Focus can make or break an image. And unlike other elements necessary for a successful photo, either the focus is perfect, or it’s not. You might get away with a slightly sloppy exposure; or your framing may not be 100% as you wished; even the lighting or timing can be less than perfect, and yet, all in all, it may still make for a stunning shot.

But if the focus is out, that’s it. There’s nothing to be done but hit the delete button.

Accurate and appropriate use of focus is one of the most basic – and yet most important – techniques you must master as a beginner photographer. There is nothing more frustrating than having produced an otherwise great photo, only to discover that the focus is slightly “soft” when the file is viewed at 100% magnification on a computer screen.

There are so many things that can go wrong when shooting a photo that you can’t control yourself – the sun, for example, or a subject’s behavior – that you’ll want to at least be fully on top of those elements which you can control. While even the pros produce a few out of focus shots from time to time, you can bet that the majority of their photos are tack sharp, without even thinking about it. That’s what you should be aiming for too.

However, focus is much more than merely a minimum requirement for producing a technically acceptable photo. Deliberate and considered use of focus is also one of the most important creative tools in your photographic arsenal, helping you to lead your viewer towards what – for you – are the most important elements of the image, and away from those that you’d rather they didn’t concentrate on. How you use focus can also radically alter the mood of a photo, shifting the atmosphere from clinical clarity to atmospheric visual poetry.

But to make full use of these techniques, you must first gain a solid understanding of how focus works, which is precisely the purpose of this guide.

What Do We Mean By Focus in Photography?

First, though, it would be beneficial to define exactly what we mean when we talk about focus in the context of photography.

Shine a light on a wall and place your hand between the wall and the light source, at a distance of a couple of feet from the wall. You should see a recognizable shadow of your hand on the wall. Notice, though, that the edges of the shadow are not sharply defined, but are instead a little soft and diffused. But move your hand closer to the wall, and the shadow becomes sharper, its form less fuzzy. Now place your hand just a fraction of an inch from the wall, and the shadow will become very sharply focused.

If instead, you move your hand in the opposite direction, much closer to the light, the shape of the shadow will become less and less defined until it may not be recognizable as a hand at all. The shadow is now totally out of focus.

Although you may not be conscious of it, in order to read this article, your eyes have focused on the screen of your device. Keep them looking here, entirely concentrated on the text, but see what else your eyes can take in around your device – whether in the background or foreground. Probably you can recognize other objects in the environment around you, out of the “corner of your eye.” But notice that anything either in front of or behind your device appears somewhat fuzzy and unclear compared to the text on the screen.

Now move your eyes to one of those objects in the background or foreground and try to get a better look at it, allowing your focus to shift from the screen to the object.

We lost you for a second, right? And in order to continue reading this, you will have had to move your eyes back to the screen to make the text sharp and legible again. If you tried to read the screen while keeping your eyes on the background, you will likely have gone cross-eyed, ending up with a double image of the screen.

A camera lens works in the same way. At the most basic level, not everything in front of a camera can be in focus at the same time in a single photo. Or rather it can, but you’ll need to know how camera focus works in order to be able to achieve this. That’s what we’ll be looking at in the first part of this article.

But then there’s the question of whether you will even want to make the entire image sharply focused, or instead carefully control which parts of the image are focused and which are not, for creative effect. We’ll get to that a little later on, towards the end of the article.

Camera Focus: Technical Considerations

How the Camera Focus Works

Your camera has a lens. This lens is used to capture rays of light from outside in such a way that they precisely converge on the camera’s image sensor, creating a sharp image. The sensor itself likely has a great many focus points which can be used to tell the lens to focus on a specific object within a scene – i.e., at a specific distance from the camera. Now not only the object we’ve focused on, but all other objects positioned at the same distance from the camera, will be sharp. This arc of sharpness, including all parts of the image that are in focus, is called the focal plane.

Decades ago, cameras could only be focused manually, by turning a ring on the lens barrel until the optical elements inside the lens were positioned in such a way as to provide sharp focus at the desired distance. Today many DSLRs, Mirrorless, and other types of cameras still offer the possibility to focus manually in this way. Of these, some are truly manual, just like with an old film camera (i.e., adjusting the focus ring will directly and mechanically move the lens elements). Meanwhile, others are effectively a simulated version of manual focus. Such systems are often called “focus by wire.” Here touching the focus ring does not mechanically move anything in the lens directly, but instead sends information to the camera body; which in turn tells the motors which control the lens elements to move, electronically.

While manual focus operation certainly has its uses (particularly in macro photography, for complicated rack focusing in video, or when focusing in very low light), from the late ‘80s onwards nearly all cameras have come with some form of autofocus capability. Since then, autofocus technology has improved considerably, and there are now a primary couple of methods in which cameras achieve focus automatically.

Phase Detection Autofocus

Employed by all DSLRs. Also used by some Mirrorless cameras.

Phase Detection autofocus splits light entering a camera lens into two identical images, which are then phase-corrected (i.e., realigned) by the camera in order to determine correct focus distance. As this process initially required a mirror in order to split the light beams, it is most commonly found in DSLRs. However, despite lacking a reflex mirror, more recent models of Mirrorless camera sometimes also employ this method, by incorporating the beam splitter into the image sensor.

Phase Detection autofocus provides detailed information about the distance of the subject from the camera and is therefore well-suited to focus-tracking fast-moving subjects, where continuous rapid adjustments of focus in small increments are typically required.

Contrast-Based Autofocus

Employed by nearly all Compact cameras, many Mirrorless cameras, and by all DSLRs when used in Live View mode.

When a scene is out of focus, one object will seem to blend into the next, without any clearly defined forms, contours, or details. Conversely, when an object or a part of a scene is in focus, there will be a maximum degree of contrast between all its finer details and contours. Contrast-based autofocus uses this knowledge to determine when an area of a scene is in focus: depress the focus button of your camera and the focus sensor will adjust the position of the lens elements until maximum intensity of contrast is achieved in the selected area of the frame – thus assuring that this part of the image is sharp. However, as this method of focusing does not produce any information regarding the distance between camera and subject, it is less suited to the tracking of moving subjects.

These two methods of focusing work in entirely different ways: the first measures distance, providing the camera with an understanding of the relative positioning of elements within the frame; the second merely adjusts the lens elements until maximum contrast is achieved, but cannot differentiate between objects positioned on separate focal planes.

In practice, both systems have their advantages and disadvantages, and therefore, it is common for modern cameras to employ both methods. Sometimes these methods work together simultaneously: for example Phase Detection may be used to set focus to an approximately correct distance, at which point Contrast-Based autofocus kicks in, fine-tuning focus for greater accuracy.

At other times the different methods are used separately and for different purposes. This is notably the case with DSLRs, which use the Phase Detection system as their primary method of focusing, but must switch to using Contrast-Based AF when operating in Live View mode, due to the fact that the reflex mirror – upon which the use of Phase Detection AF depends – is no longer accessible.

When assessing a scene, the human brain looks for a variety of “clues” – both visual and otherwise – that help it to understand three-dimensional space and the distance between objects. Despite being equipped with a highly sophisticated computer, a camera is not capable of understanding all these signs regarding spatial information but instead relies upon the detection of small, contrasty details within the scene in order to understand which parts of the frame contain objects. This means that autofocus often struggles in situations where the subject lacks contrast (for example, a textureless wall, or a cloudless sky) or where there is insufficient light available to differentiate between one detail and the next.

Autofocus Area Modes

Whereas early models of autofocus cameras often featured just a handful of autofocus points – or perhaps even just a single one in the center of the frame – modern cameras often feature many more autofocus points distributed across their sensors, providing much greater accuracy. These focus points can be used in a variety of different ways, depending on the shooting situation.

Single Point AF

In Single Point autofocus mode only one of the camera’s autofocus points is active. Pressing the focus button will cause the lens to focus on this exact point within the frame. The user can decide precisely which point is active through the camera’s menu.

Dynamic Area AF

As with Single Point AF mode, in Dynamic Area mode, just a single autofocus point is selected. However, other nearby focus points will also be active, allowing the camera to make adjustments to focus should the subject move slightly within the frame. The user can decide the precise range of autofocus points in use through the camera’s menu.

Auto Area AF

In Auto Area AF mode, the camera makes all decisions regarding focus for the user. While this may seem like an appealingly convenient option, in practice the camera is as likely to get things wrong as to get them right, often leading to the focus being set on an entirely incorrect area of the frame.

Types of Focus Point

Different camera models use different types of focus point. “Normal” focus points can detect only vertical lines and are the most commonly available type of focus point. Increasingly though we see cameras using a large number of Normal focus points, augmented by a range of more sophisticated “Cross-Type” focus points in certain areas – particular towards the center of the frame. Cross-Type AF points are capable of detecting both horizontal and vertical lines and therefore provide greater accuracy than Normal points.

Frequently camera manufacturers will not only state the number of focus points a particular model of camera offers, but also, of these, how many are the more desirable Cross-Type points.

Camera Focus Modes

Typically a camera will offer different focus operation settings, either by means of a physical switch on the camera body or the lens itself or by way of the camera’s LCD menu.

Manual Focus

Focus must be set by manually turning a ring on the lens barrel.

Single Shot AF

Depress the shutter button halfway, and the camera will set focus. Once focus is set, this position will be held until the shutter is fired, at which point the shutter button must be half depressed again in order to reset focus.

Continuous AF

As with Single Shot AF, depressing the shutter button halfway will set focus. However, the camera will continue to adjust focus if either the camera or the subject moves before a picture is taken. This makes Continuous AF ideal for tracking fast moving subjects.

Back Button Focus

Normally, when you purchase a new camera, its standard factory settings will place focus control on the shutter release button: half depress the shutter and AF will spring into action. On many camera models, however, this is a feature that can be customized, with the user able to assign AF control to another button of their choice – typically a custom function button on the rear of the camera whereby AF is set using the thumb rather than forefinger.

Many photographers prefer this set-up, as it keeps focus entirely independent from the shutter release. Meaning that focus can be set, and will stay in place even when repeatedly shooting, without the risk of the focus position changing each time the shutter is fired.

Focus Range Limiter

Some lenses come with a Focus Limiter function, typically selectable by means of a button on the lens barrel itself. This feature allows the user to restrict focusing to a predetermined (and often fully customizable) distance range.

The advantage of this is that, if you know that your subject (even a moving subject) will remain at an approximate distance from the camera, you can tell the lens only to look for points to focus upon within this distance range. This way, there is much less risk of “focus searching” wherein autofocus jumps backward and forwards between foreground and background objects looking for a point to focus on.

Lens Calibration

Although you might expect a manufacturer to ship your new camera fully set up for optimal focusing performance right out of the box, many photographers and manufacturers alike recommend calibrating DSLR bodies to their lenses for improved accuracy. Indeed, you will frequently come across terrifying articles online telling you that you must do this; otherwise, your photos will all turn out terrible.

However, as alarming as this may sound, the majority of professional photographers go through their entire careers without ever having calibrated a lens. Lens calibration will, of course, be beneficial, but for those photographers less concerned with “pixel peeping” every technical deficiency, and more interested in just producing good photos, obsessing over such details might not be worth the bother (however, see the troubleshooting section below for an example of when you may need to calibrate).

Camera Focus in Practice

Having gained an understanding of how a camera sets focus, we now turn our attention to to how focus works in practice.

Visual Depth

A photograph is a two-dimensional object, yet always represents three-dimensional space. This being the case, we need to have some understanding of how those three-dimensions behave when reduced to just two.

When we refer to the depth of a scene, we are referring to the visual clues that tell us about the size and shape of objects and the distance between them in three-dimensional space. A sheet of paper has almost no depth when viewed front-on: hold it out in front of you vertically, or lay it on a table and look at it from directly above, and its entire surface will be more or less on the same plane; i.e., the same distance from you.

But lay the paper horizontally on your hands and lift it almost to the same height as your eyes, and one edge of the paper will be much closer to you than the other. Consequently, its surface will no longer all be on the same plane in relation to you, but will instead recede into the distance.

Behind the paper, there will likely be other objects in your field of view, and perhaps a wall beyond them. Maybe there’s even a window in the wall, providing a view of the outdoors? In which case, the scene has much greater visual depth than if you were merely looking at a sheet of paper laying flat on a table.

Continue to hold the sheet of paper horizontally on the palm of your hand with its surface receding into the distance, but hold it as far away from you as possible now. You will likely be able to visually take in the entire sheet of paper from front to back. And – providing that the typeface isn’t too small – if there’s anything written on the paper you will probably be able to read it without having to move your eyes too much.

Now move the paper so that its closest edge is almost touching your nose. If you’ve got good eyesight, you’ll probably have no problem moving your eyes so that the edge furthest away from you is sharply focused.

But what about the nearest edge? Can you focus on it? And can you focus on both the nearest and the furthest edge at the same time? The background too?

Cameras also struggle with this.

Depth of Field

The degree to which a camera can capture all the elements of a scene in focus, from foreground to background, is called depth of field. If the distance between the closest and furthest objects in an image that is acceptably sharp is relatively small (i.e., only a narrow portion of the image is in focus), this is called a shallow depth of field. Conversely, if there is a considerable distance between the closest and furthest elements of an image that are sharp (i.e., both objects close to the camera and those much further away are sharply focused), this is called deep depth of field.

Several different factors influence the depth of field of any given photo. Indeed depth of field is a complicated topic that deserves a separate guide all of its own. Nonetheless, we’ll need to acquire at least a basic understanding of depth of field if we are to make effective use of focus in our photography.

As you probably already know, changing the lens aperture (f/stop numbers, such as f/2.8, f/11, etc.) opens or closes the lens diaphragm, letting in either more or less light. But because changing the size of the hole through which light enters your camera also changes the angle at which light enters, changing the lens aperture affects depth of field too.

A wide aperture (i.e., a low f/stop number such as f/1.8 or f/2) causes light to enter the lens at a steep angle, contributing to a shallow depth of field. Meanwhile, a small aperture (e.g., a high number such as f/16 or f/22) forces the light to enter the lens and hit the camera’s image sensor at a more horizontal angle, leading to a deeper depth of field.

Although opening or closing the lens diaphragm always affects the depth of field, it is unfortunately not the only determinant of the depth of field. Indeed, our ability to control depth of field is made more complicated due to the fact that a number of other considerations also influence it. These include:

Lens focal length

A wide-angle lens (such as a 24mm or 28mm) will produce a fairly deep depth of field at nearly all aperture settings; while a telephoto (e.g., a 200mm or 300mm) lens will always produce a much narrower depth of field than the wide-angle lens, even when the two are used at identical aperture settings.

The relative distance of the camera to subject vs. subject to background

Simply put, if you focus on a subject that is closer to the camera than the background, the background will be out of focus. But focus on a subject that is closer to the background than the camera, then both subject and background are likely to be fairly sharp.

The sensor size of your camera also influences depth of field: the bigger the sensor, the shallower the depth of field that can be achieved using that particular camera. But as this is not something that we as photographers can control (beyond choosing to use a particular camera rather than another) we will not go into this matter in any greater detail here. Just bear in mind that if you feel that you have understood everything we’ve covered so far in this guide, and yet you are still struggling to achieve a very shallow depth of field in your photographs, the most likely explanation is that you are using a camera with a “cropped” (i.e., not full frame 35mm) image sensor.

To recap then, depth of field refers to the degree to which objects in front of and behind the main point of focus are also sharp. So, for example, if I focus my camera on a house but both the hill behind the house and a tree in front of it are also relatively sharp, we would say that this is a deep depth of field. If, on the contrary, only the house is sharply focused, but both the hill and tree are blurred, we would refer to this as a shallow depth of field.

It is important to note that the distance in which objects that fall to the front of the plane of focus will still be sharp is smaller than the distance for which those located behind the plane of focus will be sharp. The distance from the nearest acceptably sharp object to the central point of focus makes up just a third of the depth of field. Meanwhile, the distance from the point of focus to the furthest acceptably sharp object makes up the remaining two-thirds of the depth of field. The importance of this observation will become clear in just a second.

Hyperfocal Distance

When shooting a landscape photograph, we generally want as deep a depth of field possible, so that ideally all elements in the frame are acceptably sharp from background to foreground.

Let’s say that we are photographing mountains. We usually want the focal plane (the point of maximum sharpness) to be on the subject. Here the subject of our photo is the mountain range, which is so far away that in order to correctly focus for them we would need to set the lens to infinity (i.e., the furthest point at which the lens can focus). Is that what we should do?

Actually, no.

Remember that one-third of the depth of field extends in front of the point of focus, while two-thirds extend behind it. This means that if we set focus on the mountains – at infinity – we will only benefit from one-third of the depth of field potentially available to us: i.e., the portion in front of the mountains. This is because the other two-thirds of our depth of field will be beyond the mountains. But it’s only possible to focus up until infinity anyway, so all that depth of field beyond the mountains is going to waste where it makes no difference to the sharpness of any element visible in our photo.

In short, you should never focus at infinity unless you specifically want a single object at infinity to be in focus at the expense of all other elements within the frame. Instead, in most cases, you’ll want to focus at the hyperfocal distance for the scene you are photographing.

Hyperfocal distance refers to the point furthest forward within a given scene on which you can focus and still get everything beyond that point acceptably sharp all the way to infinity – while of course also benefiting from the remaining third of the depth of field-stretching forwards from the focus point towards the camera.

As hyperfocal distance depends on a great many variables (distance, lens, aperture, etc.), precisely calculating hyperlocal distance involves some pretty complicated math, so it’s much simpler just to use a dedicated app to do the job for you. In a pinch though, you can probably get away with guessing it, by using a very small aperture and shifting your point of focus somewhat forwards of infinity.

Focus vs. Depth of Field vs. Sharpness

Up until now, we’ve put a lot of emphasis on the concept of depth of field in relation to focus. However, it is important to understand that the terms focus, depth of field, and sharpness do not refer to the same thing.

• Sharpness refers to the degree to which elements within an image are clearly defined, showing maximum detail and with a strong contrast between their edges. How sharp a given photo is depends on various factors, including the quality of the lens, the size and resolution of the camera’s image sensor, the aperture used, etc.

• The point of focus (or focal plane) is where the optical elements within the camera lens have been set to provide maximum sharpness of all objects positioned at a given distance from the camera. Objects either in front of or behind the point of focus will become less sharp when moving away from the point of focus.

• The degree to which sharpness decreases when moving away from the point of focus is referred to as depth of field. As already mentioned, whether the depth of field is deep or shallow depends on a variety of interrelated factors.

The reason that we need to be clear about these three different points is because we are about to introduce a further concept that will likely seem counterintuitive after all that we’ve said so far about maximum depth of field being achieved at the smallest aperture settings (f/16, f/22). Before we throw this spanner into the works though, let’s be clear: if f/22 is the smallest aperture that your lens offers, this will indeed produce the deepest depth of field achievable with that lens. However, what we also need to understand is that shooting at f/22 may not produce the sharpest photo possible with that lens.

What does this mean? Well, remember that depth of field specifically refers to the degree to which objects in front of and behind the point of focus are also in focus. So at f/22, most objects in the frame, all the way from foreground to background will likely be relatively in focus. But this doesn’t necessarily mean that they will be sharp – sharpness referring not to the depth of field, nor how well the camera has been focused, but to the optical rendering and resolution of the image.

Sharpness is independent of both focus and depth of field, and in terms of image sharpness, most lenses perform at their best when used at medium apertures – i.e., not at either their maximum or minimum apertures. Although every lens is different, typically a lens will produce the sharpest results approximately somewhere between f/5.6 and f/16.

This means that sometimes you will need to make a decision as to which is more important: deep depth of field, or maximum image sharpness.

For example, if all I care about is achieving a very deep depth of field, so that the whole image is in focus, and I don’t mind losing a tiny bit of resolution, then shooting at f/22 will be the best option.

However, perhaps I plan on making a very large print of the photo. In which case, I might decide that it’s more important to achieve maximum sharpness. As long as I don’t mind compromising slightly on the depth of field in order to get it, then I might get better results shooting at f/16 or even f/13.

Creative Use of Focus in Photography

Up until now, we’ve primarily spoken about ways to achieve a “correctly focused” image by the application of technical knowledge. However, as with so many things in photography (and indeed other art forms), “correct” is a somewhat subjective term. There are certainly many recommended ways of approaching focus that are widely considered appropriate to different types of photography. But this isn’t to say that you must follow these recommendations every single time. Sometimes a photo can be successful precisely because it plays with the viewer, confounding their expectations.

Nonetheless, for the most part, there are good reasons why certain types of photographs are commonly shot in a particular way. You should certainly be aware of how other photographers approach the kind of images you are interested in shooting, but then it’s up to you to decide what works best for the exact image you want to produce; for the exact message you wish to convey, or atmosphere you want to evoke with your photography. Creative use of focus can play a big part in this.

Where to Focus?

When approaching a shot, any shot, your first questions should always be “what’s the subject here?” All your creative and technical decisions – from focus to angle, framing, and exposure – hinge on the answer to this single question.

Sometimes identifying the subject of a photo can be more difficult than it sounds. Especially when it’s the kind of wide view where it was more the general overall impression of the scene that first caught your eye, rather than any single detail in particular. For example, a busy street or a landscape scene.

Even in such cases, there will always be one element of the scene that is key to the success of the whole image. If in doubt, just ask yourself what is the first element of the scene that you want your viewers to notice when they look at the photo. This is likely the subject. Ninety-nine times out of a hundred, you’ll want to focus here.

Occasionally though – especially when using a narrow depth of field – you may want the viewer to have to work a little harder to understand what’s happening in the image. So don’t entirely rule out the possibility of focusing elsewhere, drawing the viewer’s attention to a secondary (but important) object in the frame, and then leaving them to make sense of what’s happening in out of focus areas; which may, in fact, contain the real subject of the photograph.

As already mentioned, there are certain tried and tested approaches to focus in photography that generally produce the best results. If you are creative, rules are certainly there to be broken. But you’ll need to fully understand those rules, and the reasons why they have achieved that status, before you can think about deviating from them.

There now follow some suggestion as to how you might best approach two of the most common photographic genres in terms of focus. If interpreted fairly liberally, these two genres cover most photographic scenarios you are ever likely to encounter.

Landscape Photography

Landscape photography is probably the genre of photography which most values a deep depth of field. The reason for this is straightforward: if you have a wide landscape scene, one particular element (a mountain, a tree, a rock) may provide the central point of interest and will probably be where you should focus, but it’s also quite likely that the rest of the landscape is of almost equal importance. If you use a shallow depth of field to draw attention to just one feature of the landscape, leaving the rest of the scene without sharp definition, viewers will likely find this quite disturbing, as there is nowhere else for the eyes to settle on as they scan across the rest of the image.

This problem becomes even more acute when a landscape photo is printed up as a big enlargement (for an exhibition, for example). Why produce such an enormous view of the landscape if so little of the image contains useful (i.e., sharp, recognizable) visual information? If instead, the image is fantastically sharp from front to back, the viewer will be free to explore every minute detail with great pleasure.

Although other genres of photography such as interiors and architecture differ from landscape photography on a number of other points, when it comes to the matter of focus, much of the advice commonly given for landscape photography holds equally true. There are certainly many cases in which a shallow depth of field may work very well in either an architectural or an interior shot, but these will inevitably be for photos of the more artistic kind. But for more practical uses, a deep depth of field and setting focus on a pivotal element of the scene will produce the best results the majority of the time.

Portrait Photography

Portrait photography lies at the other end of the extreme to landscapes. Here a shallow depth of field is usually more desirable. The reason here is that, in contrast to a landscape which is often more about providing a general view of a scene, a portrait has a very clear subject that makes all other elements within the frame pale into insignificance. That subject is, by definition, of course, a person (or an animal).

The subject of a portrait is even more narrowly prescribed than this: while a portrait is always about a person, when we view a person we generally look at their eyes. And in almost every single case, this is where you’ll need to focus, or risk severely frustrating the viewer.

But what happens when you’re photographing more than one person in a single shot? Here, you will still need to focus on somebody’s eyes. The question is, whose eyes?

If it’s obvious that one of the people you are photographing is more important for one reason or another, then clearly it should be this person whose eyes are sharply focused. But if you have two or more individuals who are all of equal importance, you face a choice of either focusing on the person nearest to the camera, lining everyone up on the same focal plane, or shooting at a smaller aperture setting for a deeper depth of field.

Other Photography Styles

With other genres of photography such as reportage, street photography, still life, travel, etc. whether you opt for a landscape or portrait kind of approach to focus will largely depend upon the precise nature of the image you wish to create; the intended final use or audience; and the precise atmosphere you want to achieve.

Focus is a subtle way of manipulating your viewers, drawing their attention to the information you want them to see, in the order you want them to see it. For this reason, it is one of the most valuable tools in a visual storyteller’s kit bag, and consequently, your approach to focusing should never be taken for granted.

Nonetheless, any photo you might conceivably want to shoot will fall somewhere between the two main approaches characterized above.

Why Aren’t My Photos Sharp?

Are you problems with focus? Use this checklist to identify the cause.

Problem: The photo is sharp, just not where you want it to be.

Likely causes:

• Either you or the subject may have moved after you set the focus. This can often happen when setting focus, using focus lock, and then recomposing the shot before firing the shutter. If you’re shooting with a wide aperture, depth of field may be so shallow that even altering your position an inch or two when reframing can result in an out of focus subject.

• If focus control is assigned to the shutter release button, you may have accidentally refocused before firing the shutter.

• If your lens has a Focus Limiter function button, check that this is in the off position. It may be blocking your lens from focusing at the correct distance for your subject.

• If you are shooting a portrait at a very narrow depth of field, check that the subject is fully facing the camera front-on: if their head is turned half in profile, one eye will be further away from the camera than the other, potentially resulting in one eye being sharp while the other is blurred. Generally, you will want to focus on the eye closest to the camera; the only exception being if this eye is in deep shadow, in which case it may be better to focus on the eye that is further away.

• If static parts of the image are sharp while moving elements are blurred, this is not a problem of focus, but instead caused by shooting at an inappropriately slow shutter speed.

• Your lens may need calibrating.

Problem: No part of the photo is sharply focused.

Likely causes:

• Again, check that the Focus Limiter function is off, as this could be stopping your lens from focusing at the correct distance for the subject.

• This may not be a focus problem at all, but could instead be caused by movement or vibration of the camera while making the exposure. If you are hand-holding your camera, check that you are using a sufficiently fast shutter speed. Use a tripod if necessary. Even if using a tripod, strong wind or other vibrations may cause photos to become blurred.

• Alternatively, if the image seems soft, grainy or pixelated, the problem may have nothing to do with focus but instead be a simple case of poor image quality, This could either be caused by severely underexposing the photo, using too high an ISO, or may just be because of a small, low-resolution image sensor.

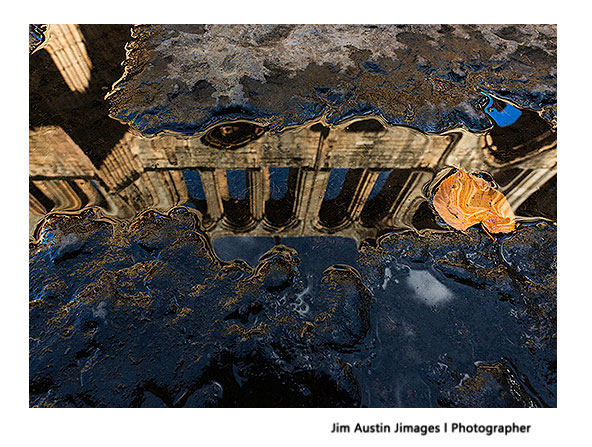

Understanding Focus in Photography

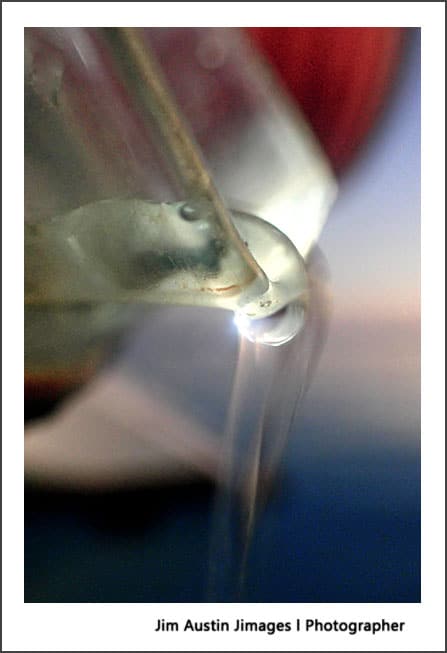

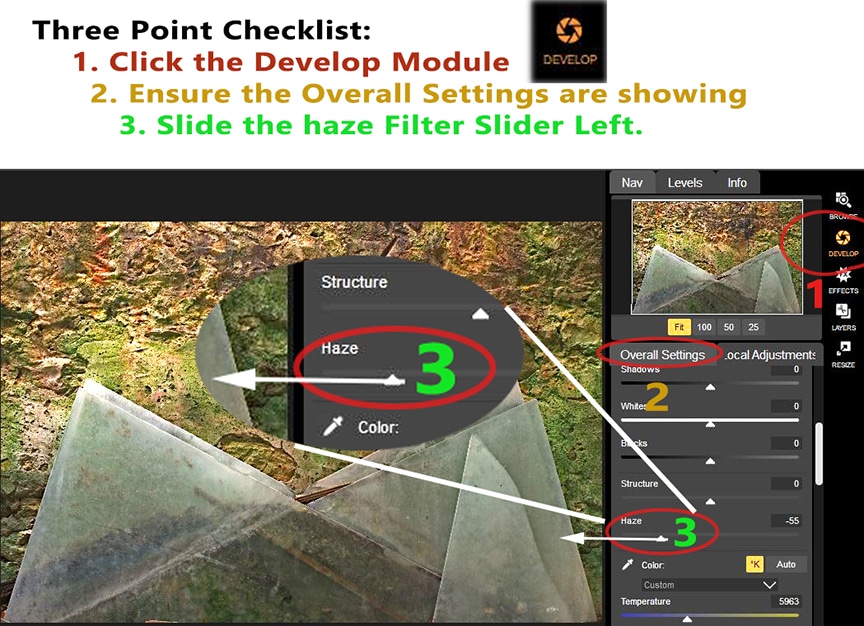

Above, a scene of a lighthouse window shows the Haze filter (-minus) improving color saturation outside a window without overly saturating the interior. Below, the HAZE slider (-) was applied to a RAW image of broken lighthouse tower glass leaning against a rough dark wall.

Above, a scene of a lighthouse window shows the Haze filter (-minus) improving color saturation outside a window without overly saturating the interior. Below, the HAZE slider (-) was applied to a RAW image of broken lighthouse tower glass leaning against a rough dark wall.