X-ray analysis confirms forged date on Lincoln pardon of Civil War soldier

A document containing President Abraham Lincoln’s signed pardon of a Civil War soldier has been the source of much controversy since its 1998 discovery, after historians concluded that the date had likely been altered to make the document more historically significant. A new analysis by scientists at the National Archives has confirmed that the date was indeed forged (although the pardon is genuine), according to a November paper published in the journal Forensic Science International: Synergy. The authors also concluded that there is no way to restore the document to its original state without causing further damage.

Thomas Lowry is a retired psychiatrist turned amateur historian, specializing in military records of the Civil War, and has authored numerous Civil War histories. Back in 1998, he and his wife Beverly were combing through a trove of rarely studied courts martial at the National Archives, carefully indexing the documents. At the time, there were no security cameras in the room, and Archive staffers knew the Lowrys and trusted them. The couple discovered some 570 documents with Lincoln’s signature.

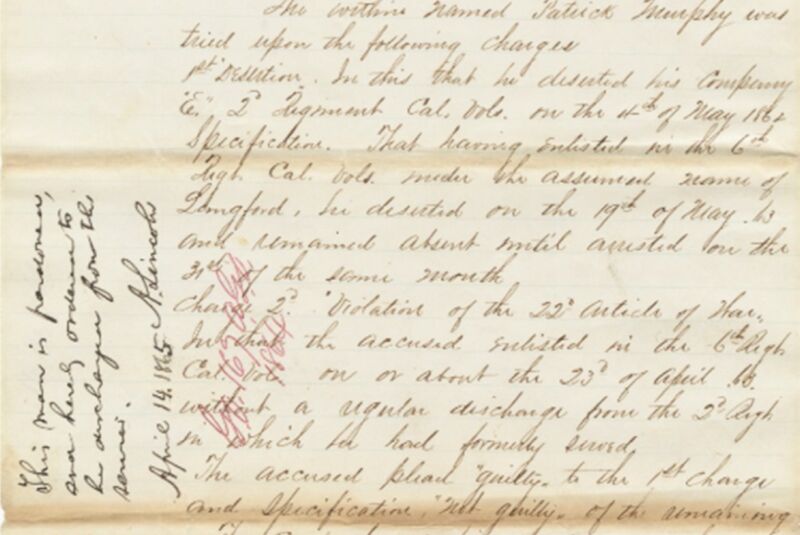

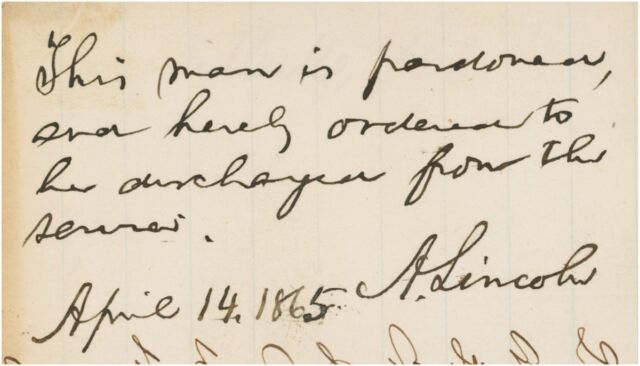

Among then was a pardon for a Civil War solider in the Union Army named Patrick Murphy, a private who had been court-martialed for desertion and condemned to death. The pardon is written perpendicularly in the left margin of a letter dated September 1, 1863, requesting a pardon for Murphy. Lincoln’s statement reads, “This man is pardoned and hereby ordered to be discharged from the service.” It was signed “A. Lincoln.”

It was the date that made the document significant: April 14, 1865, meaning the pardon was likely one of the last official acts of President Lincoln, since he was assassinated later that same day at Ford’s Theater in Washington, DC. The pardon was broadly interpreted as evidence for a historical narrative about the president’s compassionate nature: i.e., his last act was one of mercy. The discovery made headlines and brought Lowry considerable renown.

After its discovery, the Murphy pardon was exhibited in the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom in the National Archives building. But an archivist named Trevor Plante became suspicious of the document, noting that the ink on the “5” in “1865” was noticeably darker. It also seemed as if another number was written underneath it. Then Plante consulted a seminal collection of Lincoln’s writings from the 1950s. The pardon was there, but it was dated April 14, 1864—a full year before Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth. Clearly the document had been altered sometime between the 1950s and 1998 to make the pardon more historically significant.

Investigators naturally turned to the man who made the discovery for further information. They began corresponding with Lowry in 2010. Initially, Lowry seemed cooperative, but when he learned about the nature of the investigation, he stopped communicating with the Office of the Inspector General, thereby arousing suspicion. So the investigators knocked on the historian’s door one January morning in 2011 for an interview.

Shortly thereafter, the National Archives released a statement that Lowry had confessed to altering the date on the pardon. Lowry confessed to bringing a fountain pen into the research room, along with fade proof, pigment-based ink, and changing the “4” in “1865” to a “5.” Lowry couldn’t be charged with any crime because the statute of limitations for tampering with government property had run out, but he was barred from the National Archives for life.

But there’s a twist: Lowry soon recanted, claiming he had signed the confession under duress from the National Archives investigators. He claimed the investigators assured him it would never be publicized and he would not suffer any consequences. “I consider these records sacred,” he told the Washington Post at the time. “It is entirely out of character for me. I am a man of honor.” His wife suggested a more likely culprit was a former Archives staffer. (The agency denied that allegation.)

Apart from the question of Lowry’s innocence or guilt, conservators at the National Archives were keen to study the altered document more closely, and to learn whether the original date might be restored by removing the forged “5.” Plante told the Washington Post he was not optimistic, because “Lowry purposely used ink that’s going to last a very long time.” The ink appeared to be iron gall ink, consistent with the period.

The National Archives has a cutting-edge heritage science laboratory, with expertise in a broad range of analytical techniques that have become popular in cultural forensics circles. In the case of Lincoln’s pardon, the team closely examined the date and signature under visible and ultraviolet light, as well as using XRF analysis to compare the elemental composition of the ink.

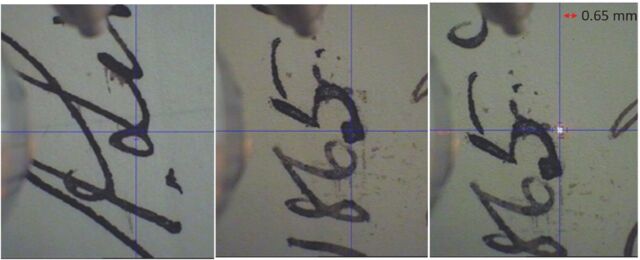

An examination of the “1854” under magnification and reflective fiber optic lighting showed the ink used to write the “5” was indeed different in overall color compared to the other numbers in the date. Furthermore, “Vestiges of ink from a scratched away number can be seen below and beside the darker ‘5,’ as well as smeared across the paper,” the authors wrote.

Additional analysis under raking light—a technique that accentuates hills and valleys in the paper texture—revealed abrasions to the paper under and around the “5” that were not observed anywhere else on the document. The team also determined that the paper around the “5” is thinner than everywhere else, and that ink residue of the scratched-away “4” were caught in the abraded paper fibers, clearly visible using transmitted light microscopy.

Then the team examined the verso of the document, since iron gall ink is known to penetrate the back of paper, making it possible to see the image of the front text on the back of the sheet. They noted that the penetration of the “5” was noticeably more intense than for the other numbers, which the authors attribute to “the darker, blacker ink being applied more heavily to the paper already thinned when the original ink of the ‘4’ was scratched away.”

Finally, the National Archives team used non-invasive XRF analysis to identify which elements were present in the ink. They found the expected presence of potassium and sulfur (common to iron gall inks) in the ink used in the “L” of Lincoln’s signature and the “8” in the date. They also found calcium, likely added to the paper as filler when it was manufactured.

They compared that ink to the ink used to write the “5” and found that the overall signals for iron, potassium, and sulfur were much higher for the latter. This is not due to the “5” ink having a thicker application. The ratios of iron to sulfur, and iron to potassium, are not the same, either. “There is strong support that the ink was not written by Lincoln but at a more recent time with a thicker application, after Lincoln’s original ‘4’ was removed,” the authors concluded.

This analysis also confirmed Plante’s pessimism about the prospect of removing the forged “5,” thereby restoring the pardon to its original state. “Any further intervention or attempted removal of the new ‘5’ could not be done selectively and would only further damage the original materials of the historical document,” the authors wrote.

DOI: Forensic Science International: Synergy, 2021. 10.1016/j.fsisyn.2021.100210 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1821962