The (fossil) eyes have it: Evidence that an ancient owl hunted in daylight

An extraordinarily well-preserved fossil owl was described in PNAS this past March. Owls are not new to the fossil record; evidence of their existence has been found in scattered limbs and fragments from the Pleistocene to the Paleocene (approximately 11,700 years to 65 million years ago). What makes this fossil unique is not only the rare preservation of its near-complete articulated skeleton but that it provides the first evidence of diurnal behavior millions of years earlier than previously thought.

In other words, this ancient owl didn’t stalk its prey under the cloak of darkness. Instead, the bird was active under the rays of the Miocene sun.

Seeing the light

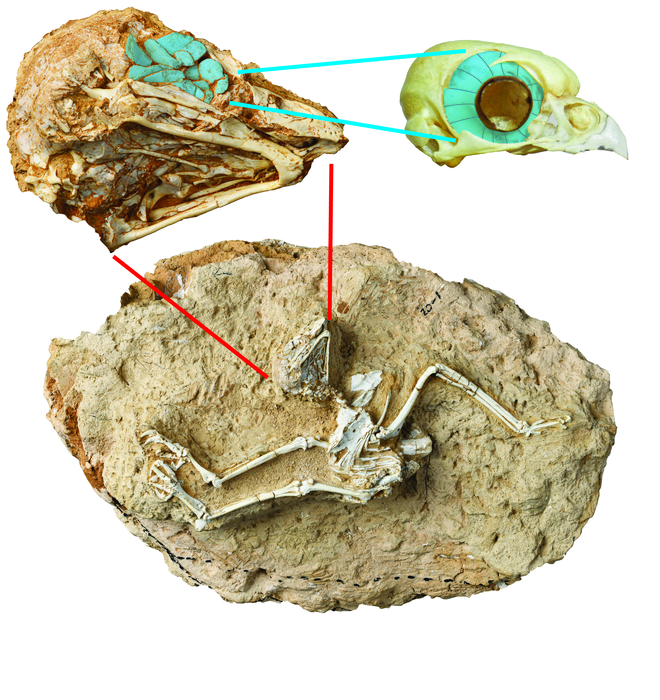

Its eye socket was key to making this determination. Dr. Zhiheng Li is the lead author on the paper and a vertebrate paleontologist who focuses on fossil birds at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) in China. He explained in an email that the large bones around the eyes of birds (but not mammals) known as the scleral ossicles offer information about the size of the pupil they surround. In this case, the pupils of this fossil owl were small. And if the pupil is small, he wrote, it “means they can obtain good vision with a smaller eye opening.”

Co-author Dr. Thomas Stidham is an integrative biologist and avian paleontologist at the IVPP. He described the scleral ossicles as “roughly trapezoidal in outline (with the narrow part toward the center of the pupil).” They “overlap each other to make a ring with a smaller internal circular opening and a larger circumference on the outside of the ring. The internal opening emcompasses the iris and pupil,” he said.

“Nocturnal birds,” he continued, “need a larger opening to let in more light than what is needed for eyes used during the day (where a smaller opening/pupil will let in enough light to see). We did statistical tests on the scleral ossicle rings of hundreds of species of birds and lizards that are active at night, dusk, and daytime.”

How and when owls evolved their day/night preference is exceedingly difficult to ascertain, as the owl fossil record in deep time is fragmentary. And one of the biggest clues to whether an owl is active at day or night lies within the skull, the fossils of which can be elusive.

A fragmentary history

Thus, having a well-preserved skull offers rare insight into at least one species during the Miocene. The researchers’ analyses put this fossil owl within the Surniini clade (“clade” is a term that refers to a group with a common ancestor), which includes diurnal owls today, such as pygmy owls and the northern hawk owl. If this ancient owl was diurnal millions of years ago, it’s likely that its subsequent close relatives were as well.

“From a parsimonious view of evolutionary history,” Li clarified, “the explanation with the fewest evolutionary changes is the most likely.”

He and his colleagues named this new mid-sized species Miosurnia diurna, a name that nods to its existence within the Miocene period, its resemblance to today’s northern hawk owl (Surnia ulula), and its diurnal behavior.

According to Li, the fossil was found some time ago by a farmer in Hezheng county and donated to the Shandong Tianyu Museum, where it remained among “thousands of feathered dinosaurs and a large number of much older birds fossils” until it caught the attention of Li and his team. Found within the Linshiu Formation in Tibet, it is approximately 6 million to 9.5 million years old.

This exquisite specimen is almost complete, missing only one forelimb and a few digits. Its preservation is so extraordinary that it even has stomach contents: small bone fragments of what the team thinks are equally small mammals based on bone residues. Li wrote that he and his team feel that, although it’s still within the body, this stomach content is actually a gastric pellet “since the position of the residue is more likely in the upper part of [the] digestive tract.” He added that the “shape of the bone residue was quite pellet-like.”

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1856327