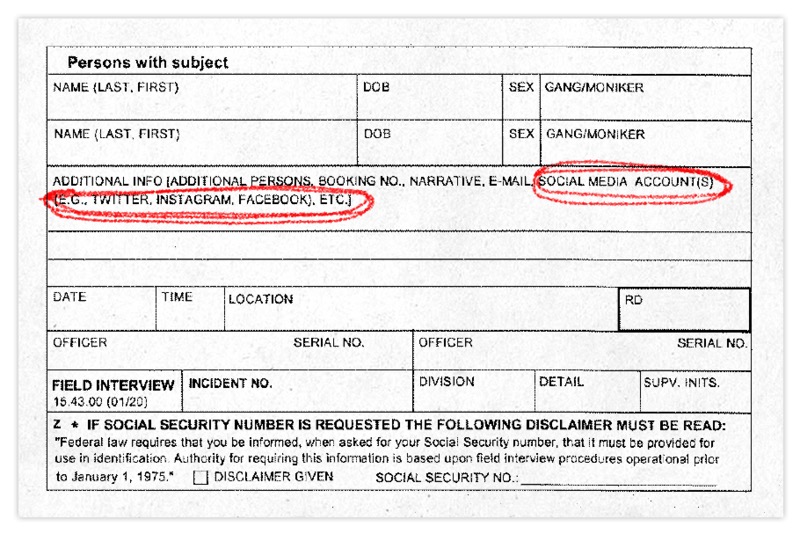

The Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) instructs officers to collect social media account information and email addresses when they interview people they have detained, according to documents obtained by the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law.

The Brennan Center filed public records requests with LAPD and police departments from other major cities, finding among other things that “the LAPD instructs its officers to broadly collect social media account information from those they encounter in person using field interview (FI) card.” The LAPD initially resisted making documents available but supplied over 6,000 pages after the Brennan Center sued the department.

One such document, a memo from then-LAPD Chief Charlie Beck in May 2015, said that “When completing a FI report, officers should ask for a person’s social media and e-mail account information and include it in the ‘Additional Info’ box.” That includes Twitter, Instagram, or Facebook profiles, the memo said.

This may be an unusual policy even though the LAPD has been doing it for years. “Apparently, nothing bars officers from filling out FI cards for each interaction they engage in on patrol,” wrote Mary Pat Dwyer, a lawyer and fellow in the Brennan Center’s Liberty and National Security Program. “Notably, our review of information about FI cards in 40 other cities did not reveal any other police departments that use the cards to collect social media data, though details are sparse.” The center reviewed “publicly available documents to try to determine if other police departments routinely collect social media during field interviews” but found that “most are not very transparent about their practices,” Dwyer told Ars today.

While people can refuse to give officers their social media account details, many people may not know their rights and could feel pressured into providing the information, Dwyer told Ars. “Courts have found that stopping individuals and asking for voluntary information doesn’t violate the Fourth Amendment and people are free not to respond,” she told us. “However, depending on the circumstances of a stop, people may not feel that freedom to walk away without responding. They may not know their rights, or they may be hoping to quickly end the encounter by providing information in order to ensure it doesn’t escalate.”

The Brennan Center has also been seeking police department records since January 2020 from Boston, New York City, Baltimore, and Washington, DC, but is still fighting to get all the requested information.

Data enables “large-scale monitoring”

A field interview is defined as “the brief detainment of an individual, whether on foot or in a vehicle, based on reasonable suspicion, for the purpose of determining the individual’s identity and resolving the officer’s suspicions concerning criminal activity,” according to an International Association of Chiefs of Police model policy for field interviews and pat-down searches. Field-interview cards can play a significant role in investigations.

“These cards facilitate large-scale monitoring of both the individuals on whom they are collected and their friends, family, and associates—even people suspected of no crime at all,” Dwyer wrote. “Information from the cards is fed into Palantir, a system through which the LAPD aggregates data from a wide array of sources to increase its surveillance and analytical capabilities.”

Officers apparently have wide discretion in choosing which people they record information on and, in some cases, have falsified the inputted information. Last year, the Los Angeles Times found that an LAPD “division under scrutiny for officers who allegedly falsified field interview cards that portrayed people as gang members has played an outsized role in the production of those cards.” The LAPD’s “Metropolitan Division made up about 4 percent of the force but accounted for more than 20 percent of the department’s field interview cards issued during a recent 18-month period,” the Times wrote. Police officers can fill out these cards “to document encounters they have with anyone they question on their beat,” the report also said.

It isn’t clear how much social media account information LAPD officers have collected or what officers do when people decline to provide the details. We contacted an LAPD spokesperson today and will update this article if we get a response. According to an article published by The Guardian, an LAPD spokesperson said that “the field interview card policy was ‘being updated,’ but declined to provide further details.”

LAPD expands social media monitoring

Collecting social media details during field interviews is one of a growing number of components in the LAPD’s use of social media for investigations. The Brennan Center said its public-records request found that LAPD “authorizes its officers to engage in extensive surveillance of social media without internal monitoring of the nature or effectiveness of the searches” and that, “beginning this year, the department is adding a new social media surveillance tool: Media Sonar, which can build detailed profiles on individuals and identify links between them. This acquisition increases opportunities for abuse by expanding officers’ ability to conduct wide-ranging social media surveillance.”

Media Sonar advertises that its products give investigators access to a “full digital snapshot of an individual’s online presence including all related personas and connections.”

The LAPD’s social media user guide encourages officers to monitor social media but imposes few restrictions on the practice, Dwyer wrote. The guide encourages officers to use “fictitious online personas” to conduct investigations and says that using these fake personas “does not constitute online undercover activity.”

“Few limitations offset this broad authority: officers need not document the searches they conduct, their purpose, or the justification,” she wrote. “They are not required to seek supervisory approval, and the guide offers no standards for the types of cases that warrant social media surveillance. While officers are instructed not to conduct social media surveillance for personal, illicit, or illegal purposes, they seem otherwise to have complete discretion over whom to surveil, how broadly to track their online activity, and how long to monitor them.”

The LAPD told the Brennan Center that it does not track what its employees monitor on social media sites and “has not conducted any audits regarding the use of social media.”

Broad authority, few restrictions

Dwyer argued that the expanding use of social media monitoring is particularly troubling at the LAPD because it has “identif[ied] people as gang members based on false or tenuous evidence” and “has a history of monitoring minority and activist communities.” Another detail revealed by the Brennan Center’s public-records request is that the LAPD used Geofeedia, a third-party vendor, “to search social media for information about Black Lives Matter activists and protests against police violence, using numerous hashtags to identify their posts,” Dwyer wrote. That was before Facebook and Twitter cut off Geofeedia’s access to social media data in 2016.

“Law enforcement should not have a free pass to broadly trawl the Internet without accountability or oversight,” Dwyer wrote. “Communities in Los Angeles and elsewhere must demand transparency in and limits around social media monitoring practices.”

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1793296