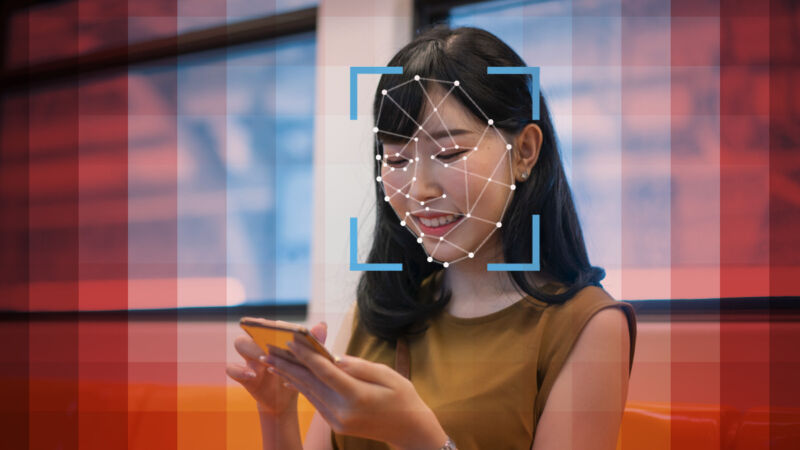

OpenAI has been testing its multimodal version of GPT-4 with image-recognition support prior to a planned wide release. However, public access is being curtailed due to concerns about its ability to potentially recognize specific individuals, according to a New York Times report on Tuesday.

When OpenAI announced GPT-4 earlier this year, the company highlighted the AI model’s multimodal capabilities. This meant that the model could not only process and generate text but also analyze and interpret images, opening up a new dimension of interaction with the AI model.

Following the announcement, OpenAI took its image-processing abilities a step further in collaboration with a startup called Be My Eyes, which is developing an app to describe images to blind users, helping them interpret their surroundings and interact with the world more independently.

The New York Times report highlights the experiences of Jonathan Mosen, a blind user of Be My Eyes from New Zealand. Mosen has enjoyed using the app to identify items in a hotel room, like shampoo dispensers, and to accurately interpret images on social media. However, Mosen expressed disappointment when the app recently stopped providing facial information, displaying a message that faces had been obscured for privacy reasons.

Sandhini Agarwal, an OpenAI policy researcher, confirmed to the Times that privacy issues are why the organization has curtailed GPT-4’s facial recognition abilities. OpenAI’s system is currently capable of identifying public figures, such as those with a Wikipedia page, but OpenAI is concerned that the feature could potentially infringe upon privacy laws in regions like Illinois and Europe, where the use of biometric information requires explicit consent from citizens.

Further, OpenAI expressed worry that Be My Eyes could misinterpret or misrepresent aspects of individuals’ faces, like gender or emotional state, leading to inappropriate or harmful results. OpenAI aims to navigate these and other safety concerns before GPT-4’s image analysis capabilities become widely accessible. Agarwal told the Times, “We very much want this to be a two-way conversation with the public. If what we hear is like, ‘We actually don’t want any of it,’ that’s something we’re very on board with.”

Despite these precautions, there have also been instances of GPT-4 confabulating or making false identifications, underscoring the challenge of making a useful tool that won’t give blind users inaccurate information.

Meanwhile, Microsoft, a major investor in OpenAI, is testing a limited rollout of the visual analysis tool in its AI-powered Bing chatbot, which is based on GPT-4 technology. Bing Chat has recently been seen on Twitter solving CAPTCHA tests designed to screen out bots, which may also delay the wider release of Bing’s image-processing features.

Google also recently introduced image analysis features into its Bard chatbot, which allows users to upload pictures for recognition or processing by Bard. In our tests of the feature, it could solve word-based CAPTCHAs, although not perfectly every time. Already, some services such as Roblox use very difficult CAPTCHAs, likely to keep ahead of similar improvements in computer vision.

This kind of AI-powered computer vision may come to everyone’s devices sooner or later, but it’s also clear that companies will need to work out the complications before we can see wide releases with minimal ethical impact.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1954677