Why Big Tobacco and Big Vape love comparing nicotine to caffeine

It feels intuitive to compare caffeine and nicotine, two drugs made by plants that can produce a bit of a buzz. But intuition isn’t the only thing at the root of that association: a concerted public relations effort by Big Tobacco has helped make it stick.

Industry documents, court testimony, and advertisements all show that the tobacco industry has been working for decades to equate nicotine with innocuous vices like coffee, tea, or gummy bears. The effort aims to erode damaging connections to substances with worse reputations, like heroin or cocaine. Now, that same caffeine-nicotine connection is flavoring the discourse about electronic cigarettes, too. “Chemically, nicotine is very similar to caffeine, and coffee is one of the most widely traded products in the world,” Juul co-founder James Monsees told The Mercury News in September 2018. “While people of all ages around the world enjoy coffee, nicotine has been heavily stigmatized.”

But nicotine and caffeine aren’t chemically similar, not really. When I covered the health effects of nicotine last year, I asked Adam Leventhal, director of the USC Health, Emotion, and Addiction Laboratory, how the two drugs compared. “They’re apples and oranges,” he told me, citing a long list of distressing nicotine withdrawal symptoms like anxiety, depression, irritability, and hunger. Clinical pharmacologist Neal Benowitz, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, says the same thing.

There is a link, in that smoking cigarettes may speed up the body’s metabolism of caffeine, so smokers can wind up drinking more coffee to maintain their caffeine buzz, Benowitz says. Nicotine may also boost the rewarding effects of other substances, like coffee, he says, “which means coffee might actually taste better to someone using nicotine.” So there’s a perception that coffee and cigarettes pair well. “And that’s what I think leads people to connect them,” Benowitz says.

Still, they’re very different drugs. Caffeine is a stimulant that works primarily by blocking the receptor for adenosine, a neurotransmitter that causes relaxation, Benowitz says. That can increase adrenaline and boost blood pressure. Nicotine, by contrast, can increase the release of multiple different neurotransmitters. That’s why for the people who use it, nicotine can act both as a stimulant and a relaxant in different contexts. “People can experience so many different things from nicotine depending on the situation in which they take it,” says Benowitz, who is not funded by any tobacco or e-cigarette companies, but who has consulted for pharmaceutical companies about smoking cessation medications. “It’s no accident that people become addicted,” he says.

That’s another place where nicotine and caffeine differ: the vast majority of people don’t become addicted to caffeine, says Benowitz, who describes addiction as “compulsive use and loss of control over drug use.” If a doctor tells someone to switch to decaf, most people can, despite the headache. But people have a harder time ignoring nicotine cravings when they’re trying to stop smoking, Benowitz says. “There’s much more positive reward and the withdrawal symptoms are more disruptive,” he says. “Nicotine and caffeine are different.”

Unwelcome associates

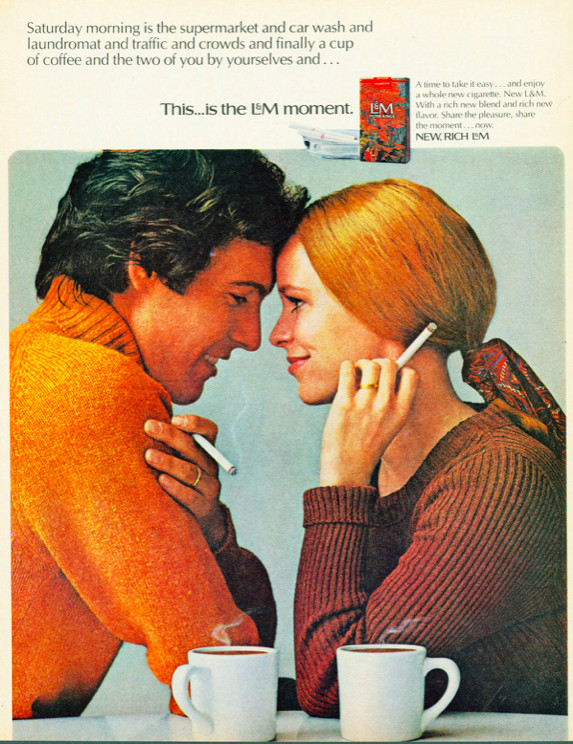

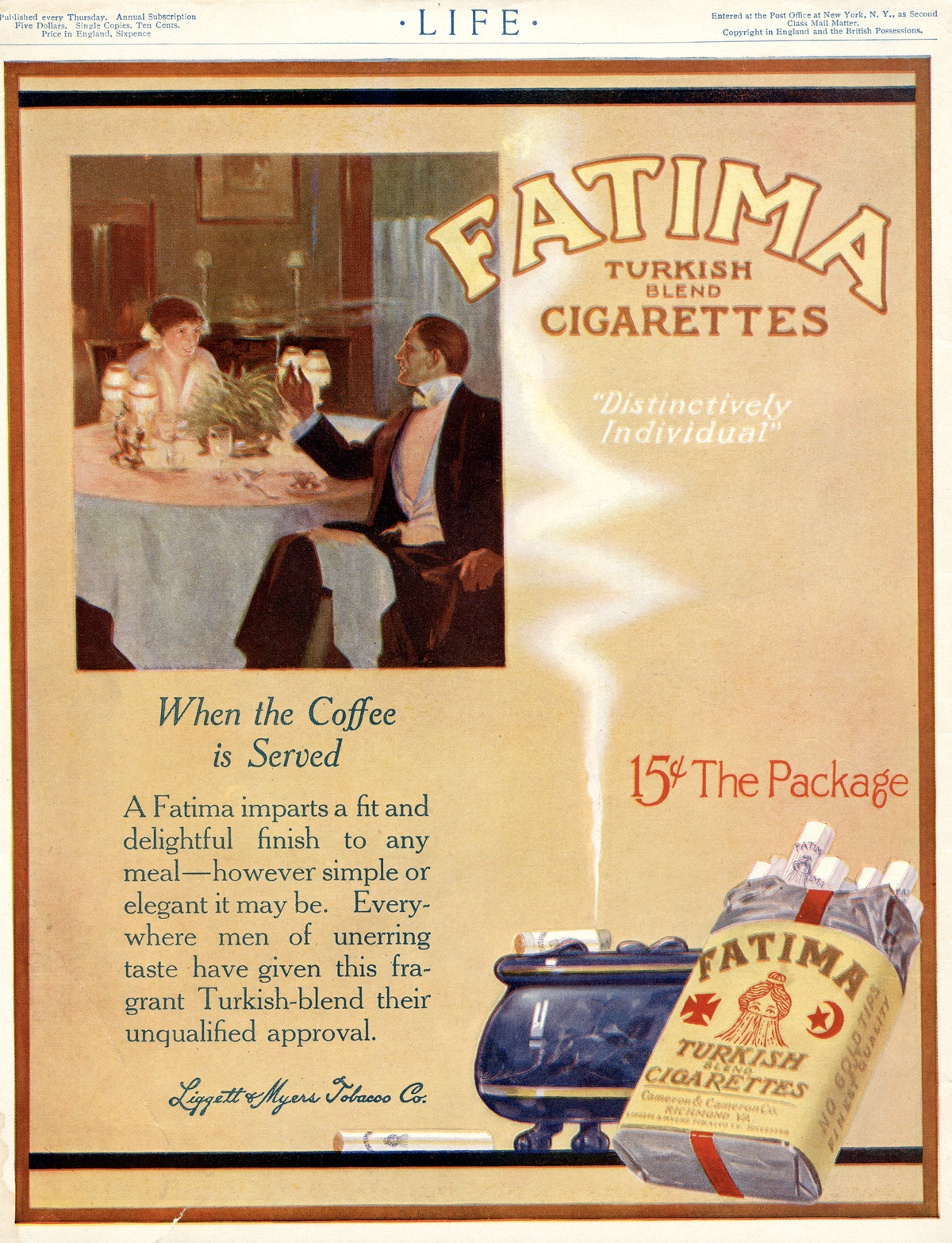

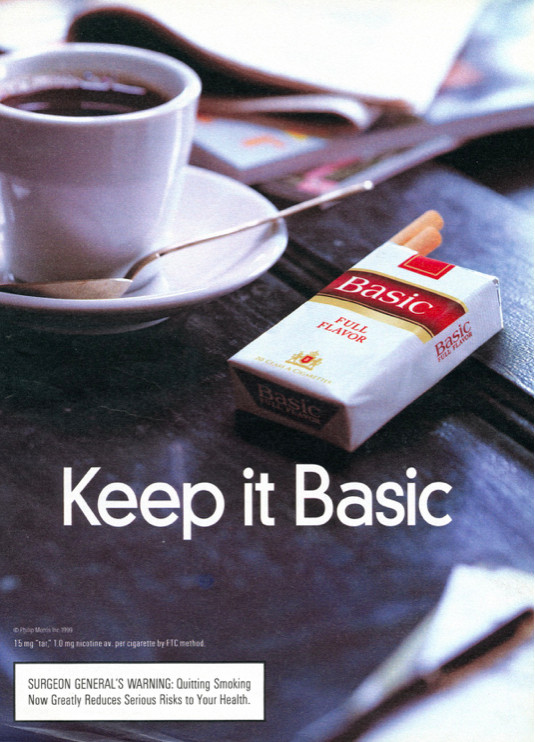

So if nicotine and caffeine really are apples and oranges, why do they show up together so often? Robert Jackler, a professor at Stanford University who studies tobacco marketing, has found ads going back to at least 1913 showing people smoking cigarettes while drinking coffee. Jackler thinks that the juxtaposition of cigarettes and coffee was part of a marketing push to make these tubes of tobacco leaves look essential to daily life. “One of the lead messages was that smoking adds pleasure to anything pleasurable you do — whether it’s romance or meals or coffee or liquor or fun at the beach,” Jackler says.

That strategy gained steam after the 1988 US Surgeon General’s report that called out nicotine as the drug responsible for addiction to cigarettes and other tobacco products, according to Pamela Ling, a professor at UCSF who studies tobacco industry marketing strategies. The worst part — at least, from an industry perspective — was that the Surgeon General said, “The pharmacologic and behavioral processes that determine tobacco addiction are similar to those that determine addiction to drugs such as heroin and cocaine.”

Those weren’t bedfellows that the tobacco industry wanted. “And so they started this big campaign in the ‘80s to say, ‘No, nicotine is not like heroin or cocaine. It’s like caffeine or chocolate. It’s a benign substance,’” Ling says. That campaign included a concerted public relations push. By analyzing internal documents from tobacco company RJ Reynolds, Ling discovered that their communications strategy encouraged caffeine analogies. “Caffeine use is socially accepted — might enhance social acceptance of nicotine,” a 1993 RJ Reynolds document says.

Some of these analogies were disseminated through an industry-funded proxy called Associates for Research in the Science of Enjoyment (ARISE), according to a 2007 study published in the European Journal of Public Health by tobacco researcher Elizabeth Smith. Smith, an adjunct professor at UCSF, dug through news stories and internal tobacco company documents looking for references to ARISE. Created after that 1988 report by the US Surgeon General, Smith’s paper says, “ARISE’s message was that ‘a little of what you fancy can do you good.’”

Under the guise of promoting “objectivity” and “debate,” ARISE sowed doubt about the addictiveness and harm of smoking through conferences and opinion polls. These conferences, Smith says, gave the industry an excuse to put out grabby press releases about tobacco as pleasurable rather than addictive. “It provided a way for the industry to get journalists to tell this kind of story and spread this idea that tobacco isn’t as bad for you as everyone’s been saying,” she says. “The fact that it’s complete bullshit doesn’t really matter in the long run.”

Of the hundreds of articles Smith uncovered that mentioned ARISE between 1989 and 2005‚ 483 explicitly mentioned tobacco. And of those, more than 94 percent also mentioned chocolate, coffee, tea, and alcohol. The common refrain from ARISE members quoted in news articles was that a “favourite treat, such as a cup of tea or coffee, a glass of wine or beer, a cigarette or a bar of chocolate, reduces stress and helps people relax.” This minimizes the health risks of cigarette addiction and instead frames smoking as an occasional, potentially beneficial, indulgence. The trouble is, Smith says, “tobacco isn’t like that.”

It’s an argument that the industry has stuck to again and again as it’s defended itself against lawsuits. One expert witness compared nicotine to caffeine — and also to fingernail chewing — in order to dismiss nicotine addiction as simply a habit, according to a 2007 review of the industry’s legal strategies. Another said, “Nicotine and caffeine are fundamentally different from addicting drugs like heroin and cocaine.” The repetition of the claim doesn’t make it true — but it does help it stick.

Same story, new storytellers

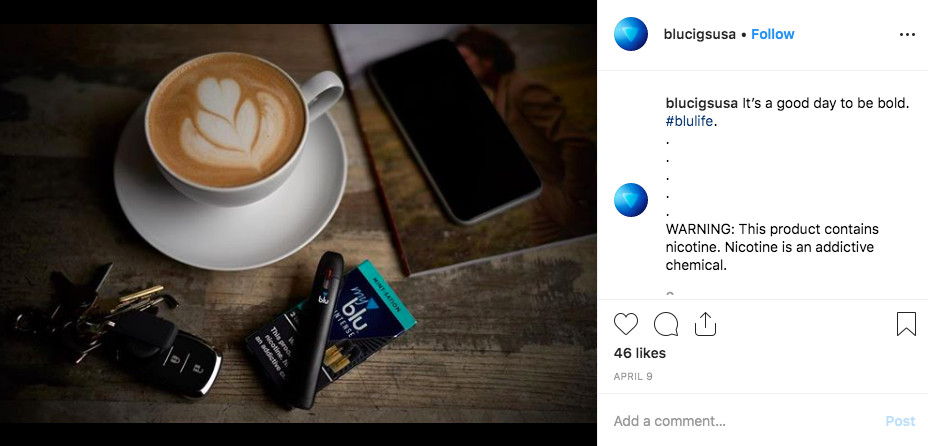

The rise of the e-cigarette industry has added another layer of complexity to the situation. The industry separates nicotine from tobacco to make its products, even as it becomes more enmeshed with the tobacco industry itself. But even with new ways to deliver nicotine, the e-cigarette business still appears to be using the same playbook to cast nicotine as the misunderstood chemical sibling of caffeine. Jackler has discovered that the link shows up subtly in industry advertisements that pair e-cigarettes and coffee in the same frame. Coffee-flavored vape juice adds a new, strange connection to the mix.

Jackler thinks that part of this juxtaposition is a callback to those traditional tobacco industry advertisements that focus on the pleasure that smoking adds to everyday moments, like having a cup of coffee. When the e-cigarette industry does it, he says, “It’s to associate vaping with pleasurable moments in the day.”

Juul has since pulled their ads from social media, and they say they’re careful to toe the line when it comes to alerting people about nicotine in their products. “JUULpods have always indicated that they contain nicotine,” a spokesperson told The Verge in an email. “When FDA required all e-cigarette manufacturers to place additional warnings on its packaging and in its advertising, JUUL Labs promptly complied with those requirements.” And British American Tobacco, the company behind the Vype brand of vapes that has also combined coffee and vape imagery on social media, says: “We know that there could be certain points in the day that some of our consumers will want to enjoy one of our products — and vaping whilst having a coffee is one such example of this. This is factually reflected in the imagery. To be clear, this is not about comparing nicotine to caffeine.”

But vaping heavy-hitters have made the caffeine-nicotine link explicitly, too — like when Juul’s co-founder bemoaned the stigmatization of nicotine compared to caffeine in his conversation with The Mercury News. In its policy position, an advocacy group called the Smoke-Free Alternatives Trade Association, calls nicotine, “a naturally occurring and relatively harmless substance that has roughly the equivalent danger to the individual’s health as caffeine.” The claims echo former NJOY CEO Craig Weiss, who said in a 2013 CNBC appearance: “Pharmacologically, it’s very similar to caffeine. It’s a stimulant that provides energy but in the case of nicotine, it’s also a relaxing and calming effect.” (The anchor pushed back: “As a smoker, I adore the fact that you’re prepared to say that, actually, nicotine is better for you than caffeine. Come on.”)

Jackler and Ling think this push to lump nicotine and caffeine together is part of an ongoing effort to downplay the risks of e-cigarettes. “I think it’s pretty well accepted that the most dangerous way to use nicotine is through smoking cigarettes,” Ling says. Electronic cigarettes are generally considered less risky than the conventional kind, but they’re not risk-free, particularly for non-smokers and young people. Researchers are still investigating the long-term health effects, but different labs have drawn links between e-cigarettes and potential heart problems, lung irritation, wheezing, and, of course, nicotine addiction. There’s also an ongoing debate about the degree to which e-cigarettes really help people quit smoking.

The rise of e-cigarettes led the industry back to this old idea, Ling says. But where trivializing nicotine addiction by comparing it to caffeine was once part of the Big Tobacco’s larger strategy to deny the danger altogether, now it’s part of an effort to promote the idea of “clean nicotine.” “If e-cigarettes are positioned as a safe way to use nicotine, then the e-cigarette companies are going to embrace this idea that nicotine itself isn’t harmful and might be beneficial,” she says. “In the end, both the tobacco industry in the ‘80s and the e-cigarette industry now both benefit from arguing that nicotine addiction is not a big deal.” That means that even as cigarette smoking continues to decline in the US, the rebranded nicotine industry may keep trying to sell this very old story to a new audience — even though there’s nothing to back up the buzz.

https://www.theverge.com/2019/4/26/18513312/vape-tobacco-big-companies-nicotine-caffeine-comparison-drugs-chemicals