Several years ago, staffers at Estero Llano Grande State Park in Weslaco, Texas, noticed a new type of invasive ant species. Tawny crazy ants were so aggressive that they were driving birds out of their nests and occasionally swarming over visitors who paused to sit on a trail. Populations of other native species—like scorpions, snakes, tarantulas, and lizards—sharply declined, while rabbits were blinded by the ants’ venom.

That’s when University of Texas at Austin biologist Ed LeBrun got involved. The park “had a crazy ant infestation, and it was apocalyptic—rivers of ants going up and down every tree,” he said. Crazy ants have since spread rapidly through every state on the Gulf Coast, with over 27 Texas counties reporting significant infestations. The usual ant-bait traps and over-the-counter pesticides have proven ineffective, so the EPA has approved the temporary (but restricted) use of an anti-termite agent called fipronil. But a more targeted and less toxic control strategy would be better.

LeBrun has worked extensively on fire ants, another invasive species that has plagued the region. He has spent the last few years investigating potential sustainable control strategies based on crazy ants’ natural enemies in the wild. LeBrun and his colleagues have now discovered that a specific type of fungus can effectively wipe out crazy ant colonies while leaving other native species alone, according to a new paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Originally hailing from South America, tawny crazy ants (Nylanderia fulva) get their name because of their unpredictable movements. (They are also sometimes known as Rasberry crazy ants after exterminator Tom Rasberry.) The ants are unusual because they don’t build central mounds or nests. Instead, colonies make their homes under stones, in rotting logs, or in any kind of pre-existing hole in the ground. Crazy ant colonies also have multiple queens, which contributes to their hardiness.

For some reason, crazy ants are attracted to electrical equipment. They can even chew through insulation and wiring and short out electrical equipment. A swarm of crazy ants can asphyxiate a chicken, and swarms have been known to attack larger animals, like cattle, around the eyes, nostrils, and hooves. Some homeowners in the Lone Star State were sweeping up dustpans full of dead crazy ants on a daily basis at the height of infestation.

Crazy ants don’t have the painful bite of fire ants, but they do excrete formic acid they can use as a venom—hence the blinded rabbits in Estero Llano Grande State Park. In 2014, scientists discovered that crazy ants could survive exposure to fire ant venom 98 percent of the time by using their own formic acid to detoxify the venom. When their gland ducts were blocked, crazy ants had only a 48 percent survival rate.

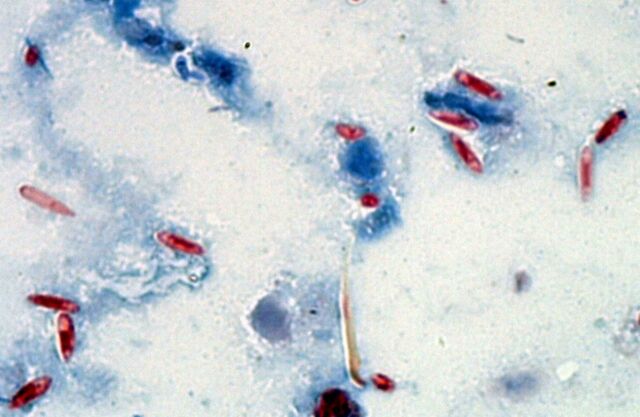

A useful clue for fighting off this invasive species came from other research LeBrun had conducted with Rob Plowes of Brackenridge Field Laboratory on a population of crazy ants collected in Florida. Several of the ants had swollen abdomens. LeBrun and Plowes found that those bodies contained spores of a parasite from the fungal microsporidian group. The researchers had seen similar symptoms in fire ants infected with other kinds of microsporidia, which hijack an ant’s fat cells to produce even more spores. But the type of microsporidium affecting the crazy ants was an entirely new genus, suggesting it might infect crazy ants but leave other species alone.

This was the first dent in the crazy ants’ armor LeBrun had been able to find. Since then, he and his co-authors have been diligently studying this new type of microsporidia—dubbed M. nylanderiae—to learn more about how it infects and spreads throughout an ant colony. The researchers focused on 15 particular crazy ant colonies in Texas and monitored the colonies over eight years for signs of infection.

The scientists found that every infected crazy ant population declined substantially, usually over the winter, and 62 percent of the populations were wiped out entirely. That’s unusual, per LeBrun, since there is usually a “boom and bust cycle” associated with the spread of pathogens. The authors suggest that the collapses occurred in part because of the shortened life spans of worker ants, making it harder for the colonies to gather enough resources to survive winters.

Next, LeBrun et al. collected infected crazy ants from other regions and placed them in nest boxes near two other uninfected sites. The researchers used hot dogs as bait around the exits to get the two populations to merge. The result: Infection levels rose exponentially at both those sites.

Today, Estero Llano Grande State Park is refreshingly free of crazy ant infestations, and native species have started to return to the area. A crazy ant infestation was also eradicated at a second site, according to LeBrun, and he and his team plan to expand their new biocontrol method to other Texas habitats plagued by crazy ant infections this spring.

“I think it has a lot of potential for the protection of sensitive habitats with endangered species or areas of high conservation value,” LeBrun said. “This doesn’t mean crazy ants will disappear. It’s impossible to predict how long it will take for the lightning bolt to strike and the pathogen to infect any one crazy ant population. But it’s a big relief because it means these populations appear to have a life span.”

DOI: PNAS, 2022. 10.1073/pnas.2114558119 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1843835