The Game Awards has made its peace with what it can and can’t do

It’s been two years, and Geoff Keighley, creator of The Game Awards, is still thinking about the Schick Hydrobot.

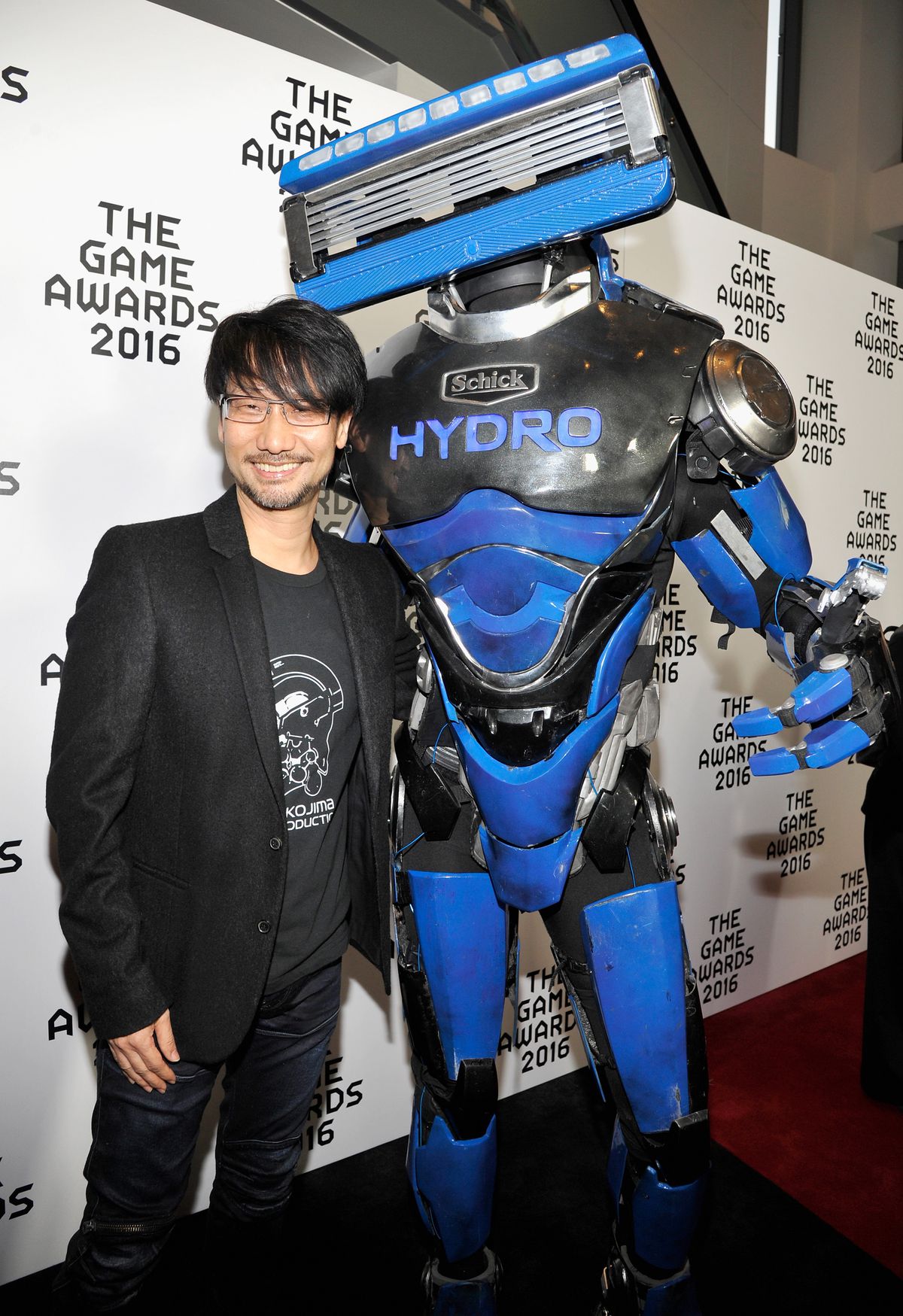

In 2016, while the glitzy industry celebration was enjoying its third show, viewers were preoccupied with the night’s strangest guest: a marketing gimmick in the form of a shockingly buff blue-and-silver robot with a nightmarish razor blade for a head. It walked the red carpet. It posed with games luminary Hideo Kojima. And, much to the chagrin of many viewers, its silent, hulking form appeared in segments throughout the night.

Marketing integration isn’t a sexy concept, and not even broad shoulders and biceps can make it so. Online, people gleefully ridiculed lines like “Hydrobot, taking it to the next level!” and “Hydrobot, at it again!” Fake Hydrobot accounts cropped up almost immediately. Viewers and attendees alike decried it as corny, a strange and off-putting brand insertion that had nothing to do with games.

Hydrobot was an instant meme, but also a metaphor for the event itself. Part award show, part hype train, The Game Awards combines highlighting the people who make games with the bombastic “world premiere” announcements fans have come to expect from annual events like E3. But much like the still young industry itself, the show has a history of straddling the line between earnest and awkward. For every profound moment, like honoring the long and impactful career of Atari designer Carol Shaw, there is an equal and opposite reaction — like developer Josef Fares’ long and swear-filled “fuck the Oscars” rant that would never fly on any other stage. And certainly no one, not even Keighley, has forgotten Hydrobot, an appearance Rolling Stone called “the deformed child of a loveless commercial union,” while Forbes dubbed it one of the show’s most cringeworthy moments. Keighley references Hydrobot often in interviews, usually as a lesson learned. (Schick’s presence the following year was more tasteful, instead opting to sponsor the Best Debut Indie Game.)

Now in its fifth year, TGA isn’t just the biggest show in games. It’s a mirror image of the industry itself, flaws and all. “We’re here to celebrate games and the people in the industry, both who make games and also those who play them,” Keighley tells The Verge. His vision has always been to bring the gaming community together to celebrate a medium that doesn’t always get the respect he thinks it’s due.

The Game Awards are often held up as the Oscars of the game industry, despite Keighley’s repeated insistence otherwise. “The show is very different, right?” he says. “We focus a lot on forward-looking content world premieres … [they] are our celebrities, right? We certainly have celebrity talent in the show, but [the event] doesn’t sink or swim based on that.”

Part of that shorthand may have to do with Keighley’s history. He’s long been invested in — maybe even obsessed with — elevating games as a medium. The kid of two Academy Awards members, he reflects on what the Oscars meant to his parents, and how desperately he wished for games to have an equivalent. It’s a deep-rooted desire going back to his childhood, when he got involved in writing script lines for Cybermania ‘94, the first-ever games award show, at age 14. There never was a Cybermania ‘95, but he’s enjoyed a long and successful career as a print journalist and host, notably the now-defunct Spike Video Game Awards. After it folded, Keighley invested a staggering $1 million of his own savings to get his own show off the ground in 2014. “It felt like none of those [previous award] shows had really delivered on [their] mission,” he says. “In many ways, they were compromised because they were on traditional television networks and were going after this mythical mainstream viewer.”

With the rise of live-streaming platforms like Twitch and YouTube, Keighley saw a huge opportunity to create a show on his terms. “That’s what really birthed the show, this belief that no one else was going to do what I wanted to do,” he says. “There was a window of opportunity to create something, and I better seize it.” It’s worked out in his favor. Where the first live stream in 2014 pulled in 1.9 million viewers, numbers in its fourth year soared to 11.5 million. Each show is a nearly year-round project, from booking the venue to visiting publishers and working with developers to hash out what will appear onstage. “We’re kind of over that hump now in terms of people believe in the show, support it, continues to grow in terms of audience,” Keighley says.

This year, The Game Awards found comfortable footing. It’s been, as Keighley says, refined: Three hours of game industry figures and occasional celebrities slipping in to hand off awards and give short speeches; orchestral music of beloved songs; trailers announcing new titles — though many of the night’s surprises leaked online before the show aired. New to the show this year was a joint effort between the awards and Facebook Gaming to showcase an increasingly global presence, and short segments aired between game announcements while crowd members checked their phones. In these moments, extraordinary individuals like accessibility nonprofit AbleGamers’ COO Steven Spohn were allowed to shine and share their stories.

That’s not to say The Game Awards hasn’t gone out of its way to showcase members of the community before. In fact, it’s led the way in highlighting the community with its long-running Trending Gamer award. “Games are participatory type of entertainment, and the player is a part of the story because these are naturally interactive,” Keighley says. When the first awards show kicked off, it was clear that platforms like Twitch were instrumental in the community.

But creators in the games space have a slippery habit of getting into trouble. The very first Trending Gamer, the late TotalBiscuit, has a sticky legacy because of his involvement with Gamergate. Last year’s winner, Dr DisRespect, has been known to mock Chinese accents on stream. Even current industry darling Ninja, award presenter and the winner of this year’s Content Creator of the Year (a replacement for Trending Gamer), has used racial expletives on-stream and sparked controversy for refusing to stream with women. Keighley is aware of the responsibility that comes with highlighting creators with problematic attitudes and the delicate balance of community impact vs. morality. Nominating a game means nominating a product. Awarding a person suggests endorsement of their beliefs and personality.

Asked before this year’s show, Keighley says show organizers do think about who gets the spotlight. “We want who’s involved in the awards to hopefully reflect the community in a positive light, right?” he says. “And if you’re a gamer and passionate about this medium, you’ve been for many years marginalized, I think, in the perception of who is a gamer. So when someone is going to get up there and be involved in the show, you naturally want that person to represent the best of the industry.”

Part of that meant moving away from the idea of virality, since “people sometimes trend for the wrong reasons” and into the idea of Content Creator of the Year. This placed the focus instead on what people were creating. “[There’s] the larger question about who has the right to be nominated, who has the right to win in these categories,” he says. “Our description of Content Creator of the Year is to recognize someone who’s had a positive impact on the community.” Judges are asked to keep this in mind while voting, as it’s ultimately that input that decides. “But beyond that, it’s really hard, and I certainly don’t want to be someone who’s disqualifying someone because they had a personal issue, etc., etc.”

Under this friendlier, safe umbrella, Ninja’s would-be win was obvious. No one can deny that he’s drawn attention and respect to the community on a mainstream level. He’s been, for the most part, a well-meaning and likable ambassador for games as a medium. At the Awards, Ninja was also a presenter, onstage with a punny prawn muppet. But instead of going for a weak bit, would it have been more powerful for him to present alongside, say, a human woman?

Keighley admits that, for now, the show’s featured content creators are still largely Western-based. As the show pivots to tackle the next stage of its life, the goal is to take it global — in the people it features, and in a literal sense. “Longer term I would love this show to travel every year and make it a destination,” he says. He pitches a hypothetical future where the end of each show reveals next year’s location — somewhere in Shanghai, or Tokyo, in a way no other award show can match. “I think we can because we’re not so celebrity dependent,” he says. A focus on streaming, rather than aspiring to be on TV, doesn’t hurt either. “I’ve learned what this audience wants,” he says.

There’s an endearing optimism to The Game Awards in its best moments — moments where a newly crowned winner like Dominique “SonicFox” McLean can happily declare himself “gay, black, a furry” and still be the ESports Player of the Year. But in 2018, the audience, it seems, also wants to see games like Red Dead Redemption 2 sweep the awards without even a wink to the questionable labor practices that made them. They want to see industry celebrities who have had their questionable choices unquestionably forgiven. An awards show may not be the place to dump the industry’s dirty laundry onstage. But the process itself to get to those awards, and of how we talk about winners — who deserves that love without an asterisk — is worth interrogating.

“Maybe one day we’ll have more viewers than the Oscars, and that’ll be a watershed moment for the entire industry,” Keighley says. “But we’re not there yet.”

https://www.theverge.com/2018/12/7/18131058/game-awards-2018-geoff-keighly-creaotr-streaming-tga-hydrobot