German man got 217 COVID shots over 29 months—here’s how it went

A 62-year-old man in Germany decided to get 217 COVID-19 vaccinations over the course of 29 months —for “private reasons.” But, somewhat surprisingly, he doesn’t seem to have suffered any ill effects from the excessive immunization, particularly weaker immune responses, according to a newly published case study in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

The case is just one person, of course, so the findings can’t be extrapolated to the general population. But, they conflict with a widely held concern among researchers that such overexposure to vaccination could lead to weaker immune responses. Some experts have raised this concern in discussions over how frequently people should get COVID-19 booster doses.

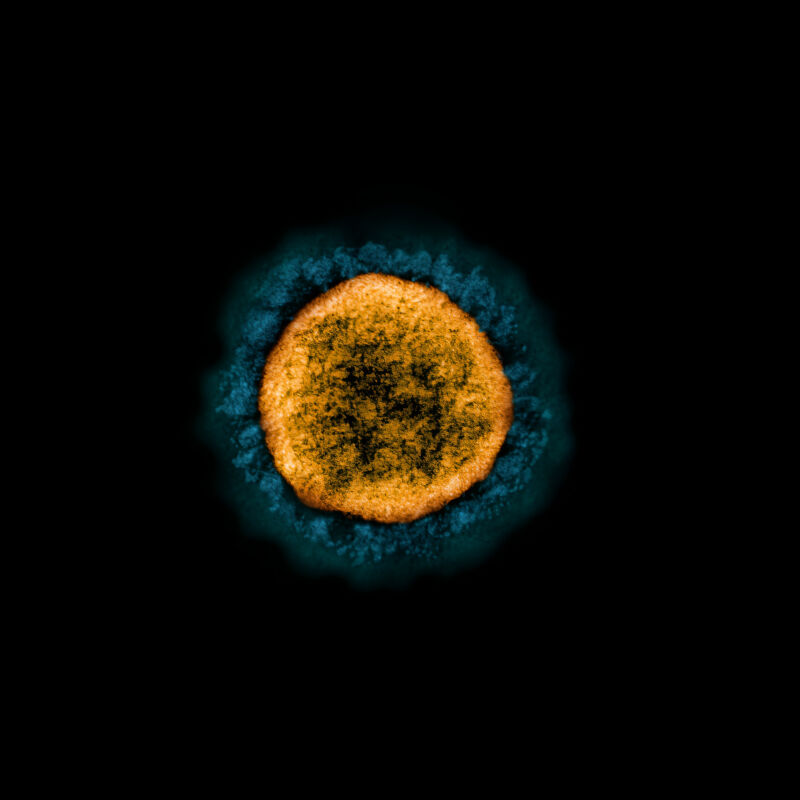

In cases of chronic exposure to a disease-causing germ, “there is an indication that certain types of immune cells, known as T-cells, then become fatigued, leading to them releasing fewer pro-inflammatory messenger substances,” according to co-lead study author Kilian Schober from the Institute of Microbiology – Clinical Microbiology, Immunology and Hygiene. This, along with other effects, can lead to “immune tolerance” that leads to weaker responses that are less effective at fighting off a pathogen, Schober explained in a news release.

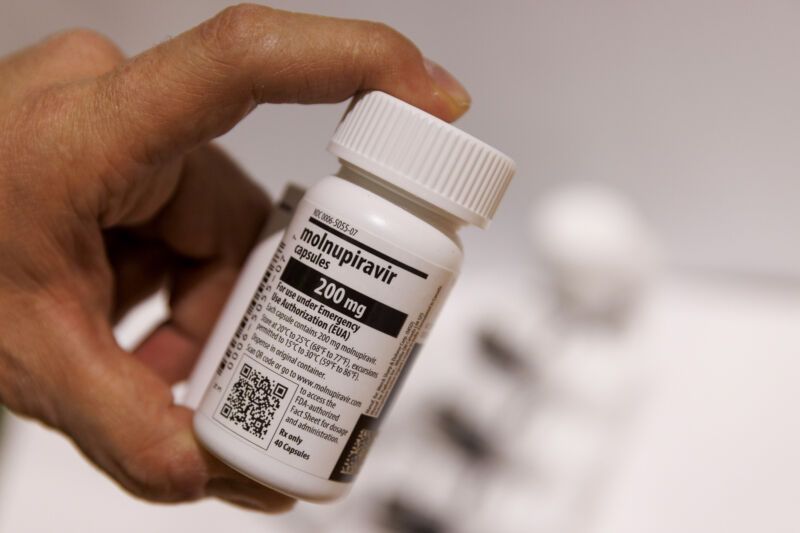

The German man’s extreme history of hypervaccination seemed like a good case to look for evidence of such tolerance and weaker responses. Schober and his colleagues learned of the man’s case through news headlines—officials had opened a fraud investigation against the man, confirming 130 vaccinations over nine months, but no criminal charges were ever filed. “We then contacted him and invited him to undergo various tests in Erlangen [a city in Bavaria],” Schober said. “He was very interested in doing so.” The man then reported an additional 87 vaccinations to the researchers, which in total included eight different vaccine formulations, including updated boosters.

The researchers were able to collect blood and saliva samples from the man during his 214th to 217th vaccine doses. They compared his immune responses to those of 29 people who had received a standard three-dose series.

Throughout the dizzying number of vaccines, the man never reported any vaccine side effects, and his clinical testing revealed no abnormalities related to hypervaccination. The researchers conducted a detailed look at his responses to the vaccines, finding that while some aspects of his protection were stronger, on the whole, his immune responses were functionally similar to those from people who had far fewer doses. Vaccine-spurred antibody levels in his blood rose after a new dose but then began declining, similar to what was seen in the controls.

His antibodies’ ability to neutralize SARS-CoV-2 appeared to be between fivefold and 11-fold higher than in controls, but the researchers noted that this was due to a higher quantity of antibodies, not more potent antibodies. Specific subsets of immune cells, namely B-cells trained against SARS-CoV-2’s spike protein and T effector cells, were elevated compared with controls. But they seemed to function normally. As another type of control, the researchers also looked at the man’s immune response to an unrelated virus, Epstein-Barr, which causes mononucleosis. They found that the unbridled immunizations did not negatively impact responses to that virus, suggesting there were no ill effects on immune responses generally.

Last, multiple types of testing indicated that the man has never been infected with SARS-CoV-2. But the researchers were cautious to note that this may be due to other precautions the man took beyond getting 217 vaccines.

“In summary, our case report shows that SARS-CoV-2 hypervaccination did not lead to adverse events and increased the quantity of spike-specific antibodies and T cells without having a strong positive or negative effect on the intrinsic quality of adaptive immune responses,” the authors concluded. “Importantly,” they added, “we do not endorse hypervaccination as a strategy to enhance adaptive immunity.”

https://arstechnica.com/?p=2008036