It was 1983, and Acorn Computers was on top of the world. Unfortunately, trouble was just around the corner.

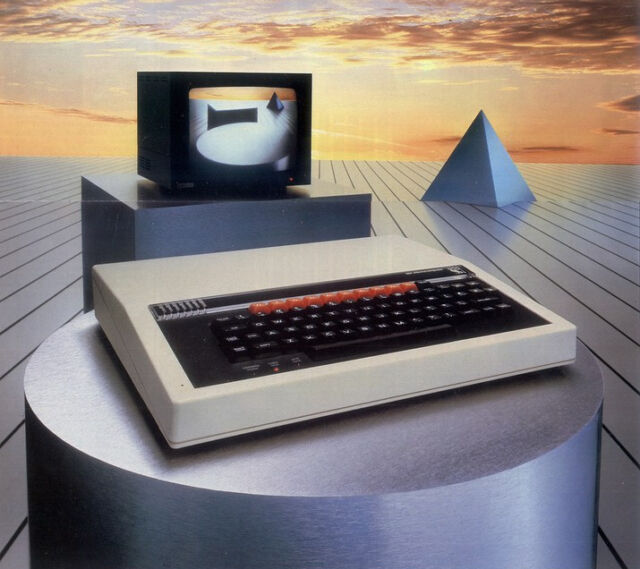

The small UK company was famous for winning a contract with the British Broadcasting Corporation to produce a computer for a national television show. Sales of its BBC Micro were skyrocketing and on pace to exceed 1.2 million units.

But the world of personal computers was changing. The market for cheap 8-bit micros that parents would buy to help kids with their homework was becoming saturated. And new machines from across the pond, like the IBM PC and the upcoming Apple Macintosh, promised significantly more power and ease of use. Acorn needed a way to compete, but it didn’t have much money for research and development.

A seed of an idea

Sophie Wilson, one of the designers of the BBC Micro, had anticipated this problem. She had added a slot called the “Tube” that could connect to a more powerful central processing unit. A slotted CPU could take over the computer, leaving its original 6502 chip free for other tasks.

But what processor should she choose? Wilson and co-designer Steve Furber considered various 16-bit options, such as Intel’s 80286, National Semiconductor’s 32016, and Motorola’s 68000. But none were completely satisfactory.

In a later interview with the Computing History Museum, Wilson explained, “We could see what all these processors did and what they didn’t do. So the first thing they didn’t do was they didn’t make good use of the memory system. The second thing they didn’t do was that they weren’t fast; they weren’t easy to use. We were used to programming the 6502 in the machine code, and we rather hoped that we could get to a power level such that if you wrote in a higher level language you could achieve the same types of results.”

But what was the alternative? Was it even thinkable for tiny Acorn to make its own CPU from scratch? To find out, Wilson and Furber took a trip to National Semiconductor’s factory in Israel. They saw hundreds of engineers and a massive amount of expensive equipment. This confirmed their suspicions that such a task might be beyond them.

Then they visited the Western Design Center in Mesa, Arizona. This company was making the beloved 6502 and designing a 16-bit successor, the 65C618. Wilson and Furber found little more than a “bungalow in a suburb” with a few engineers and some students making diagrams using old Apple II computers and bits of sticky tape.

Suddenly, making their own CPU seemed like it might be possible. Wilson and Furber’s small team had built custom chips before, like the graphics and input/output chips for the BBC Micro. But those designs were simpler and had fewer components than a CPU.

Despite the challenges, upper management at Acorn supported their efforts. In fact, they went beyond mere support. Acorn co-founder Hermann Hauser, who had a Ph.D. in Physics, gave the team copies of IBM research papers describing a new and more powerful type of CPU. It was called RISC, which stood for “reduced instruction set computing.”

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1879525