Why game archivists are dreading this month’s 3DS/Wii U eShop shutdown

In just a few weeks, Nintendo 3DS and Wii U owners will finally completely lose the ability to purchase new digital games on those aging platforms. The move will cut off consumer access to hundreds of titles that can’t legally be accessed any other way.

But while that’s a significant annoyance for consumers holding onto their old hardware, current rules mean it could cause much more of a crisis for the historians and archivists trying to preserve access to those game libraries for future generations.

“While it’s unfortunate that people won’t be able to purchase digital 3DS or Wii U games anymore, we understand the business reality that went into this decision,” the Video Game History Foundation (VGHF) tweeted when the eShop shutdowns were announced a year ago. “What we don’t understand is what path Nintendo expects its fans to take, should they wish to play these games in the future.”

DMCA headaches

Libraries and organizations like the VGHF say their game preservation efforts are currently being hampered by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), which generally prevents people from making copies of any DRM-protected digital work.

The US Copyright Office has issued exemptions to those rules to allow libraries and research institutions to make digital copies for archival purposes. Those organizations can even distribute archived digital copies of items like ebooks, DVDs, and even generic computer software to researchers through online access systems.

But those remote-access exemptions explicitly leave out video games. That means researchers who want to access archived game collections have to travel to the physical location where that archive resides—even if the archived games themselves were never distributed on physical media.

That kind of access restriction is just “not reasonable” for video games, as VGHF co-director Kelsey Lewin put it in a conversation with Ars Technica. Even if an institution like The Strong Museum of Play obtained and maintained copies of all current 3DS and Wii U eShop games, “the only way anyone could ever legally play or study [those games] is if they flew to Rochester, signed a consent form, and sat in the premises playing it,” Lewin points out.

VGHF Library Director Phil Salvador pointed out just how impractical that kind of on-site access requirement can be for game researchers. “Right now, if a researcher wants to study an out-of-release, 50-hour-long RPG at a library, they might have to book days or even weeks of travel, lodging, research leave, and child care,” he told Ars. “Requiring researchers to access games on-site can be prohibitive. It discourages use of institutional game collections, and in turn, it discourages institutions from maintaining them. Thankfully, emulation-as-a-service technology already exists that, if permitted, could allow for secure, remote access to video game materials.”

Fear of an “online arcade”

Beyond stopping consumers from purchasing digital 3DS and Wii U games, the VGHF says Nintendo is also helping to stop this kind of easy research access to archival copies. As a member of the Entertainment Software Association (ESA), Nintendo “actively funds lobbying that prevents even libraries from being able to provide legal access to these games,” the VGHF said. “Not providing commercial access is understandable, but preventing institutional work to preserve these titles on top of that is actively destructive to video game history.”

Indeed, the ESA was one of the main groups arguing against a DMCA exemption for off-site access to library game archives during wide-ranging arguments in front of The US Copyright Office in 2021.

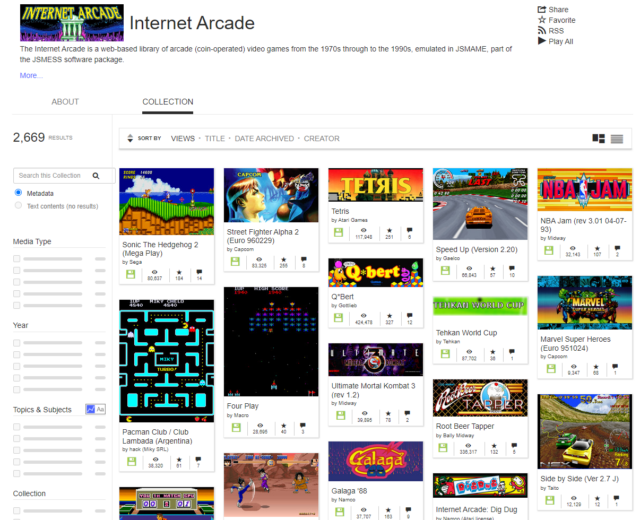

During those arguments, ESA lawyer Steve Englund expressed the industry lobbying group’s concerns that the exemption, as proposed, would allow a library to “put emulated games up online for a public audience” with no meaningful access restrictions. Englund pointed to The Internet Archive’s emulated game collections as an example of the kind of “online arcade” that goes beyond “research” purposes and allows for “recreational play by patrons of public libraries.” That kind of wide-ranging access could cause “potential… market harm” to the ESA’s copyright holders, Englund said.

Researchers at the hearing called those concerns overblown. Stanford University media curator Henry Lowood said that institutions like his were not interested in providing “unrestricted access to all” and would not “be putting anything up on the open web. This will be a closed system with authenticated users, and pretty much restricted to the researchers and students or other groups that we’ve mentioned earlier.”

But even those kind of access limitations weren’t necessarily comforting to Englund and the ESA. “College students are important consumers of video games,” Englund argued. “Merely saying that somebody is a student at a university who has been identified as being enrolled at the university ought to be able to access emulation is not a comforting message.”

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1924315