War Stories: How This War of Mine manipulates your emotions

Chances are good that you already have This War of Mine in your Steam library. The side-view, survival-horror adventure game is a perennial favorite on various Steam sales, and at least 4.5 million people have picked up a copy since its release in 2014. But as with many Steam sale titles, it’s perhaps a bit less likely that you’ve played the game—and if you haven’t, that’s a shame, because it’s damn good.

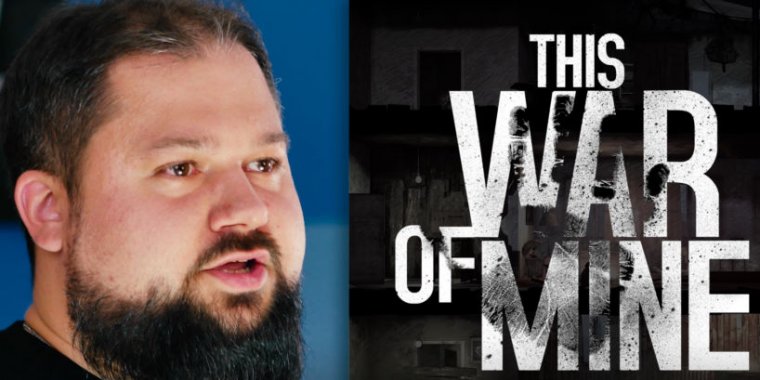

But it’s also a hard game to experience—and I’m not talking about the difficulty level. This War of Mine’s developers are Polish, and they come from a country and a culture that still bears the scars of post-war Nazi occupation. Lead programmer Aleksander Kauch explained that one of the primary things developer 11 Bit Studios wanted to do with TWoM was to bring the stories of his grandparents to life—to put players into a place where joy and normalcy have been replaced by starvation and bleakness, where there are no good choices, and where the biggest and best thing you have to hope for is that you might scavenge enough supplies to live a few more days.

War is hell

It wasn’t an easy journey. Kauch explained that TWoM drew a lot of initial inspiration from Lucas Pope’s masterful Papers, Please—a game that managed to cram a tremendous amount of story into what is effectively “Paper Stamping Simulator Pro.” With TWoM, Kauch wanted to build an environment where you managed a group of survivors living among the post-war ruins, but as the prototype came together, it became obvious that what they were making wasn’t quite hitting the right mark.

Kauch described the prototype as “War Sims,” and it just wasn’t fun enough. The prototype had players juggling stats and trading and fortifying things, but there was no emotional connection to your people. So the game’s developers changed things up a bit—if the game felt impersonal, it was time to make it personal. With extreme prejudice.

L’audace, l’audace, toujours l’audace!

The implementation of the solution was done boldly. Rather than fleshing out the player character with a grand backstory to give the player some identity to latch onto, the developers decided to make the player more and more uncomfortable in their surroundings—to emotionally manipulate the player by forcing them into making uncomfortable choices in situations where all possible outcomes are negative. This was done, explains Kauch, by setting up “an emotional trap” for the players. One of the potential locations the game offers for players to explore is a safe-looking home inhabited by a harmless old couple. The old couple has medicine and some supplies, and they are completely defenseless.

Anything the player does with them is effectively wrong. If the player chooses to leave them in peace, the player loses the opportunity to take their supplies and the player’s own group suffers. Conversely, if the player steals their medicines and supplies, the old couple begs and cries for the player for mercy, saying they will die without them (which they eventually do). There is no “good” way to resolve the solution, and all outcomes are designed to leave the player questioning their own actions.

Further, Kauch and his team added a “depression level” to the game’s characters, in order to further amplify the consequences of the player’s choices. As things become more terrible, characters in the player’s group will begin to develop emotional problems and will not perform as well. If things become too terrible, characters can abandon the group and run away—or even commit suicide.

The illusion of control

The developers also realized that they could also make the game’s characters more real by manipulating players’ sense of agency. “Michat Drozdowski, our creative director, made an observation on that when the player faces something that he does not understand that seems random to him, he feels that he loses control,” explained Kauch. “And the feeling of lost control is an essential part of the game because the player loses control, he starts to pay attention to every single detail that can help him. He’s trying to get a hint from basically anywhere.”

The intent was that the players would search the environment and interface both for hints and would therein discover things like the details in their squad’s character bios. Those bios may mention traits like “good at math” that seasoned adventure game players might think important—after all, why show a detail if it’s not important?—but little of what players discover will be of help with the game. The primary purpose of it all is to force players into more of a bond with their little band of survivors. The game is designed to pull you in, to force you to make difficult choices, and to live with them—assuming you live.

Choices, choices everywhere

This War of Mine is a game defined by its cultural roots—it is a Slavic game, created by people from Central Europe who grew up hearing stories of Nazi occupation from their grandparents. It lacks most of the hallmarks of more stereotypically “Western” stories—there isn’t a happy ending or even a particularly neat resolution. It is not a game designed to give you a quick dopamine hit of joy or to tell a complex tale of good and evil. Instead, it is a game designed to make you feel something—to evoke emotions and then to force the player to confront and contemplate those emotions.

It would likely have been somewhat successful purely as a War Sims resource management-type game, but by tangling up the player’s feelings and expectations, it becomes so much more. Kauch puts it best: “Our message in This War of Mine is that war is not something that happens in a faraway land, in some fantasy kingdoms. That it’s something real and something that affects the people’s lives and makes people do things that they [normally] wouldn’t even think of.”

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1512367