Past environmental threats didn’t just disappear

Conservative political commentator Matt Walsh took to Twitter last Wednesday to say that the widely held belief that humans are causing climate change is, in fact, a crock. The podcaster and Daily Wire columnist apparently knows this because previous environmental issues we were concerned about in the past—namely acid rain and holes in the ozone layer—disappeared, never to be heard about again.

“Remember when they spent years telling us to panic over the hole in the ozone layer and then suddenly just stopped talking about it and nobody ever mentioned the ozone layer again?” Walsh tweeted. “This was also back during the time when they scared school children into believing that “acid rain” was a real and urgent threat,” Walsh tweeted again.

It’s true that you don’t hear much about acid rain anymore, and discussions about humanity’s long-standing propensity to metaphorically kick the planet in the groin have largely moved away from the ozone layer to newer, flashier issues like sea level rise, rising global temperatures, and mass species die-offs served with a side of ecosystem collapse. (Although, if you know where to look, you can still find mention of the ozone hole.)

One could, as Walsh does, take this to mean that acid rain and holes in the ozone layer simply went away on their own and were thus never anything to worry about—and that, by extension, current fears about climate change are similarly misplaced.

This would be the wrong way to take things. Ozone layer holes and acid rain have actually been dealt with in many parts of the world. In these two cases, efforts to combat environmental issues have worked. Well, mostly, at least.

Like acid rain on your wedding day

Acid rain is produced when various chemicals like sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides are emitted into the atmosphere, usually by the burning of fossil fuels, emissions from vehicles, and manufacturing and other industries. The airborne compounds mix with water and fall to the ground as low-pH rain, harming various species and corroding metals and other materials humans use for buildings.

In many areas around the world, especially those in which coal was used to generate electricity, acid rain caused serious problems. In the US and other areas, it’s no longer an issue only because various governments around the world took action.

The US Congress updated and strengthened emission regulations in 1990 and, by 2003, the amount of sulfur dioxide raining down had decreased—by 40 percent in the northeastern US, for instance. Between 1990 and 2019, the US saw a 93 percent reduction in sulfur dioxide emissions. Similar regulations also popped up in Europe, and international agreements were negotiated in an effort to curb the issue. In 2002, The Economist called the fight against acid rain “the greatest green success story of the past decade.” Acid rain is still an issue, just not as much of one.

The hole story

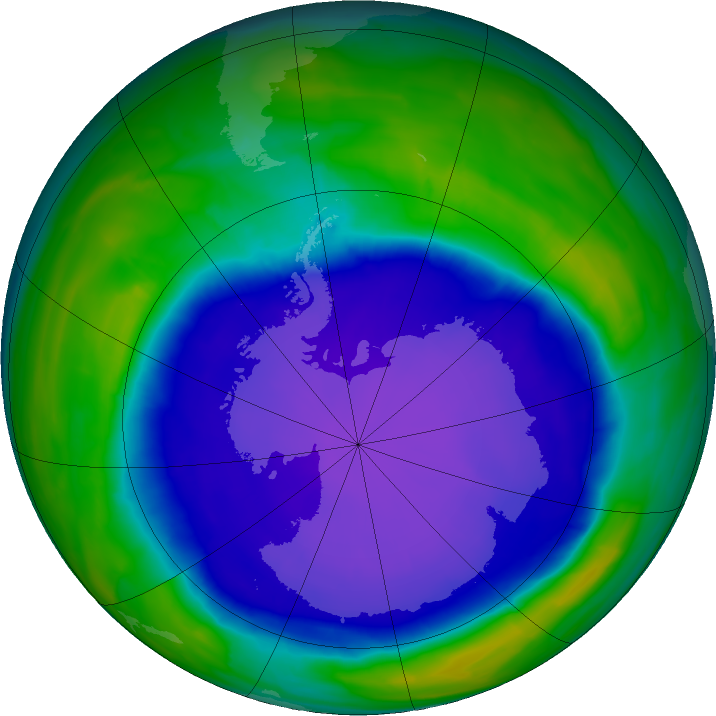

Back in the 1980s, scientists discovered, much to their dismay, that human activity was depleting the ozone layer. And it wasn’t thinning evenly; there was even a hole—more accurately, an extreme thinning—in the ozone layer over Antarctica. The hole was traced back to certain gases—ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs)—that were widely used in the 1980s, particularly in fridges, air conditioners, and similar pieces of equipment.

The ozone layer helps protect the Earth by absorbing radiation at certain wavelengths, and the hole allows more UV radiation from the Sun in. This, in turn, boosts the levels of UV damage living things experience, increasing rates of skin cancer and possibly leading to a general increase in mutation rates.

Much like acid rain, the hole in the ozone layer caused governments to take action. In 1987, nations around the world adopted the Montreal Protocol to protect the ozone layer through the phasing out of the chemicals that damage it. This included a staggered phase-out schedule for some countries and the creation of a multilateral fund to provide some countries money and technical support.

Again, much like acid rain, the problem hasn’t totally gone away. In 2021, the Antarctic ozone layer hole grew to its 13th largest size on record since 1979. But overall, the trends are good.

What’s the deal?

It’s tempting to think that these weren’t really problems but rather mistakes on the part of the scientific community or that, even if they were a big deal back in the day, they’re not problems anymore. Neither is true, however. Acid rain, ozone layer depletion, climate change, and biodiversity loss are all very real problems. The former two are less of an issue than they might be, thanks to some successful mitigation efforts.

Walsh’s tweets are willfully ignoring some very well-documented history, and they disregard truly massive bodies of scientific literature. Granted, it’s hard to get historic context in a tweet or two, but that doesn’t excuse this sort of blatant error.

Unfortunately, Walsh has around 1 million followers on Twitter, and the tweets garnered more than 41,000 likes. So, while his tweets may have just been quick throwaway comments, they’re likely to have a significant effect on many people’s perceptions.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1868623