The NES: How it began, worked, and saved an industry

In honor of Uemmura’s career and his lasting impact on the game industry, we’re republishing this 2013 piece we ran on the Famicom’s 30th birthday, diving deep into the technical details of the system and exploring its history and legacy.

We’re right on the cusp of another generation of game consoles, and whether you’re an Xbox One fanperson or a PlayStation 4 zealot, you probably know what’s coming if you’ve been through a few of these cycles. The systems will launch in time for the holidays, each will have one or two decent launch titles, there will be perhaps a year or two when the new console and the old console coexist on store shelves, and then the “next generation” becomes the current generation—until we do it all again a few years from now. For gamers born in or after the 1980s, this cycle has remained familiar even as old console makers have bowed out (Sega, Atari) and new ones have taken their place (Sony, Microsoft).

It wasn’t always this way.

The system that began this cycle, resuscitating the American video game industry and setting up the third-party game publisher system as we know it, was the original Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), launched in Japan on July 15, 1983, as the Family Computer (or Famicom). Today, in celebration of the original Famicom’s 30th birthday, we’ll be taking a look back at what the console accomplished, how it worked, and how people are (through means both legal and illegal) keeping its games alive today.

From Japanese beginnings to American triumphs

The Famicom wasn’t Nintendo’s first home console—that honor goes to the Japan-only “Color TV Game” consoles, which were inexpensive units designed to play a few different variations of a single, built-in game. It was, however, Nintendo’s first console to use interchangeable game cartridges.

The original Japanese Famicom looked like some sort of hovercar with controllers stuck to it. The top-loading system used a 60-pin connector to accept its 3-inch high, 5.3-inch wide cartridges and originally had two hardwired controllers that could be stored in cradles on the side of the device (unlike the NES’ removable controllers, these were permanently wired to the Famicom).

The second controller had an integrated microphone in place of its start and select buttons. A 15-pin port meant for hardware add-ons was integrated into the front of the system—we’ll talk more about the accessories that used this port in a bit. After an initial hardware recall related to a faulty circuit on the motherboard, the console became quite successful in Japan based on the strength of arcade ports like Donkey Kong Jr. and original titles like Super Mario Bros.

The North American version of the console was beset by several false starts, to say nothing of unfavorable marketing conditions. A distribution agreement with then-giant Atari fell through at the last minute after Atari executives saw a version of Nintendo’s Donkey Kong running on Coleco’s Adam computer at the 1983 Consumer Electronics Show (CES). By the time Atari was ready to negotiate again, the 1983 video game crash had crippled the American market, killing what would have been the “Nintendo Enhanced Video System” before it had a chance to live.

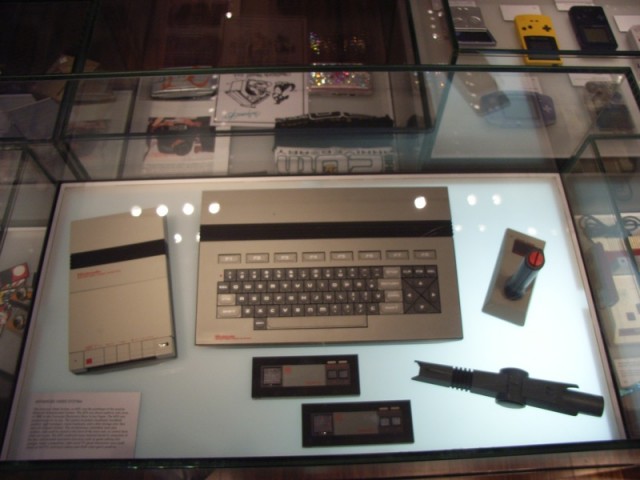

Nintendo decided to go its own way. By the time 1985’s CES rolled around, the company was ready to show a prototype of what had become the Nintendo Advanced Video System (AVS). This system was impressive in its ambition and came with accessories including controllers, a light gun, and a cassette drive that were all meant to interface with the console wirelessly, via infrared. The still-terrible market for video games made such a complex (and, likely, expensive) system a tough sell, though, and after a lukewarm reception, Nintendo went back to the drawing board to work on what would become the Nintendo Entertainment System we still know and love today.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=305397