On October 29, 1969, at 10:30pm Pacific Time, the first two letters were transmitted over ARPANET. And then it crashed. About an hour later, after some debugging, the first actual remote connection between two computers was established over what would someday evolve into the modern Internet.

Funded by the Advanced Research Projects Agency (the predecessor of DARPA), ARPANET was built to explore technologies related to building a military command-and-control network that could survive a nuclear attack. But as Charles Herzfeld, the ARPA director who would oversee most of the initial work to build ARPANET put it:

The ARPANET was not started to create a Command and Control System that would survive a nuclear attack, as many now claim. To build such a system was, clearly, a major military need, but it was not ARPA’s mission to do this; in fact, we would have been severely criticized had we tried. Rather, the ARPANET came out of our frustration that there were only a limited number of large, powerful research computers in the country, and that many research investigators, who should have access to them, were geographically separated from them.

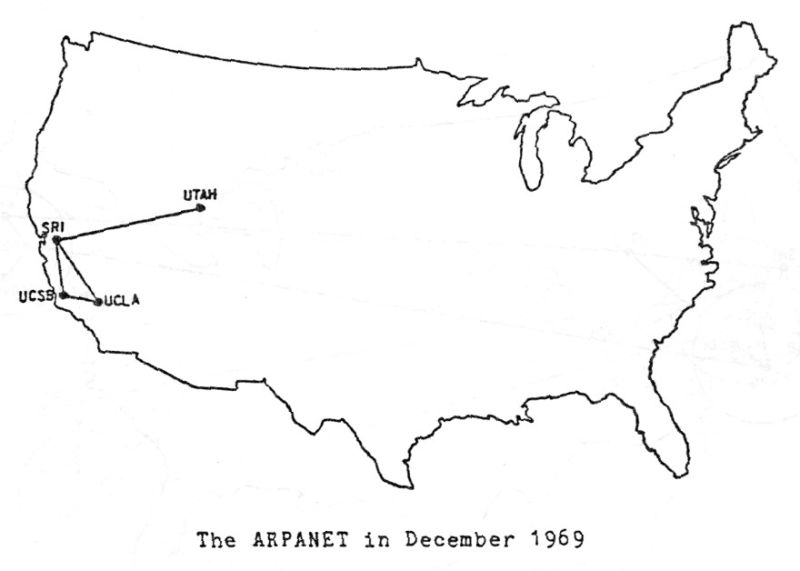

In its infancy, ARPANET had but four “nodes”:

- The University of California-Los Angeles’ Network Measurement Center, with its SDS Sigma 7 computer;

- Stanford Research Institute’s Network Information Center, with its SDS 940 computer running NLS (an early hypertext system and precursor to the World Wide Web);

- The University of California, Santa Barbara’s Culler-Fried Interactive Mathematics Center, with its IBM 360/75 running OS/MVT; and

- The University of Utah School of Computing, with its Digital Equipment Corp PDP-10 running the TENEX operating system.

Rather than being directly connected, the computers were connected via Interface Message Processors (IMPs), which were the first network routers. This would allow additional systems to be added as nodes to the network at each site as it evolved and grew. This idea came from physicist Wesley Clark, who is also credited with designing the LINC, the world’s first personal computer.

The first letters transmitted, sent from UCLA to Stanford by UCLA student programmer Charley Kline, were “l” and “o.” On the second attempt, the full message text, login, went through from the Sigma 7 to the 940. So, the first three characters ever transmitted over the precursor to the Internet were L, O, and L.

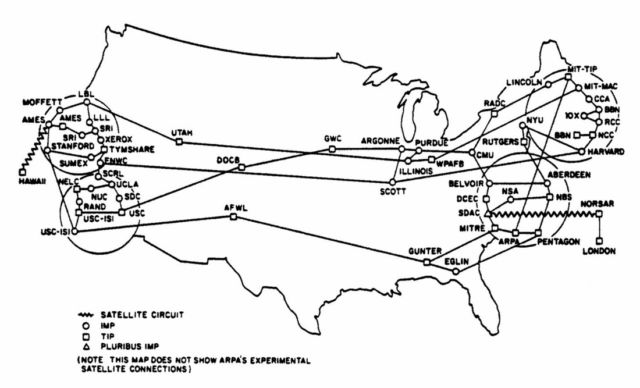

By the time I was first exposed to ARPANET, it had grown significantly, but it was still primarily a connection between researchers and military organizations. ARPANET was operated by the military until 1990, and until then, using the network for anything other than government-related business and research was illegal. By that time, ARPANET was largely being supplanted by the National Science Foundation Network (NSFnet). Even though the Defense Department had split off its own networks as MILNET in the mid-1980s, parts of the military still referred to its network connections as ARPANET in many internal documents into the early 1990s, as I found when I was working as a network engineering contractor at Army Test Lab at Aberdeen in 1992.

When it was shut down, Vinton Cerf, one of the fathers of the modern Internet, wrote a poem in ARPANET’s honor:

It was the first, and being first, was best,

but now we lay it down to ever rest.

Now pause with me a moment, shed some tears.

For auld lang syne, for love, for years and years

of faithful service, duty done, I weep.

Lay down thy packet, now, O friend, and sleep.

Without ARPANET, there would have been no Internet. So pour one out for the original tonight if you happen to be basking in the Internet’s glow.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1593459