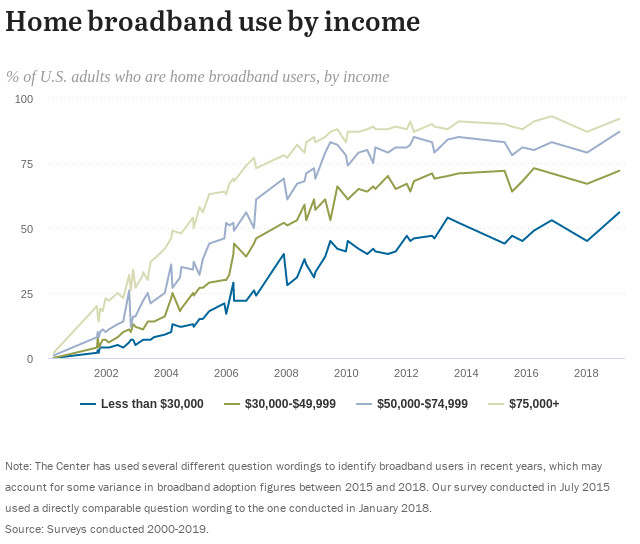

The pivot to distance learning has exacerbated equity issues among the American student body. Only 56 percent of households with incomes under $30,000 have access to broadband internet, according to Pew Research Center. Where students are located also presents connectivity issues, with kids in rural areas unable to connect to mobile hotspots and cellular service from their homes.

Even when there is stable coverage, some families simply lack the laptops, tablets, or other devices required to log online. In the days leading to citywide school closures in New York City, Brooklyn-based language arts teacher Simone Rowe said she and her peers rushed to identify students who did not have access to Wi-Fi or laptops at home. “The move to digital learning has been very hard especially with the population that I serve — over 90 percent of students need free or reduced lunch,” she says.

Though they were able to lend more than 200 laptops to students, they still struggled with making sure students could sign on and teach themselves the necessary digital classroom software to access learning materials. About 1 in 5 of the school’s 320 students hasn’t logged on. “Some students are ‘skipping,’ some can’t get on,” Rowe said. “Others have been sleeping and don’t wake up on time, some are displaced and moving around different family houses.”

Even with her school providing devices, Bay Area high school science teacher Allie Sherman says that class attendance has dropped to 60 percent since the move to distance learning. “Some households have no cellphone service so the hotspots don’t work. Many of the students are sharing devices with several siblings, including ones home from college, along with parents trying to do full time work at home on limited internet bandwidth. I know of students who’ve been driving to school and doing work in their cars using the school’s Wi-Fi,” she says.

Broadband access has been an American problem long before the pandemic, with limited competition, high prices, slow speeds, and a simple lack of coverage affecting communities nationwide. About one-quarter of Americans lack broadband internet service at home, and that gap disproportionately affects those with lower incomes and education. Access also largely affects those living in rural areas of the country where little to no broadband coverage is available, making these households less likely to have multiple devices to go online.

For Rowe, that digital divide means some students have been completely out of touch. In the past, she says her school would make house visits to students who are logged as absent for more than a week. Now, like other teachers across the country hoping to get in touch with missing students, they’re relying on phone calls and student networks to find those who’ve virtually disappeared. Classmates have helped the teachers call, text, or reach friends through social media channels to confirm whether they’ve relocated. Sometimes the efforts lead to phone numbers of guardians who kids have been temporarily placed with while their parents continue to work government-approved essential jobs. Other times, teachers find themselves with full voicemail inboxes on the other end of the line.

To assist students who do not have laptops or internet access at home, AP psychology teacher Sarah Hillenbrand in Richmond, California, says she and other colleagues convene online to put together learning materials that a volunteer later prints and packages alongside the meals that students can pick up from school. Some teachers have also found themselves helping students source laptop chargers to replace broken ones or heading to school to retrieve books students left behind before the closures.

“Digital learning has transformed us into 24/7 teachers,” Rowe says. Most teachers The Verge spoke to said they’ve given students and their parents / guardians their personal contact information, offering to be reached throughout all hours of the day. Sherman says she’s received messages in the middle of the night from students struggling to focus on education during the pandemic.

“The students just miss each other, they miss school, and they miss us. They are craving interaction,” she says. “Many are profoundly depressed, they don’t know how to manage time and work throughout the day, many are emailing me at 12 to 4AM [saying] they cannot handle the workload without the structured timing of a classroom.”

Before the pandemic, teachers were already struggling with students spending too much time on their smartphones and computer screens. But now that students are forced to rely on them for access to their education, teachers are also trying to prioritize wellness into their curriculum to ensure students aren’t spending their entire lives digitally.

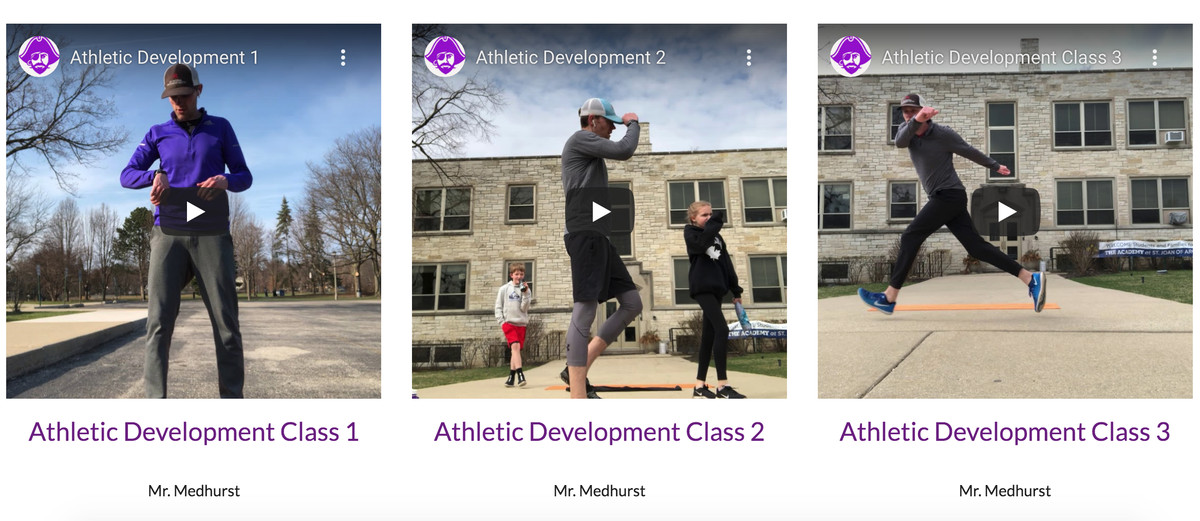

Kyle Jones, a physical education teacher who programs K–12 courses, has focused his remote lessons around personal well-being, with his peers recording videos to offer students different ways to work movements into their day. “Our approach has been more about giving resources and opportunities to move with limited to no equipment,” Jones says. His roster of content includes yoga, tai chi, martial arts, pilates, meditation, and simple footwork games kids can play with their family.

Teachers at his school have been recording themselves using GoPros, smartphones, and laptop cameras; Jones says he clips his GoPro on a fence where he films himself performing bodyweight workouts and teaching younger kids how to play hopscotch on the driveway. The teachers then edit the videos with Apple Clips and iMovie and upload them to the school’s Google Sites landing page. Some videos also feature the teachers’ own children exercising alongside them.

Tech companies have made various games and teaching tools available for free to educators, but some teachers say they feel overwhelmed with the “wall of possibilities” that comes to their inboxes every day. As part of Hillenbrand’s psychology class, she’s made personality quizzes students can take with their family members and check if the results accurately reflect them. “There’s a lot of attention-grabbing things we can do, but I think simple is better.”

While it would be easier to link out to YouTube videos and professionally designed apps, Jones says it’s more impactful for the students to see their teachers and stay engaged together through their shared limitations. “I think it’s so important the more you can make it your own and continue to allow students to see you,” he says.

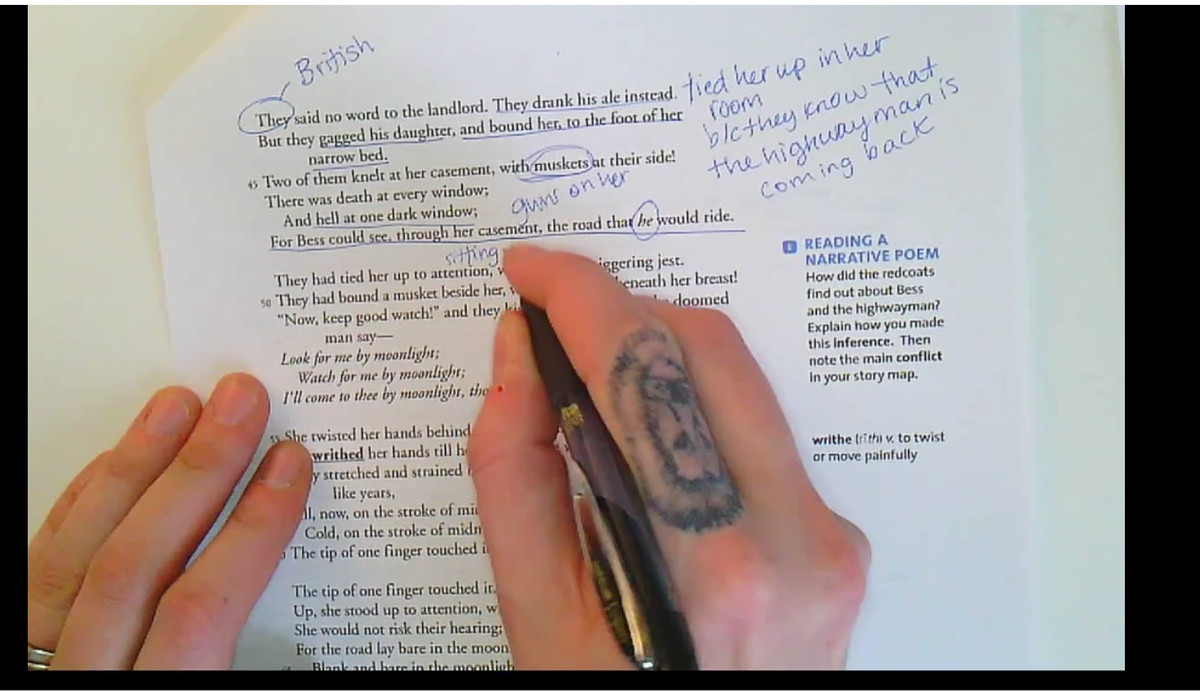

English and math teacher Kelsey Rosby has also been making herself as visible to students as she can. Rather than just assigning work and making herself available for online chats, she’s live-streamed herself annotating poetry on various platforms like Twitch and Google Meet during what would be their normal class periods. Rosby says it’s crucial that kids have the opportunity to speak with each other to discuss anything they’re feeling, whether or not they’re related to her curriculums. “I’ve been running daily emotional check-ins in a Google Chat with all my 6th graders. I do very little talking in that chat, and we usually take an hour or so to chat, to make sure everyone gets a chance to vent,” she says.

Still, Rosby feels limited as to what she’s able to do for her students’ mental health. “It feels like we are doing much, much less than what would normally happen during a day at school,” she says. Even in her attempts to reach students through platforms they are most likely to be familiar with, she knows that there will still be kids whose presence disappears entirely, whether it’s due to web access, emotional instability, or a coronavirus-related illness. “Despite my best efforts, I am so worried about each of them.”

The tech gap isn’t going to disappear anytime soon. The Department of Education and the Federal Communications Commission have begun urging states to put $16 billion in educational aid built into the CARES Act toward remote learning. But even if that happens, it’s unlikely to be anywhere close to enough. States are seeing large revenue shortfalls due to the pandemic, leading some states — like New York — to look at billions of dollars in education budget cuts alone to close the gap.

As teachers scramble to get in touch with as many students as they can, they’re also trying to find moments to celebrate small wins given the extraordinary circumstances. In Sklar’s art class, he continues to be impressed by the complexities his students bring to their digital assignments. “The strength of teaching art is you can really tap into students’ empathy and self-awareness from their own perspectives that we don’t get to see in the classroom. It’s such a profoundly awful way for something like this to happen,” he says.

Though many of the artworks have dark undertones, like an image of a student’s world on fire or a drawing of a student and their friend wearing face masks with a ruler forcing them to be six feet apart, they’ve also helped to generate valuable, thoughtful discussions among the young peers. “There’s tremendous amounts of self reflection in their work, and it’s incredible to see,” Sklar says.

While distance learning has been a struggle for both teachers and students, Rowe also says that she is not dismayed. She knows that she and teachers across the nation are working under extreme limitations, and they need to be kind and understanding to themselves if they’re going to be in this for the long haul.

“Every time a student gets something right, I get excited all over again,” Rowe says. “Sometimes a student might finish [class] and say, ‘Wow, this was fun today.’ Those are my small victories.”

https://www.theverge.com/2020/4/29/21239567/remote-school-distance-learning-digital-internet-tech-gap-devices-access