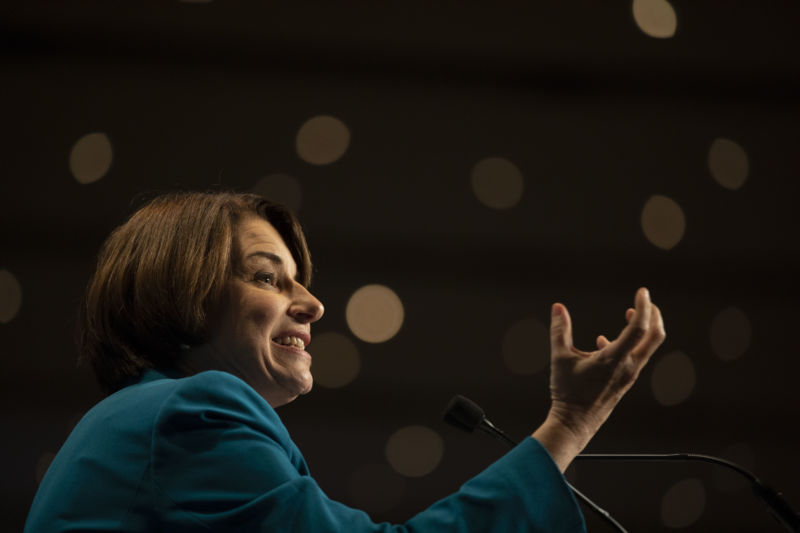

Why Amy Klobuchar just wrote 600 pages on antitrust

To promote her new book, Antitrust: Taking on Monopoly Power from the Gilded Age to the Digital Age, Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota gave a series of interviews this week, one of which was with me. She told me outright that our session was not her favorite of the tour—that honor went to her comedic exchange with Stephen Colbert a few days earlier, which she recounted to me line by line.

Nonetheless, I welcomed the chance to speak with her. Klobuchar has enjoyed a heightened profile since her presidential run and quick pivot to the eventual winner, Joe Biden, so she had her choice of book subjects to focus on. Ultimately, she produced 600 pages on the relatively arcane topic of antitrust law, a telling choice. Her goal is to make the subject less arcane, in hopes that a grassroots movement will support her effort to fortify and enforce the laws more vigorously. In the book, Klobuchar attempts to inspire readers with a history of the field, which in her rendering sprang from a spirited populist movement that included her own coal-mining ancestors. That’s why her book is stuffed with vintage political cartoons, typically portraying Gilded Age barons as bloated giants, hovering over workers like top-hatted Macy’s balloons. (Obviously those were the days before billionaires had Peloton.)

I’m not sure the downtrodden masses are about to become radicalized by thumbing through the 204 pages of footnotes in Antitrust. But as Klobuchar says, people are starting to realize that the wonderful products from sprightly startup founders have locked them into relationships with trillion-dollar, competition-killing behemoths. “In the beginning, consumers may have gotten a good deal, but history shows that in the end, monopolists do what monopolists want to do,” she says.

No wonder people feel helpless, especially when the government has done very little to curb consolidation and predatory practices in the past few decades. “Monopolies tend to have a lot of control, not just over consumers, but also over politics,” says Klobuchar. “People have just gotten beaten down. I wanted to show the public and elected officials that you’re not the first kids on the block with this. What do you think it was like back when trusts literally controlled everyone on the Supreme Court, or literally elected members of the Senate before they were elected by the public?”

I suppose it would be like… now. Where the power and political donations of big corporations have led to merger after merger, and where courts are dominated by jurists who cling to the pro-business dogma pioneered by Judge Robert Bork. (Klobuchar is excellent in describing how Bork provided a legal framework for anti-consumer conservatives to set the bar ridiculously high in enforcing competition.) Klobuchar admits that the current makeup of the Supreme Court, especially with corporate fanboy Neil Gorsuch in and Ruth Bader Ginsberg out, presents a considerable obstacle to reform. Her solution is to create new legislation that even our sitting judges will have to respect. That’s why the law she cosponsors has specific limits on the market power of big companies, including a ban on large mergers and acquisitions.

Klobuchar’s book comes just as her senate colleague, Josh Hawley of Missouri, released his own book about antitrust, as well as his own version of an antitrust law. In his treatise, Hawley expresses contempt for monopolies, a view that didn’t prevent him from accepting huge political donations from monopoly-defender Peter Thiel, who once wrote an op-ed for The Wall Street Journal headlined “Competition Is for Losers.” Hawley’s complaints are less rooted in history than Klobuchar’s and are seemingly motivated by his questionable belief that tech platforms stifle conservative speech. But even so, Klobuchar thinks there might be common ground.

Klobuchar takes pains to say she’s not anti-tech. “I am never saying, ‘Get rid of their products.’ But let’s have more of the products that give you more choices. You can keep one product, but it’s better to have other products, because we’re not China.” In other words, Facebook could keep it’s main app, but the public might benefit if Instagram and WhatsApp were not Mark Zuckerberg productions. She also notes that she’s concerned not only with tech, but also with other heavily consolidated industries like pharma.

While I have Klobuchar on the line, I ask her why legislators so often embarrass themselves in hearings with irrelevant partisanship, clueless technical questions, and time-wasting grandstanding. “Welcome to my life,” she says. “I get it—there’s going to be hearings that are irritating to people who know a lot. But that’s a great argument for tech to use because they don’t want this oversight.” She claims that lately the hearings have become more sophisticated and useful, citing a recent one she chaired that investigated the practices of Apple’s App Store and Google’s search results. Executives from smaller firms testified to apparently predatory practices from those trillion-dollar rivals. “We actually got to something,” she says.

I ask her to pick one thing that the tech companies have done in the past decade that she’d like to roll back. “I’m not going to pick one merger,” she says, but she does mention the Facebook acquisitions again, as well as Google’s preferential search functions. Oh, and she would have had companies build in better privacy. “I wouldn’t destroy those companies,” she says. “I would just do what antitrust laws are supposed to do, which is create a competitive environment and stop exclusionary behavior.”

At the end of her book, Klobuchar lists 44 suggestions for reform. The last is surprising: “Stop using the word antitrust.” The issues she addresses, she writes, are broader than those covered by that specific term. If you want to do that, I ask, why did you use that word as your book title? “Well, I thought antitrust was an interesting word,” she says. “It’s not only about this body of law; it’s also about not trusting anyone.”

Indeed, if Klobuchar had written a book about “trust,” it would be a much slimmer volume. And maybe that fact is an even bigger problem than the one posed by Big Tech.

This story originally appeared on wired.com.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1763506