Why we need emoji representing people with disabilities

When Carrie Wade first heard the news that Apple was proposing emoji to represent people with disabilities, she felt happy — then immediately curious about what sorts of emoji Apple had come up with. Wade has cerebral palsy and works at the American Association of People with Disabilities. To finally have emoji made specifically for people like her felt like an important step forward.

“Of course there are going to be people who say this is inconsequential and it doesn’t matter,” Wade tells The Verge. “But this is one of those instances of small-scale media representation that is there now and wasn’t there before. That kind of progress is always a good thing.” She was also “pleasantly surprised” to see the service dog emoji.

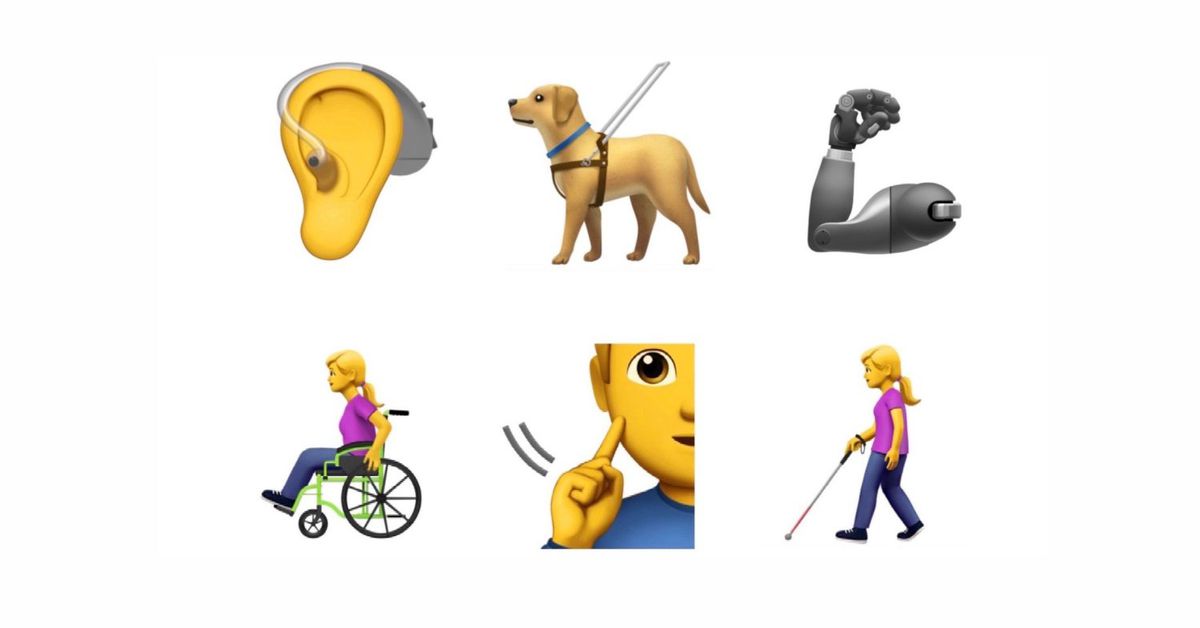

Apple submitted a proposal for the 13 new emoji to the Unicode Consortium a couple of weeks ago; they include a prosthetic arm and leg, hearing aids, as well as people using sign language and a wheelchair. The emoji were well received, although several people in the community pointed out that they are just a starting point.

“Really when you look at diversity among disabilities, this represents part of the community but not all,” says Rachel Byrne, VP of projects and programs at the Cerebral Palsy Foundation. But, she adds, “it’s wonderful to have diversity within the emojis.” (In its proposal, Apple acknowledged the emoji are “not meant to be a comprehensive list.”)

Apple worked with the Cerebral Palsy Foundation, as well as the American Council of the Blind and National Association of the Deaf, to develop the emoji. Ideas were bounced back and forth, and the results are exciting, according to Tony Stephens, director of advocacy and governmental affairs of the American Council of the Blind.

Stephens says he’s excited that the emoji include a person with a white cane, the universal symbol for the blind, instead of a person wearing sun glasses, which is more of a stereotype. Having a white cane emoji can also help educate people about what the cane means, so that drivers can pay more attention when they see a pedestrian using one. “It brings awareness to the diversity of people that are using smartphones these days,” he says.

Representation has long been an issue in media. Movies and TV shows often resort to stereotypes when dealing with characters with disabilities: blind people are often portrayed as having heightened senses, like a better hearing, Stephens says. Disability is also often linked to tragedy on the screen, says Wade.

There have been improvements lately: Stephens points to an M&T Bank ad casually including a blind woman with a guide dog, while Byrne mentions the TV show Speechless. But there’s still a long way to go, and the Apple emoji are a step in the right direction. “Having accessibility and inclusion of all types be a priority in tech is a huge issue,” Wade says, “so I’m hoping, in whatever small way, that this signals progress and also it just means that people can have fun and have more options for how they express themselves.”

As we wait for the emoji to be approved, which could happen as soon as this month, The Verge spoke with Wade about what she thinks of the emoji, how they can be improved, and why they matter.

The interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

What do you think of the emoji?

I think it’s a great development. Emojis are sort of an emerging language, especially among younger generations, so it’s always great to watch those formats sort of progress, to be more inclusive and not just be the same icons we’ve all been seeing since we were 12-year-olds and first starting out on the internet. Of course, there are shortcomings: disability is too big of an umbrella to be fully encapsulated into any sort of emoji. But I thought it was good that those shortcomings were acknowledged up front. So while there’s certainly room for improvement, I’m excited to see this progress. Hopefully everything will be approved and they will be well received and frequently used, so that the further inclusion that wasn’t part of this first round will be possible in the future.

What are the shortcomings?

There are certain disabilities that are largely invisible, that can be difficult to illustrate for exactly that reason, [like] any sort of chronic illnesses, psychiatric disabilities, developmental disabilities. The disability community is vast and there are folks with disability in every other demographic. Disability doesn’t just look one way, it doesn’t just feel one way, it doesn’t just manifest one way in somebody’s body or mind. So expanding the definition of disability beyond readily apparent physical disabilities to include a larger swath… that’s definitely some progress that we need everywhere, including emoji options and technological communication.

Why is it important to have emoji representing people with disabilities?

This is a language that more and more people are using to communicate with each other every day, and the idea that there are actual people represented in emojis means that every community of people should be represented. People might argue that it’s not as important to have a disabled emoji versus a character in a TV show, but I think that it is important because people my age and younger — I’m 29 — we’re using these things to communicate with each other all the time. It’s like a second language on our phones and I think to not see yourself represented there, it says a lot.

What are the biggest challenges in getting representation in media?

I think the biggest challenges with representation [have to do with] a sort of stigma and a misunderstanding of what disability means in people’s lives. Up until now, there’s been this one-sided illustration of what having a disability can mean for your life: the vast majority of media — although it is changing — have had this tragic element and sort of imply that whatever else is going on in your life, if you have a disability, in some level you must be sad about it. As somebody with a lifelong disability, I completely understand those feelings. There is some level of frustration and difficulty that comes with having a disability. But I think that having media double down on this tragic narrative really does the rest of us — real folks with disability in the world — a huge disservice.

There are different ways of looking at disability that aren’t based in tragedy. People who create media that’s not necessarily super inclusive; it’s not that they aren’t well meaning, it’s just that they don’t have a very holistic and wide-ranging view of what disability means. Those problems can be in part rectified with hiring more actual disabled people both behind and in front of the camera, as creators and as performers. I would say, changing the voices in the room can make disability inclusion more of a priority from the beginning. Emojis in their own small way are an illustration of that and there’s certainly room to move forward after this. But I think it’s a great effort to start.

https://www.theverge.com/2018/4/3/17193020/apple-emojis-disability-representation-media-carrie-wade-interview