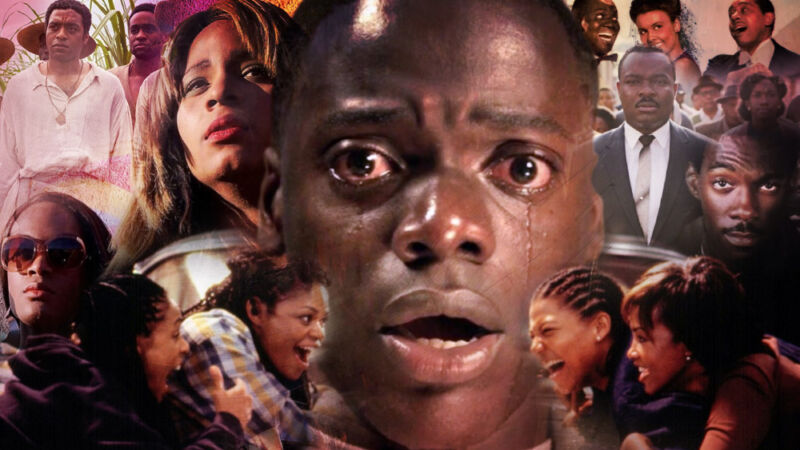

Skip The Help. Celebrate Juneteenth by watching a few of these 25 films.

Today we are celebrating Juneteenth—the day in 1865 when Union Army General Gordon Granger read federal orders in Galveston, Texas, declaring that all slaves in the United States were now free. And what better way for the Ars Technica culture desk to mark the occasion than by offering a sampling of 25 films from the last 100 years, produced by, directed by, written, and/or starring leading black professionals in the entertainment industry?

This is by no means intended to be an exhaustive overview or a definitive list. I’ve just picked a few films to highlight from different time periods, spanning several different genres: everything from early “race films,” jazz musicals, and blaxploitation, to buddy-cop action, ensemble comedies, superhero films, historical dramas, quirky indie films, gritty urban dramas, and so forth.

There are far more titles from 2000 on. That’s partly because so much of film history has been effectively “whitewashed;” partly because the studio system that dominated the so-called Golden Age of Hollywood put a chokehold on diversity for decades; and partly because there are now so many more such films to choose from. More than ever, black producers, directors, writers, and actors are finding the means to tell their own stories—and finding a receptive, enthusiastic audience for those stories.

Laying these films out chronologically conveys a sense of how broad cultural shifts get reflected in the medium. It also makes abundantly clear what black filmmakers have been saying for ages: representation matters, at all levels of production, but particularly at the top, because that’s where it’s decided which films ultimately get made—and who gets to make them. (Similarly, the dearth of black representation in Oscar nominations and wins reflects the longstanding lack of diversity among the members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.) There has been a great deal of progress. But as recent comments to the Los Angeles Times, from nearly two dozen black professionals in the entertainment industry, should make abundantly clear, we still have a long way to go.

(Some spoilers below.)

Within Our Gates (1920)

This is the oldest-known surviving film from the “race films” era and the second of more than 40 such films directed by Oscar Micheaux. Within Our Gates tells the story of a young black woman named Sylvia (Evelyn Preer) who travels north to raise money to build a school for rural black children in the Deep South. She finds love with a handsome doctor named V. Vivian (Charles D. Lucas) and eventually learns she is of mixed race; her father was the wealthy white landlord who had financed her education.

Film historians generally view Within Our Gates as a blistering response to D.W. Griffith’s pro-Ku Klux Klan silent film The Birth of a Nation (1915), given its frank depiction of attempted rape and lynchings. In fact, the film had trouble gaining approval by Chicago’s Board of Censors, largely because the city feared reigniting the Chicago Race Riot of 1919. Other cities also either blocked screenings or demanded certain scenes be cut. The controversy actually boosted interest in the film, which attracted fairly large audiences in Chicago.

Within Our Gates was presumed lost until the 1970s, when a single print was found in Spain with Spanish intertitles and a short middle sequence missing. The Library of Congress restored the film as close to the original as possible in 1993, including English intertitles and a frame summarizing what had happened in the missing sequence. You can watch the entire film online, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Stormy Weather (1943)

Bill “Bojangles” Robinson starred in this classic Hollywood musical based on his own experiences trying to break into show business after serving in World War I. Stormy Weather was a rare musical that featured a largely black cast, in an era when lead roles generally went to white actors and actresses. Some of the top musicians of that era are featured, including Lena Horne—who plays aspiring singer Selina Rogers and performs the title tune—Fats Waller (performing “Ain’t Misbehavin'”), and Cab Calloway, among others. The fabulous dancing duo the Nicholas Brothers also appear, along with Katherine Dunham and her dance troupe. Fred Astaire declared the dance sequence performed to Calloway’s “Jumpin’ Jive”—in which the Nicholas Brothers descend a staircase by leaping over each other into full splits, among other jaw-dropping moves—the “greatest movie musical number” he’d ever seen.

Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967)

Sidney Poitier was arguably the first mainstream black movie star, winning a Best Actor Oscar for Lilies of the Field (1963) for his portrayal of a handyman who helps a group of nuns build a chapel. He was only the second black actor to be so honored, following Hattie McDaniel‘s Best Supporting Actress win for playing Mammy in Gone With the Wind (1939). While he certainly played his share of “stereotypical” roles in Hollywood, he is best known for evincing a suave, sophisticated Cary Grant vibe, and nowhere is that more apparent than in his seminal portrayal of Dr. John Prentice in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.

Young Joanna Drayton (Katharine Houghton) returns from a vacation and presents her white liberal parents—newspaper publisher Matt Drayton (Spencer Tracy) and his wife, art gallery owner Christina (Katharine Hepburn)—with her new fiancé, Poitier’s John Prentice. John’s parents fly in for dinner as well, and both sets of parents struggle mightily with their children entering into an interracial marriage, given the degree of prejudice against such unions. The entire film is just a series of conversations, as the characters offer arguments and counterarguments, moderated by family friend Monsignor Mike Ryan (Cecil Kellaway). One highlight: John telling his father that while the father thinks of himself “as a colored man… I think of myself as a man.”

The film ultimately came down strongly on the side of interracial marriage (love is love) and was thus a harbinger of major changes to come. Just days after Tracy shot his final scene, the US Supreme Court handed down its unanimous decision in Loving v. Virginia striking down any state laws banning interracial marriage. Alas, Tracy was very ill during the entire shoot and died 17 days after it ended. Hepburn was so heartbroken she could never bring herself to watch the final film.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1684379