Ovid’s Metamorphoses speaks of the orb-weavers, said to be descendants of Arachne, a figure in Greek mythology who wove beautiful tapestries and dared to challenge Athena to a weaving contest. Angry that she could find no flaws with Arachne’s work—and also because the tapestry depicted the gods in an unflattering light—Athena beat the girl with a shuttle. When Arachne hanged herself in remorse, Athena took pity and transformed the rope into a web and Arachne into a spider.

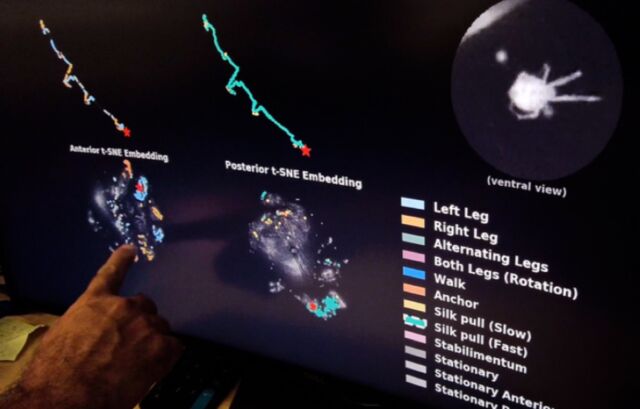

It’s an apt literary allusion for a new study on how spiders weave their webs, which is no doubt why scientists at Johns Hopkins University referenced the Ovid story in a recent paper published in the journal Current Biology. The JHU team used night vision and AI to record every single movement of several hackled orb-weavers as they spun their webs. The experiment revealed that the spiders rely on a shared set of movements amounting to “a web-building playbook or algorithm” to create the elegant, geometrically precise structures—even though they have teeny-tiny brains compared to humans.

Co-author Andrew Gordus, a behavioral biologist at JHU, said that he was inspired to undertake the project while he was out birding with his son and saw an especially spectacular spider web. “I thought, ‘If you went to a zoo and saw a chimpanzee building this, you’d think that’s one amazing and impressive chimpanzee,'” said Gordus. “Well, this is even more amazing because a spider’s brain is so tiny and I was frustrated that we didn’t know more about how this remarkable behavior occurs. Now we’ve defined the entire choreography for web building, which has never been done for any animal architecture at this fine of a resolution.”

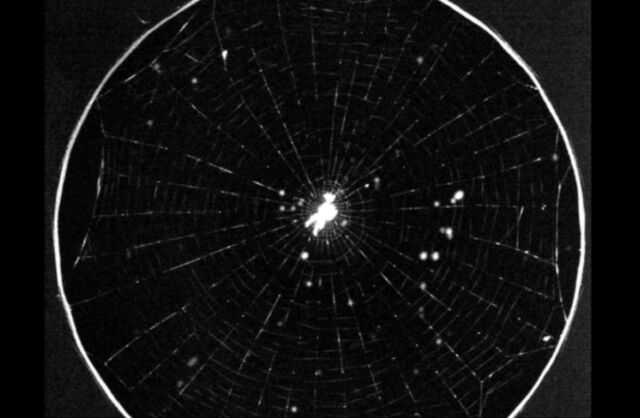

In addition to being aesthetically striking wonders of nature, spider webs constitute a kind of physical record for many aspects of a spider’s behavior, according to the authors. Gordus and his colleagues thought that they could quantify orb-weaving behavior, since the process of building a web can be easily defined both by a spider’s trajectory and the geometry of the web.

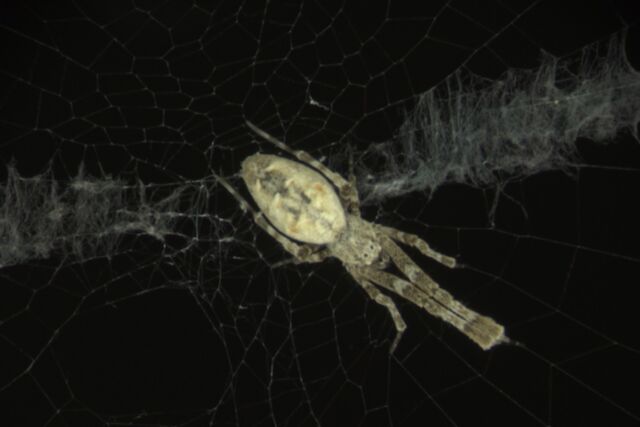

There are many different species of orb-weaving spiders, but the JHU team chose to work with Uloborus diversus. The team picked U. diversus because it remains active throughout the year and is also conveniently small. Specimens were collected in Half Moon Bay, California, and housed in an on-campus greenhouse. There, the spiders dined on fruit flies once a week. Only adult female spiders were used, since adult males rarely build webs.

For the actual experiments, the team designed a plexiglass arena in the lab, coated with paper at the edges to encourage web-building, and outfitted with infrared cameras and infrared lights. (U. diversus is a nocturnal spider, with a preference for building horizontal webs in the dark.) Then the researchers transferred six spiders to the arena and recorded the spiders every night as they wove their webs for an average of 24 hours.

This activity usually followed a well-defined progression. The spider starts by exploring the space before building a protoweb that will not be part of the final structure. Think of an artist producing a rough preliminary sketch. The protowebs are fairly disorganized, and there are long irregular pauses in the spider’s activity as it builds its protoweb—sometimes as long as eight hours, because you can’t rush inspiration.

“It is thought that this state of web-building is an exploratory phase in which the spider assesses the structural integrity of its surroundings and locates anchor points for the final web,” the authors wrote.

Next, the spider moves on to constructing the radii and frame for the web. “The construction of the frame is often the result of anchoring silk on the periphery before the return, and then walking outward along a prior radius, anchoring the frame silk at the end of the line, and then returning to the hub,” the authors wrote.

Once the radii and frame are in place, the spider moves on to constructing an auxiliary spiral, which takes just a few minutes. Scientists think this stage helps stabilize the structure before the spider builds the final capture spiral, since the auxiliary spiral is temporary. The spider usually takes the auxiliary spiral down once the full web is complete. Once the capture spiral is done, the spider hunkers down at the hub, sometimes for several days, patiently waiting for prey to get trapped in its web.

The researchers were able to track millions of individual leg movements by designing their own machine-vision software for that purpose. “Even if you video record it, that’s a lot of legs to track, over a long time, across many individuals,” said co-author Abel Corver, a graduate student studying web-making and neurophysiology. “It’s just too much to go through every frame and annotate the leg points by hand so we trained machine vision software to detect the posture of the spider, frame by frame, so we could document everything the legs do to build an entire web.”

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1811012