Paint drops form “fried egg” patterns if concentration, temp is just right

French scientists have been watching paint drops dry and monitoring the resulting patterns in hopes of finding ways to better control the drying process to reduce cracks and other imperfections. They found that some drops dried uniformly, while others wound up resembling fried eggs with pigmented “yolks” at the center surrounded by white, depending on pigment concentration and temperature, according to a recent paper published in the journal Langmuir.

The underlying mechanism is akin to the so-called “coffee ring effect,” when a single liquid evaporates and the solids that had been dissolved in the liquid (like coffee grounds) form a telltale ring. It happens because the evaporation occurs faster at the edge than at the center. Any remaining liquid flows outward to the edge to fill in the gaps, dragging those solids with it. Mixing in solvents (water or alcohol) reduces the effect, as long as the drops are very small. Large drops produce more uniform stains.

“Whiskey webs” are another related example. As previously reported, Princeton University physicist Howard Stone has tracked the fluid motion in whiskey drops with fluorescent markers, concluding that surfactant molecules collect at the edge of the drop. This creates a tension gradient pulling the liquid inward (known as the Marangoni effect, which is also associated with “tears of wine“). There are also plant-based polymers that stick to the glass and channel particles in the whiskey.

Stuart Williams, a mechanical engineer at the University of Louisville in Kentucky, has studied the effects of diluting a drop of bourbon and letting it evaporate under carefully controlled conditions. The result is thin strands forming various lattice-like patterns, akin to networks of blood vessels—whiskey webs. These are a hallmark of American whiskeys but do not form for their Scottish whisky counterparts. His findings showed that if the alcohol-by-volume level was above 30 percent, there would only be a uniform film; lower than 10 percent, and you get the coffee ring pattern. It’s only at an intermediate alcohol-by-volume level of between 20 percent and 25 percent that you get these unique webby structures.

Williams followed up with a second study demonstrating that the webs are different for different brands—making them a kind of “fingerprint.” The kinds of solids that are present in the whiskeys contribute to the webby pattern left behind. For instance, whiskeys aged in new charred barrels typically have more of those solids, especially those that readily dissolve in ethanol.

Similarly, when a drop of watercolor paint dries, the pigment particles of color break outward, toward the rim of the drop. So artists who work with watercolors also have to deal with the coffee ring effect if they don’t want that accumulation of pigment at the edges to happen. There have also been studies examining the mechanical properties of oil paints and other paints used by artists, with an eye toward reducing the formation of small cracks and undesirable patterns as the paint dries. Paints are complicated, containing resins, pigments, additives, and solvents such as water, and the chemical interactions between those various components during the drying process are not fully understood.

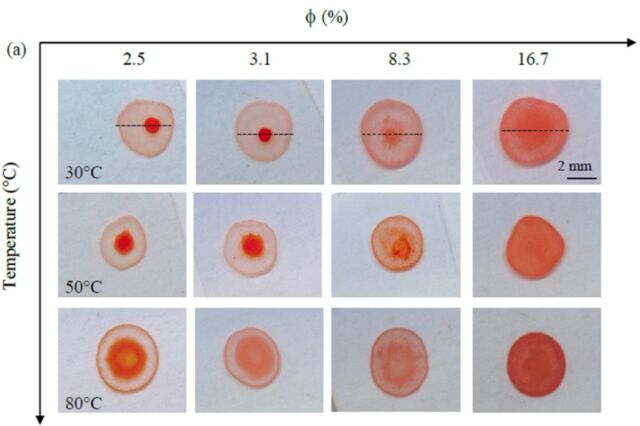

Stella Ramos and several colleagues at the Universite de Lyon in France were particularly interested in investigating the influence of two parameters on the paint drying process: the temperature of the substrate and concentration of the suspension. They used commercial water-based acrylic paint rich in resin and pigments for their experiments, diluting the samples with ultrapure water into five different concentrations. Droplets of each were deposited onto glass slides in a glass chamber with controlled temperature and humidity.

The substrates were heated to three different temperatures, and the drying process was captured from both side and top views using a CCD camera. Ramos et al. also used a scanning electron microscope to examine the surface morphology of the drops after they had dried completely; measured the surface tension; and measured the rheological properties of the paint suspensions for good measure.

The team observed three distinct mechanisms that compete with each other during the drying process. There is an initial inward flow from the heated slide to the cooler top of the drop, balanced by an outward pull from capillary action. As the droplet begins to dry, it becomes a gelatin with higher viscosity and slower movement of the pigment particles. Those particles are locked in place on the slide’s surface after the droplet fully dries.

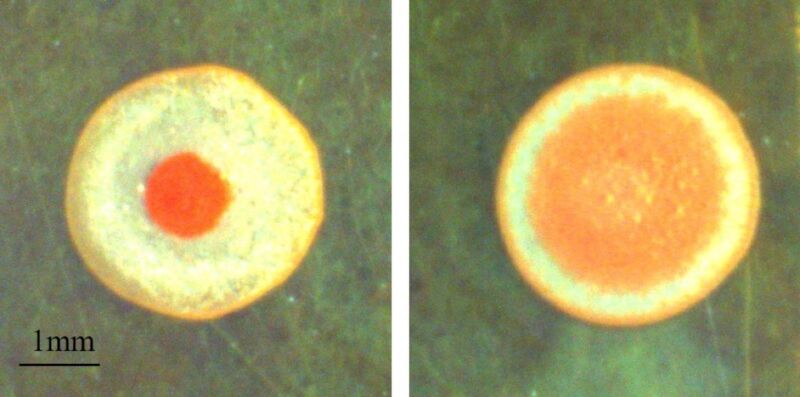

The amount of pigment and the surface temperature of the glass slide turned out to have a significant impact on the resulting size, shape, and final pattern of the dried paint drops. Specifically, paint drops with lower concentrations of pigment on slides at the lowest temperature tested (86° F) produced the fried egg pattern, while those samples with more pigment and higher temperatures (as high as 176° F) resulted in a more uniform pattern and more even distribution of color, thanks to faster gelation and drying out of the drop.

The authors concluded that one could control the appearance of dried paint by adjusting those two parameters to get the desired uniform distribution. “This experimental study deepens our understanding of the influence of substrate temperature and suspension concentration on the drying of drops made of a paint suspension, and the mechanisms governing the distribution of each pigment in the resulting deposit,” they wrote. “Better control of intricate mechanisms usually involved in the drying of multicomponent drops can thus be expected.”

Langmuir, 2023. DOI: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.3c01605 (About DOIs).

Listing image by S.M.M. Ramos et al., 2023/ACS

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1972460