We’ve driven GM and Lockheed Martin’s new Lunar Vehicle

MILFORD, MICH.—Over the radio, I’ve been instructed not to drive into the large crater near the south pole of the Moon. I had been circling the crest looking for a way in and as soon as mission control realized what I was about to do, it vetoed my heading. I turned away from the impact site and drove towards a hazy sun off in the distance determined to hit at least 25 km/h while battling the awkward effects of gravity one-sixth that of Earth.

General Motors and its partner Lockheed Martin are building a lunar rover without a NASA contract. They want to fly this vehicle to the Moon in support of the Artemis mission, because we’re going back to the Moon to drive and GM wants to be there first.

Another voice comes over the radio. “That’s five minutes. Please come to a stop and we’ll recenter the rig.”

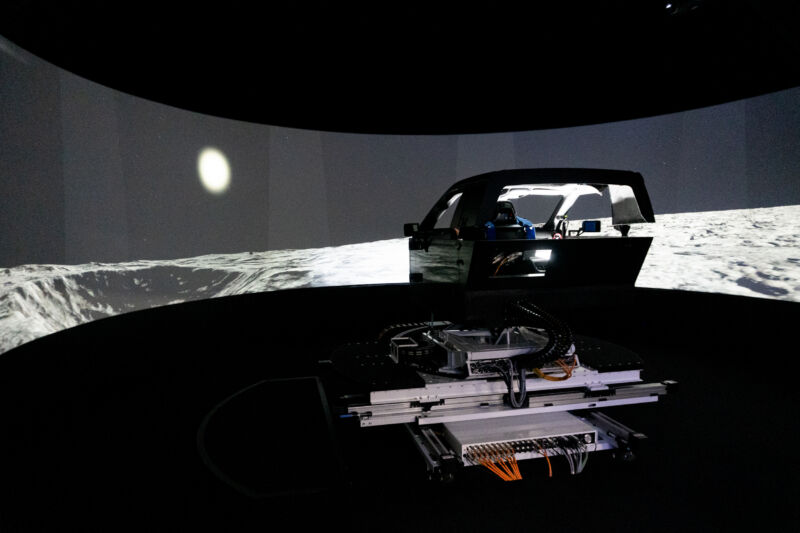

The rig is GM’s DIL (Driver in the Loop) simulator in the automaker’s Milford proving grounds in Milford, Michigan. The “vehicle” I’m sitting in—while driving on the Moon—has a typical GM interior but with a Corvette steering wheel; likely a nod to the automaker’s history of gifting astronauts the sports car. Meanwhile, the projected exterior is a premapped actual location on the Moon, exactly one square kilometer near the south pole of the Moon.

It’s a vast wasteland of gray with a diffused sun blazing in the sky. The monochromatic landscape makes it difficult to determine depth. It’s not an impossible task, but there are still moments when what seems like a small bump becomes something more substantial as it nears.

Determining whether to hit the space divot head-on or attempt to avoid it comes down to trying to understand and predict the physics of driving on our biggest satellite. With Lockheed’s help, GM has programmed the vehicle to drive and react to an environment with 1/6th the gravity of earth. There’s a floating quality to the suspension and ride. With less gravity and zero atmospheric downforce, everything is a potential launch into the air.

According to GM’s advanced program lead of vehicle dynamics, the system has a tendency to make people nauseous, as your brain wants everything to react the way it would with Earth’s gravity. The simulator’s Moon tuning doesn’t do what your body is expecting. Hence, a few queasy stomachs and the five-minute time limit. The team at GM has been working up towards hours-long excursions from their five-minute sessions.

In other words, we can’t drive all day on the Moon-sim, because there would be vomit.

The terrain itself is an electrostatically charged regolith of metal and glass; a fine dust of asteroid pieces that is like silt that attaches itself to absolutely everything and if gets into your electronics can cause some major issues. With Lockheed’s help, GM was able to recreate the surface of the Moon and its sharp, menacing dust.

The automaker also spoke to Apollo-era astronauts about their experience in space and on the Moon and what it was like driving the original lunar rover that still sits up there. This information helped tune the suspension but is also key to making sure that getting into and driving the rover is possible. Even simple tasks require some problem-solving ahead of putting a car on the lunar surface.

The astronauts will have limited movement in their suits, so egress needs to take into account the suit and backpack and allow someone to move in a way that doesn’t lead to a person hitting or getting caught on controls or the structure. Even seatbelts are a struggle thanks to the thick gloves.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1860672